299 of 300: Infectious disease in childhood in the 1950s

Another way of challenging the illusion that vaccines are necessary.

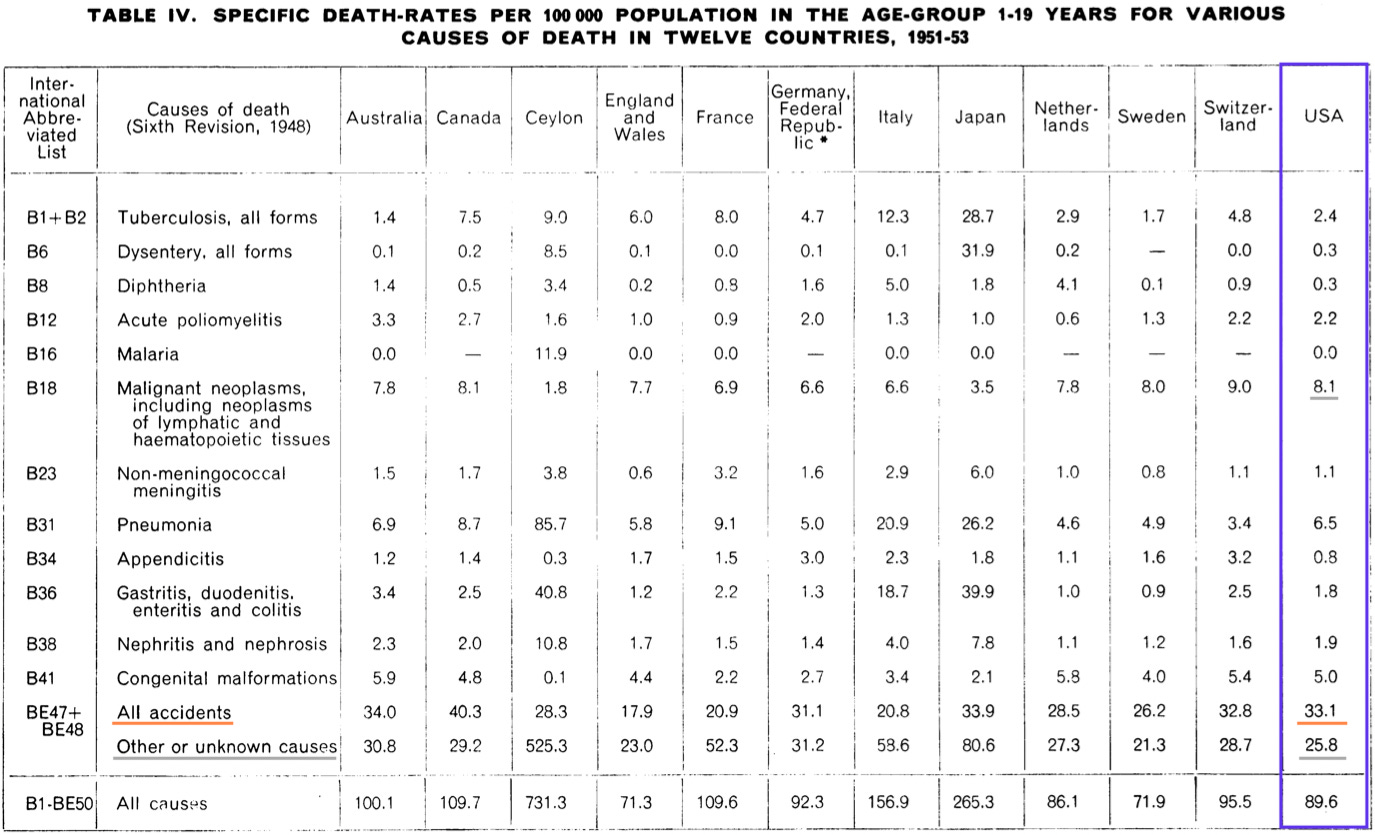

This post summarizes the state of childhood mortality (ages 1 to 19) in 1951 - 1953, immediately before the polio vaccines. A follow-up post will offer a comparison to mortality in 2001 - 2003, immediately before flu vaccines were recommended for children, as well as further analysis of the likely roll of vaccines in mortality reductions before and after 1953.

The rise of accidents

In 1948 the World Health Organization was formed, only to discover that the “world” was… already healthy.

