The risk of this is that by the time the 4th wave which is predicted to come somewhere around November, would be possibly driven by a new variant and it may find us still at the tail end of the third wave which would mean that the health facilities and workers would not have had much rest.

Joe Phaahla, South African Health Minister, August 27, 2021.1

After Tuesday’s post philosophizing against taking the mildness of Omicron for granted, I didn’t expect to address the subject again until a few more weeks had passed - any takes offered in advance of such an interval being unlikely to retain relevance once better data arrives. Still, as some of this weekend’s media-delivered Omicron developments are a bit curious and/or misleading, an excursion into the topical beckons. On the docket:

Scheduled Waves in South Africa!

Kids in the Hospital in South Africa!

Scheduled Waves in South Africa!

South Africans are evidently on edge over a fantastic overlap between current events and the predictions made by local public health experts months in advance. In a streamed interview with Inayet Wadee on December 1st, Public Health Specialist Waasila Jassat fields an attempt to ease local suspicions (emphasis added):

[Wadee] There are those who are still very very skeptical when these variants come out, and, uh, sometimes questions are raised, uh, as to how these variants can be predicted and uh, we know, that in May, already, we heard about a variant that will come out in, uh, December. And, uh, people are skeptical, saying that, you know, “How can this be predicted? And, uh, so in terms of, uh, variant after variant that we will possibly be experiencing going into the future, how much longer do we have to live with these variants?”[…]

[Jassat] Yeah, I mean, I’ve noticed throughout this pandemic, there’s a sense of mistrust and unease, you know, trusting the information that’s given to you. And I understand, you know, people are fatigued, as well, people are um, you know, skeptical about what they hear, and they’ve been fed a lot of misinformation. And so, yeah, when, when you see that someone predicts another wave and then that wave happens at the same time, you know, people are saying, “Oh, you know, it’s planned.” But really it’s the excellence of our epidemiologists in our country that have been doing a lot of hard work. Many of us have had not a day’s leave for, um, almost two years. So, you know, we’ve looked at the, sort of the experience of the other waves, we’ve looked at the size of the waves, the timing of the waves, and the timing between waves. It’s almost a certainty that new variants will emerge, that’s not something that’s hard to predict. It’s the nature of the virus. […] We knew it was highly likely that another wave would emerge at the end of the year, um, and, you know, it’s highly likely that, um, you know, variants would be behind that.3

Jassat doesn’t contradict Wadee’s reference to a prediction in May, nor does she blink an eye when the reference is uttered. But this may be due to the meandering nature of Wadee’s question. A more concrete record of official, early determination of the “schedule” for Omicron’s arrival appears in the summer, in such perfectly succinct form that the declaration was seemingly meant to be read in the future. On August 17, “Salim Abdool Karim, former chairman of the government’s ministerial advisory committee on Covid-19, told Bloomberg”:

Salim Abdool Karim, former chairman of the government’s ministerial advisory committee on Covid-19, told Bloomberg that the current estimates show the fourth wave starting on 2 December and will last about 75 days.

The government assumes that the wave will follow a similar pattern to the current one and that there will be a new variant by then […]4

(Three days off. They really “blew” that one.)

These incredibly prescient warnings - uttered, at the time, to encourage higher rates of vaccination - were repeated elsewhere in official discourse throughout the end of August, including the reference by Health Minister Joe Phaahla quoted at the top of this post. But it is the BUSINESSTECH report of Karim’s statement to Bloomberg that suggests a possible source, or “author” of the prediction (emphasis in original):

A report published by professional services firm PwC [PricewaterhouseCoopers] this week shows three scenarios for how South Africa’s lockdown levels could move until the end of the year.

Both PwC’s baseline and downside assumptions consider a likely fourth wave of infections starting around the December holidays.

But, this may have been mere coincidence; meaning that the South African public health hivemind came up with the December prediction on their own. Both sources may have been simply assuming a repeat of last year - even though, by August already, such a bet would have been rather bold (in fact, Phaahla’s statement on August 27 was partially in reply to the sudden upswing of cases at that time, raising fears that South Africa would enter into a prolonged wave as the UK went on to do.)

