Did vaccines after 1953 reduce childhood mortality?

Not much, or at all (besides, again, polio)

This post is the sequel to the examination of childhood mortality in 1951-1953, the years immediately before the Salk polio vaccine, and the introductory exploration of reductions 50 years later.

Finally, we ask:

Infectious disease deaths among children were already rare in 1953 (about half as common as deaths from accidents). With only an (at best) limited role for the few vaccines introduced before 1953 in previous reductions, did the ones introduced afterward make any further difference?

“Where are the receipts (besides for polio)?”

The simplest approach is to be specific. What childhood mortality reductions took place between 1953 and 2003, and did these correspond to prior or new vaccines? Afterward, we will examine some more wholistic arguments.

As previously caveated to death, evidence is strong that the polio vaccines reduced polio mortality and associated paralytic epidemics.1 No serious examination of the topic of vaccines and childhood mortality is possible without acknowledging this point; and producing an examination of the topic that doesn’t get the polio part of the story so completely wrong is essentially the entire purpose of this work.

Polio was a substantial driver of childhood mortality in 1951 - 1953, though still ranking behind tuberculosis or pneumonia. In fact, these years were all-time records for the number of recorded cases and among the worst years for per-capital mortality, despite substantial improvements in averting death in the case of respiratory paralysis followed by recovery. This unnatural worsening — when other disease mortality was declining across the board — resulted, again, from the fact that polio was not a truly “natural” disease.2

Therefore when we “open the box” of mortality reductions after 1953, we expect to see polio and expect to count this as a reduction owed to a vaccine; what we are interested in is the negative space — do vaccines account for any or much of all the other reductions which took place?