Or at least, the developed nations — in these, new and standardized medical classifications were put in place after 1948, to get an idea of what people were dying of and presumably justify all manner of public-health meddling in the affairs of wealthy nations. And yet it immediately turned out that for children in these nations, the single largest cause of deaths was not disease, not infection, not starvation — but accidents.

This revelation resulted in the paper sampled above.1

The leading cause of death

The paper sampled above has inspired this post, and was encountered as a result of a discussion with a belligerent and misinformed neighbor.

I had just described to said neighbor the interesting fact that around 1950, polio was only the 24th leading cause of death in American children. What was the first cause? demanded the neighbor, apparently dimly imagining that it would turn out to be (I don’t know) “mega polio” or something of the sort.

Off the top of my head, I did not know, but after much berating, I guessed that the leading cause of death around 1950 was probably accidents. Confirming this intuition after the conversation led me to the paper above, and to further explorations of mortality statistics in 1951 - 1953; in short, I was correct. The transition to accidents as the number one cause of death for American children had in fact occurred nearly a decade earlier.

But Swaroop, et al. not only confirmed I was right about the top cause of death, but displayed the landscape of childhood mortality in a manner which was (as already described) inspiring in its simplicity. Behold, mortality in 1951-1953:

From this, it would appear that accidents are the leading cause of death in children, followed by “other,” followed by all infections together, followed by cancer. Below it will become clear that “other” includes some additional infectious disease deaths; but the overall trend is unchanged. (I wanted to first provide the original presentation from the 1956 paper, as I felt all my supplemental information, though necessary for the most accurate picture, ultimately distracts from the clear view provided above.)

This post serves to validate and explore these simple figures, to reinforce a realistic picture of the (supposed) role of vaccines in modern pediatric health.

A realistic picture of childhood mortality before most vaccines

The following is compiled from the WHO paper, which reports rates for 1951-1953, and CDC Vital statistics reports for 1950-19522 for select causes left out from the same paper (namely, infectious diseases with lower rates of death). It is openly acknowledged that three relevant vaccines are already in use; still, this provides an extremely useful reference point for appreciating the baby boomer-era reality of childhood mortality:

Immediate notes:

Obviously, infant and maternal mortality are left out of this picture. This is entirely appropriate since the ultimate perspective will be on vaccines, which have at best a marginal role in infections occurring before age 1. In short, who cares about babies — do any kids need vaccines?

By 1951-1953, penicillin and streptomycin are now widely available and in substantial use. Additionally, as noted, vaccines are and have been in use for a handful of infectious diseases (but not yet polio until 1955, nor measles for another decade).

No single rate is accurate for either whites or Blacks, nor really any individual in any circumstance. However, as seen above, the combined rate is mostly an accurate picture for whites overall (89.3 vs. 82.0 deaths), and probably a good proxy for medium-to-lower-income whites. This is sufficient to disregard racial breakdowns for now, and consider the “American child” as a unit (though one that is simultaneously not representative of Black children).

For consistency, statistics for 2001-2003 below and in the follow-up post will be limited to whites and Blacks combined.

As can be seen, accidents cause 37% of deaths in American children, a larger contributor than any other single cause, and larger than all infectious diseases put together. The same, infectious diseases attributed as such, are comparable in deaths to congenital conditions and cancer put together (20% and 15%, respectively), and this leaves out cardiovascular deaths.

299 in 300 children did not need any more vaccines in 1953

(Aside of course from the polio vaccines.)

From the above, it is clear that only 1 out of 5,650 American children aged 1 - 19 died annually as a direct result of an infectious disease in the years just before the polio vaccine. A good portion of these deaths were from pneumonia, which had largely become treatable thanks to antibiotics, and isn’t particularly relevant to future vaccines. Meanwhile, I have excluded deaths attributed to abdominal inflammation, as a separate category existed for dysentery (i.e. diarrhea) and is included in infectious deaths accordingly. These and other relevant considerations will be further discussed in the follow-up to this post.

Thus to produce the most “generous” possible interpretation of the “danger” of infectious diseases in 1951-1953, the annual rate for ages 1 - 19 should be multiplied by 19, leaving in pneumonia, despite pneumonia deaths likely reflecting lack of access to nutrition and care. This would tell us that only 1 out of 297 children who reach age 1 will die of an infectious disease before age 20 at the “going rates” — i.e., had no improvement in outcomes occurred after 1953. This may forgivably be rounded to 1 in 300.