But was the government’s eventual presumption of a novel variant as a key driver of the December wave (“the 4th wave… would possibly driven by a new variant,” in Phaahla’s words), really “almost a certainty” (in Jassat’s words) - even back in August? Almost certainly not.

South Africa as of Omicron is on a winning streak when it comes to buzz-worthy “new releases” (metaphorically) of SARS-CoV-2, but does this truly speak to some local destiny? In the wake of “top virologist” Trevor Bedford’s infamous Telehealth Dissertation on increased mutation to the spike protein beginning at the end of last year, South Africa’s trial for AstraZeneca was implicated in the local arrival of Beta.5 But no such trials are being undertaken now; overall rates of Covid-vaccination are lower in South Africa than elsewhere; and no new variant arrived in the summer wave.

But in general, rates of “significant new variants per wave” in South Africa and elsewhere (via imported variants) are fairly close to 1; in fact it might have been more bold to predict that Delta would still be topping the local charts, this late in the year. The August South African expert consensus of a “December Variant,” therefor, was likely just one more banal, tossed-off invocation of “Boogeyspike,” intended to goad the local public into taking more useless pseudo-vaccine; not part of some overarching “schedule,” scripted by an international cabal, which plotted Omicron’s geographic emergence four months in advance. Hence why the PricewaterhouseCoopers report from August includes a literal schedule.

The reader can make of all this what they wish. But to suppose that there’s no great conspiracy behind The Pandemic™, at this point, directly supports the proposition that there must be at least a minor conspiracy, or array of conspiracies, to create belief in a great conspiracy behind The Pandemic™, by leaving obvious, fabricated “fingerprints” everywhere - including quite possibly in the past.6 Otherwise, one is left not only explaining away the grand movement as one giant coincidence, but all the kabuki of intentionality surrounding the movement as, somehow, a never-ending series of randomly generated illusions. Once, Americans looked up in the sky and saw box-cutters magically bring down passenger jets, but this was an aberration; now to look anywhere is to catch the “Build Back Better®️ Props Dept.” logo staring one in the face.7

Suppressing (rather than ignoring) this contradiction otherwise results in a great strain: There is no conspiracy; the only reason you think there is a conspiracy is because key actors keep displaying signs of a conspiracy by accident. It’s more plausible to acknowledge that “someone” wants there to be belief in a conspiracy, and has brought this desire into reality via conspiracy.8 But (ignoring or) suppressing the contradiction is the only route possible for those who, even in the current era, somehow still believe that conspiracy (targeting the citizenry at large) is itself “impossible.”

Yet in America, at least, we have myriad agencies and private consulting firms constructed for the explicit purpose of waging conspiracies in order to foster state interest; and in 2020 (false start) and 2021, just as in 2001, the state interest was declared to be controlling the behavior of the citizenry at large.

Still, this latest fingerprint, overtly suggesting an invisible hand at the tiller of Omicron, and authored by one of the American consulting firms dedicated to conspiracy,9 is surely too perfect. It must be an accident. Except, of course, that it is only one of several fingerprints plastered over our sensational new celebrity variant.

But supposing there is a grand conspiracy, at the moment, is no less inviting of contradictions. Is the formerly-liberal West meant to be driven into renewed emergency due to Omicron, or is this “suspiciously-constructed” variant some sort of “grand exit” from the entire project? Perhaps all options are on the table. Although the media purports to have loaded up the Omicron Scenario on Mild difficulty level, the array of assets flashing at the bottom of the screen are not all so reassuring.

One such hypothetically planted asset is the reinfections study; the other is the announcement of increased hospitalizations of children. Though I have carefully hedged my own bets on both the possibility and reality of Omicron in fact being “milder,”10 these two suspiciously early warning signs of “Omicron Hell Mode” are rather flimsy, and deserve to be provisionally dismissed.

Reinfections in South Africa!

(For correction notice on this segment, see footnotes.12)

Somehow even though Omicron is more or less three hours old, it has caused 35,670 reinfections in South Africa alone!