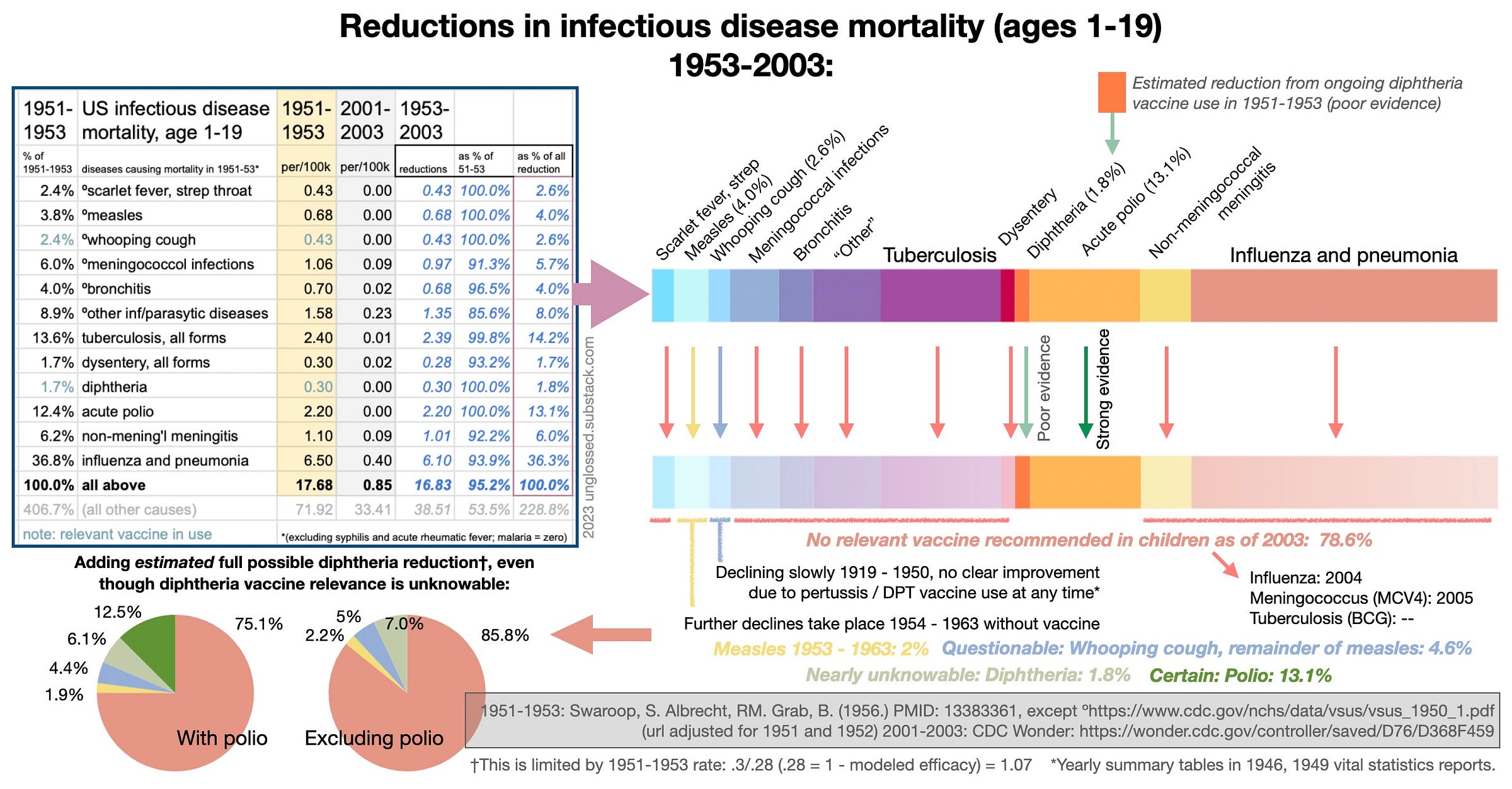

It was difficult to settle on any one approach to visualizing the specific case. Ultimately, I plotted all the reductions by disease type into a big, dumb bar, so that the proportion of reductions that took place without vaccines and the relevant quality of evidence regarding those that took place with vaccines could be visualized.

Save for polio, nearly the entirety of childhood infectious disease mortality reductions after 1953 occurred without the availability or recommendation of a relevant vaccine. For the handful of diseases with relevant vaccines, it is far from obvious that those same vaccines “caused” the respective declines, given that no vaccines were required for reducing or eliminating mortality from the other diseases.

Really quantifying the hypothetical relevance of vaccines is, however, made quite difficult by the fact that two of our relevant but questionable vaccines are already in use in 1951 - 1953: diphtheria and pertussis (for whooping cough).

It was largely for this reason that I was driven to rework from scratch the all-ages mortality declines for a wide gamut of diseases from 1900-1950, so that there would at least be some evidence and math to back up any predictions made in this post.

This led to even more confidence that whooping cough rates in 1951 - 1953 were not credibly influenced by ongoing vaccination. It led, meanwhile, to an un-confident case that diphtheria vaccines may have influenced ongoing rates, and a method for modeling the potential (but ultimately unknowable) effect. This method was described in an update to the previous post in this series. To emphasize — the effect of the diphtheria vaccine could scarcely be more unknowable than it is, as not only was it widely used without a controlled trial, but background mortality rates were already influenced to an unknowable extent by antitoxin. At all events the final formula is simple (observed rate / .28), and bounds the possible “ongoing reduction” in diphtheria deaths to the rate of deaths actually observed in 1951 - 1953.

Adding the hypothetical “ongoing diphtheria reduction” results in the pie charts at the bottom left, in which the role of vaccines in ongoing and further reductions are either:

obviously impossible (no vaccine or measles reductions before 1963) (77%)

questionable (whooping cough and the 1963 measles rate) (4.4%)

unknowable (diphtheria, with hypothetical extra deaths) (6.1%)

polio (12.5%)

With polio removed on the grounds of being “an exception that describes the rules,” obviously impossible raises to 88.1% (again, this with extra prevented deaths added in for diphtheria as a total hypothetical).

The wholistic cases that vaccines were of limited relevance

i. The other infectious diseases

Childhood (aged 1 to 19) mortality declines greatly for infectious diseases that had no relevant vaccines. It is therefore unreasonable, absent exceptional evidence, to suppose that vaccines were required for the reductions that took place for diphtheria, pertussis, and measles after 1953. This is especially true given that measles mortality experienced a further 50% decline in the ensuing ten years, before the first vaccine was licensed.

Case study: Meningococcus

Childhood mortality attributed to meningococcus infections declined by 91.3% between 1953 and 2003.