Chances were twice as high for dying of an accident of some type — 1 in 3,021 yearly, and 1 in 159 by age 20.

With infectious diseases only half as likely to kill children as random accidents, pediatric public health in 1953 was obviously “just fine” but for the exception of tuberculosis and polio. Further pediatric health improvements beyond those two diseases ought to have taken less priority than, for example, swimming instruction, or automobile design — and did not demand bothering the 299 out of 300 children who would not die from infectious disease with any novel, preemptive injections. Such unneeded medical interventions are no more reasonable than locking 100% of children in foam-padded rooms until age 20, to protect the unknown handful who might break a bone every day.

Thus, every future vaccine but for polio may be damned immediately as intrusive and excessive — frankly, as idiotic meddling upon the already healthy 299 — before we even consider whether said vaccines really contributed more than improvements to medical treatment.

Our two exceptions

Tuberculosis for its part was the major killer of children among infectious diseases (likely contributing to pneumonia deaths as well), but the risk of tuberculosis to children vanishes once adult cases are brought under control. This was effected in the three decades after the advent of streptomycin, with more aggressive and confident screening and isolation of active cases helping to control spread further. The BCG vaccine was never (to the best of my historical reconstruction) substantially used in the American tuberculosis elimination effort.3

As for polio, the oral vaccine eventually used after 1960 is an excellent product, that provides children with robust mucosal immunity and indirectly “boosts” the immunity of the population as a whole. The OPV can almost be considered less a “vaccine” than a “domesticated polio virus” which is encouraged to run free in children. At all events, because polio deaths drastically underrepresented permanent harm from polio infections in 1951-1953 (due to well-funded treatment4), and because rates of paralytic disease likely would have continued to increase due to other injections,5 polio vaccines in general can be seen as a “necessity” of modern life. The inactivated vaccine and its associated fantasy of “eradication” is likely a poor long-term solution for this necessity; the OPV is best from a pragmatic standpoint.

Next: 50 years of progress(?): Reductions, 2001 - 2003

The raw data for the above graph is in the following table, which segues to an examination of which deaths were subsequently reduced. Table:

This data will be discussed in the next post, but is included here to provide sourcing for the previous graph.

If you derived value from this post, please drop a few coins in your fact-barista’s tip jar.

Swaroop, S. Albrecht, RM. Grab, B. (1956.) “Accident mortality among children.” Bull World Health Organ. 1956; 15(1-2): 123–163.

These are simply parked online in pdf form, though I never would have found them through the CDC interface. 1953 does not load, hence the use of 1950:

https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/vsus/vsus_1950_1.pdf

My original comments on this topic incorrectly suggested that there was significant use among American children at some point after the mid-1940s field trials. This does not seem to have ever taken place.

Scandinavian countries embraced the BCG vaccine in 1939, after the pause which followed the Lübeck disaster. Later BCG campaigns took place in Europe and Japan under the guise of war recovery. Local health authorities in the United Kingdom and Canada seem to have run screening and vaccination campaigns, though as with other vaccines, there was reticence in England. In the United States, as of 1957, it was only being used in “certain select groups.” Described in:

Stan Fellers. “Doctors Disagree on Use of BCG Vaccine in Tuberculosis.” Fort Collins Coloradoan. December 2, 1957. newspapers.com

Hence, in the US there were 7.6 paralytic cases recorded for every 1 death between 1951 - 1953.

See Payne, AM-M. Freych, M-J. (1956.) “Poliomyelitis in 1954.” Bull World Health Organ. 1956; 15(1-2): 43–121.

See “Explaining Polio.”

Great post as always. Something that's interested me is whether we reeeally do need a second measles vaccine. Heres a chart showing UK cases before and after introduction of the measles vaccine, but also note that the second dose was introduced in 1996 despite cases already being at a low level:

https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Measles-and-the-importance-of-maintaining-levels.-Bedford/903044dd476ecbf5c5f128fd674013ed382148a4/figure/1

The same applies to Japan, who only introduced their second dose in 2006 (See Figure 1)

https://www.mdpi.com/1999-4915/15/1/171#fig_body_display_viruses-15-00171-f001

So is it a case of chasing diminishing returns to fulfil a policy objective of elimination?

The variation between the values for the various countries in that first table is something!