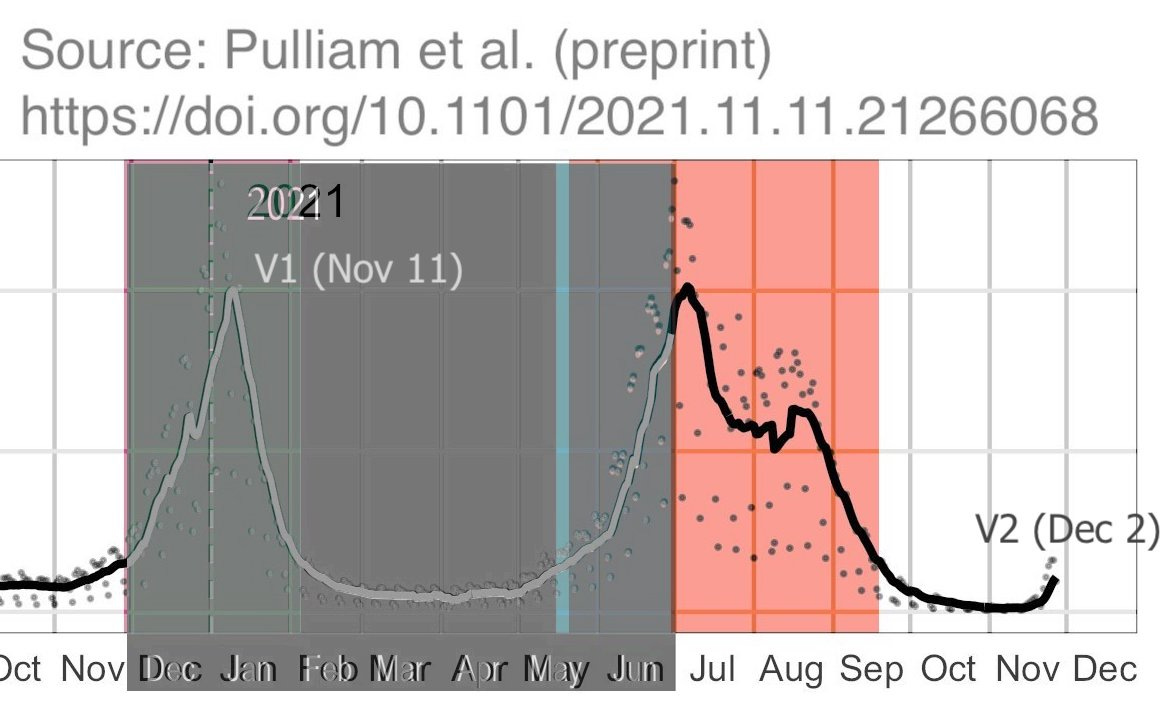

Or at least, that is the impression a reader would be forgiven for taking from the coverage surrounding the rush-delivered update to the pre-print by Pulliam, J. et al. “Increased risk of SARS-CoV-2 reinfection associated with emergence of the Omicron variant in South Africa.”13

Pulliam provides an overview of her team’s work and “new findings” on a twitter thread from Friday. It begins:14

We have updated our preprint on SARS-CoV-2 reinfection trends in South Africa to include data through late November.

We find evidence of increased reinfection risk associated with emergence of the #Omicron variant, suggesting evasion of immunity from prior infection.

Astoundingly, this “update” comes hot on the heels of the original version of the paper, posted a few weeks earlier, which only included results to June 30. In Pulliam’s November 15 tweet, reviewing the version posted on the 11th (emphasis added):15

New preprint on SARS-CoV-2 reinfection trends in South Africa. We find no evidence of increased reinfection risk associated with circulation of Beta and Delta variants, suggesting limited or no immune escape.

A reader would be forgiven, likewise, for ceasing to read here. Things already stink to non-peer-reviewed high heaven. Just how is it that the same paper which waited 19 weeks to declare “no evidence” of higher reinfection rates for Delta - information that would have been rather enlightening if delivered back in the summer - has been updated to issue an opinion on the reinfection rates “for Omicron” after five days?16

And, why does the paper uncritically include the November 23 data-dump created by National Institute’s sudden decision to include antigen tests in their daily case counts,17 resulting in the addition of 18.5 thousand new cases on a single day - four days prior to the data cutoff the paper uses in the update?