The CDC is fully transparent that this decline had nothing to do with the vaccines eventually licensed for meningococcus:

Incidence of meningococcal disease has declined in the United States since the 1990s and remains low today. Much [i.e. almost all] of the decline occurred prior to routine use of MenACWY vaccines [after 2005]. In addition, serogroup B meningococcal disease declined even though MenB vaccines were not available until the end of 2014.

Meningococcal vaccines were, in other words, “solutions” chasing a problem that had already solved itself.

Case study: Influenza and pneumonia

Likewise, childhood mortality from influenza and pneumonia declined from 1951 - 1953 rates without substantial use of influenza vaccines in children.

This is not surprising — here, antibiotics and improved access to medical care3 should have been expected to reduce almost all deaths.

Once again, the relevant vaccine — i.e. the flu vaccine, absurdly recommended for children starting in 2004 — was a solution chasing a problem that had already solved itself.

ii. The other age groups

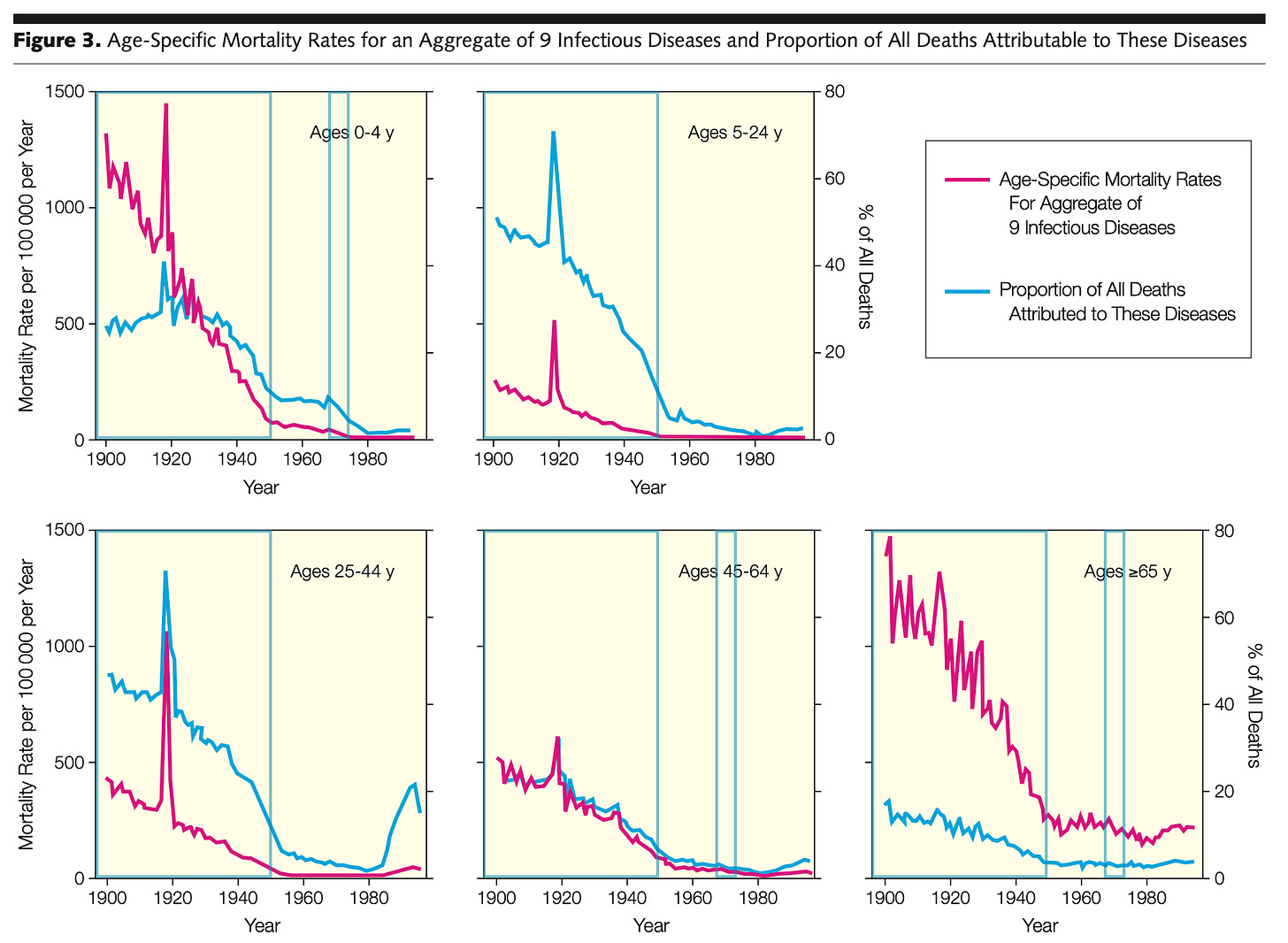

Infectious disease deaths (except for polio) had been declining in all age groups before 1953; they subsequently leveled in all age groups (in two groups they had basically reached zero).

Further declines in ages 0-4 take place after the late 1960s, which coincides with the trends in both of the two older adult groups still experiencing notable rates. Thus, at no point in time are childhood deaths reduced without a parallel development in all or some other age groups, which suggests that external factors unrelated to childhood vaccines drove the reductions at all points.

If only children were for the most part being vaccinated4, vaccines before 1953 were obviously not driving the reduction in all age groups, and vaccines after 1953 were not driving the reduction in the 45-64 year-old group.

In the case of tuberculosis the reverse is more likely, and reductions in older groups after 1945 drove reductions in children. While streptomycin proved incapable of curing tuberculosis by itself, it sparked a new age in which tuberculosis was considered solvable, rather than something to merely be endured. The ensuing identification and curing of adult tuberculosis cases with radiography, skin tests, and broad spectrum antibiotics gradually eliminated the primary exposure risk for individual children. By 1980, new tuberculosis cases throughout the West were only reported in 1 out of 10,000 people annually.5 If kids (and other adults) do not live with actively6 infected adults, they are unlikely to become active cases themselves.