Deciphering the effect the November 23 NICD data dump had on the figures rush-presented by Pulliam, et al. is not easy. The cases are definitely included in the new results in some fashion:

All positive tests conducted in South Africa appear in the combined data set, regardless of the reason for testing or type of test (PCR or antigen detection), and include the large number of positive tests that were retrospectively added to the data set on 23 November 2021.

NICD clearly dates these “cases” as “November 23” for the purposes of their outbreak reporting system (which is used to supply the figures in JHU/Google dashboards). In the media statement posted the same day, they describe this data dump as consisting of 20,813 positive rapid antigen tests “identified” as of November 8 (only something like 18,000 cases seem to have made it to the dump on the 23rd).18 Do the Pulliam, et al. values for before June 30 reflect these added cases? Possibly. Overlaying the November 11 and December 2 versions for NICD-recorded “infections” up to June 30:

There seems to have been at least a slight adjustment upward, toward the end of June - though, this may have reflected cases processed in early July, depending on how and when the NICD data for the first version of the study was accessed.

And just how do Pulliam, et al. assign the “date” of an “infection” to begin with? The following enigmatic description appears in the study text (emphasis added):

The specimen receipt date was chosen as the reference point for analysis because it is complete within the data set; however, problems have been identified with accuracy of specimen receipt dates for tests associated with substantially delayed reporting from some laboratories. For these tests, which had equivalent entries for specimen receipt date and specimen report date that were more than 7 days after the sample collection date, the specimen receipt date was adjusted to be 1 day after the sample collection date, reflecting the median delay across all tests. […]

This implies the existence of a “sample collection date” value for the cases dumped on November 23 - but also directly states that these values are not necessarily “complete within the data set.”

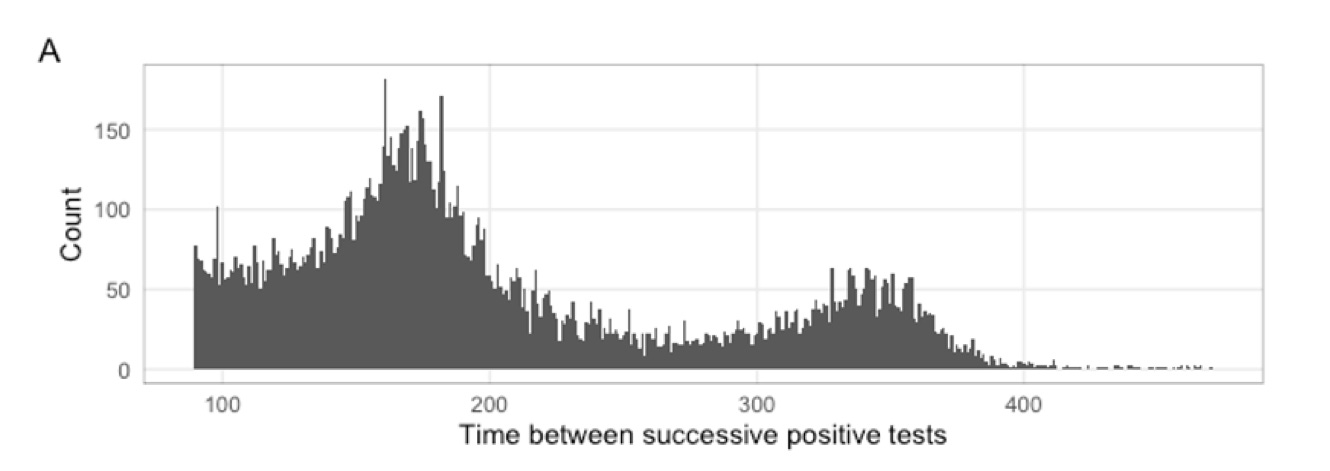

And complete or not, how much faith is meant to be placed in the accuracy of the recording of those dates? The rest of their “adjustment,” as described, is not any guard or check against incorrect or missing sample dates, but only for receipt dates (the value they use to plot “infections”) that are more than 7 days after the sample date - but what if the sample date is wrong? The authors do not refer overtly to any “infections” excluded for missing sample dates, nor to corrected sample dates. Since “reinfections” are defined as NICD-recorded “infections” for the same individual that are more than 90 days apart, the potential inclusion of any redundant, delayed test results with incorrect or missing sample dates is troubling.