(Regarding the BCG vaccine, it is appropriate to mention that my previous comments on this topic incorrectly suggested that there was significant use among American children at some point after the mid-1940s field trials. This does not seem to have ever taken place.7)

In general, “something” reduced infectious disease deaths in all age groups in the 20th Century. In older groups that something was not vaccines. Therefore, it was more likely standard of living improvements after 1914, reductions in tuberculosis, and advances in curative medicine, including the advent of antibiotics, beginning some time in the 1930s — and there is no reason these improvements should have failed to exert the same benefits in young children.

iii. The non-infectious diseases

Hence, we can also compare infectious disease reductions with reductions for other diseases. Here it is clear that deaths from cancer and congenital disease were reduced by 2/3 after 1953.

These diseases are largely indifferent to our other external factors (i.e. standard-of-living), and so were probably improved by medical advances.8

If curative medicine could reduce mortality from cancer and congenital conditions by 67%, certainly it could do better for infectious diseases, given the substantial efficacy of antibiotics.

It is therefore reasonable to presume — again absent extraordinary evidence otherwise — that vaccines had little role in the reduction of whooping cough and measles mortality. Diphtheria is an unknowable — a sensible modern approach would probably be to stop vaccinating for diphtheria and monitor the results.9

The standard of extraordinary evidence only exists for polio, which was both already treated to the practical limits of curative medicine in 1951 - 1953, and radically reduced immediately upon the widespread use of either of the vaccines (again, I would endorse only the Sabin vaccine for long-term use).

If you derived value from this post, please drop a few coins in your fact-barista’s tip jar.

It is not the purpose of this post to litigate the case for the polio vaccines. It suffices to refer to the segment on polio in the following paper, which can be contrasted (dramatically) with the poor quality of evidence supporting the importance of the other vaccines reviewed:

Karzon, DT. (1969.) “Immunization practice in the United States and Great Britain: a comparative study.” Postgrad Med J. 1969 Feb; 45(520): 147–160.

See, once again, Explaining Polio.

As before, “access” in the context of children largely consists of having symptoms noticed and replied to before the late stages of disease.

Aside from in the military, and to some extent the elderly (over 65) in the case of the flu vaccines. The latter is of no obvious relevance since infectious disease deaths no longer decline in this group after the 1950s.

A figure given in Max Perutz’s review of Frank Ryan’s “The Forgotten Plague.”

Max Perutz. p 175. “I Wish I’d Made You Angry Earlier,” 2003 edition. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press.

As opposed to latently, which is not a big risk factor except in an immune-deficient condition.

Scandinavian countries embraced the BCG vaccine in 1939, after the pause which followed the Lübeck disaster. BCG campaigns took place in Europe and Japan under the guise of war recovery. Local health authorities in the United Kingdom and Canada seem to have run screening and vaccination campaigns, though as with other vaccines, there was reticence in England. In the United States, as of 1957, it is only being used in “certain select groups.” Described in:

Stan Fellers. “Doctors Disagree on Use of BCG Vaccine in Tuberculosis.” Fort Collins Coloradoan. December 2, 1957. newspapers.com

Appendicitis is an interesting case, as besides advances in treatment, rates of incidence mysteriously declined. See:

Addiss, DG. Shaffer, N. Fowler, BS. Tauxe, RV. (1990.) “The epidemiology of appendicitis and appendectomy in the United States.” Am J Epidemiol. 1990 Nov;132(5):910-25.

Between 1970 and 1984, the incidence of appendicitis decreased by 14.6%; reasons for this decline are unknown.

Bearing in mind that the disease only rose to prominence after the urbanization of the West (see “Diphtheria: The Forgotten Mystery”). It may be the case that population density (of children) still favors virulent strains of diphtheria. There is no reason, however, to simply assume that it does.

Many readers are clearly enamored of this memetic notion that somehow polio was just 'reclassified' out of existence. The toxin theory meme. You come across a post that is about *all diseases except polio, did vaccines reduce deaths for these (no)?* and your only reaction is "polio just reclassified."

It needs to be emphasized just how badly stupid and implausible the claim is. American newspapers never depended on medical, laboratory, or statistical confirmation to report polio epidemics.

I am poking a cult. You have come across some suggestion of a "secret knowledge" that makes you one of the "awake." This is just astrology but with pesticides as your star signs. You aren't being serious. I say why would a neurotoxin not first deteriorate higher order functions - personality, cognition, vision - how could it magically just go for the motor neurons? Why wouldn't adults be more affected after years of chronic exposure to your magic pesticide star signs? Not even crickets. You don't even care about the truth, just the feeling that you get from this magic thinking about your secret "knowledge." Look, you have found someone else who also has this "knowledge" now that you scrolled below the comment you just posted (which said the same thing as them). Wait, you keep scrolling, here is another person with the secret knowledge. (Incredible, what you can learn when you read the previous comments instead of just blasting off your own copy of the meme.) Wow what a lot of you to know a "secret"! It is just a meme that has taken over your brains.

My daughter got whooping cough a few weeks after her whooping cough vaccine back in the early 90s.

She was only a couple of months old and the majority of her care was done at home by myself, while she struggled to breathe, turning grey many times. We went to the dr almost daily and were told it was just a cold. The Dr said my descriptions of her illness sounded exactly like whooping cough, but that was silly and also impossible, as whooping cough didnt even exist any more.

I knew my child was ill but had no help from her doctors, so I traveled quite a distance to the dr who was my childhood pediatrician. He chose not to scare me, but told my mother that he knew immediately on exam, that my daughter had whooping cough, but he just told me, best to bring her in to the hospital, where of course, per his call ahead, she was immediately admitted and put into an oxygen tent with her o2 readings dipping into the 60s at times. I asked him later if the shot could have caused her whooping cough...he never did answer that one.

She recovered quickly, as I was a strong willed young mom who'd been taking care of her whooping cough at home for weeks already, and disregarded a lot of invasive hospital advice, as I'd already found ways to treat the issues (much better than the hospital seemed able to too).

After about a week in the oxygen tent, I brought her home and she recovered well.

Our whooping cough vaccines did NOT stop the rest of the family from getting whooping cough...and it's not something you die from. Not a fun illness at all, but with a little knowledge, very survivable, even for a small infant.

I think most, if not all illness, are more fairy tale boogie man than anything else.

Young people today are 100% sure that chicken pox is a deadly disease. It's all so laughable, yet very sad and concerning, how ignorance has been manipulated into fear and existential anxiety.