It only would have taken a few hundred delayed antigen tests - corresponding to already-recorded “infections” 90 days or more prior to November 23 - in the NICD data dump to account for the entirety of the “reinfections” plotted by the authors at the end of the month; such delayed results could thus certainly have driven most, much, or at least some of the upswing as well.

The authors’ plot of “2+” reinfections offers little assurance on this front. Late November, circa the data dump, brings a surge of “third infections” that could potentially reflect delayed rapid antigen tests from previously recorded “Delta reinfections”:19

This possibility, alone, could account for the sudden rise in “relative” reinfection rates (reinfections vs “primary” infections) which constitutes the most astonishing “finding” of the December 2 update:20

But even setting that possibility aside, it should be noted that the “hazard ratio” demonstrates a clear pattern of lower quality data during periods of lower transmission (the space between colored bands). This is as should be expected, as during periods of lower transmission between waves, more “cases” will consist of false-positives in general. Since “reinfections” are rarer than “infections”, they will have a higher false-positivity rate in these periods. November, despite the rapid antigen test data dump, still comprises a low-case-rate period, with lower-quality data than the Delta wave with which the incipient “Omicron wave” is being compared.

Additionally, even if none of the reinfections plotted at the end of November consist of delayed (redundant) Delta wave infections, the evident lack of backlogged cases for before June 30 imply that the “new” (post June 30) and “old” NICD data can no longer be compared side-by-side: The inclusion, or heavier use, of rapid antigen tests has changed the scale by which “case” rates are measured.

There is no justification for Pulliam, et al. to have released an impromptu update to their conservative, delayed appraisal of the Delta wave based on a trickle of cases in November. There is something odd about the authors having done so immediately after the distorting change to the NICD data set. And there is something frankly galling about their confident attribution of the low quality, possibly out-of-date NICD “November” case data to Omicron, when there was so little awareness about the thing at the time that the authors were still actively publishing results about Delta!

Kids in Hospitals in South Africa!

Coming full circle, the media has spent the past few days gleefully seeding rumors of a sudden avalanche of hospitalizations of children under 5 in South Africa, based on statements by none other Public Health Specialist Waasila Jassat. A representative sample of the weekend’s deceptive reporting appears via The Daily Beast:22

“Unprecedented,” however, is merely a reference to NICD wonk Michelle Groome’s atemporaneous marveling at the effect the November 23 data dump had on her own agency’s calculation of the 7 day case rate average, not on hospitalizations for kids (emphasis added):

Groome sounded the alarm over the “rapidly increasing” seven-day average of cases which has gone from 332 on Dec. 1 [in fact, rates were last at ~300 on November 22] to 4,814 today [also incorrect].

She said: “If you have a look at the slope of this increase, you can see that we really are seeing an unprecedented increase in the number of new cases in a very short period of time, really just climbing right up [you don’t say].”

But in the conference call The Daily Beast uses to concoct their montage of devastation, only Jassat seems to mention increased hospitalizations of children. In a follow-up interview given on the 3rd with Shahan Ramkissoo, however, she prudently observes that this increase may partially be a result of the lower standards for admission that are usually prevalent at the beginning of a wave:23

Another reason is it’s likely that in the early part of the wave and the late part of the wave, when there are hospital beds, it’s likely that when cases are diagnosed in children, GPs might, as a precaution, admit them, even if they’re quite mild.

Jassat’s observations should nonetheless count as a “warning” for readers in the US - as the same lowering of admission standards for children likely has taken place here throughout 2021,24 fostering a never-ending stream of reports of “increased hospitalizations,” headlines of an “Omicron surge” in child admissions are sure to arrive any second…

“Fourth wave still predicted for November: Minister.” (2021, August 27.) sabcnews.com

Wadee, Inayet. (interview) “SA hospitals have seen influx of patients amid emergence of COVID-19 Omicron variant.” (2021, December 1.) youtube.com

“When the fourth Covid-19 wave is expected to hit South Africa: expert.” (2021, August 17.) BUSINESSTECH.

See “Saving Private mRNAyn.” “Was implicated” does not refer to mainstream opinion, but rather to the fringes of opinion on the virus discussed in that post. “Top virologist” is a reference to Bedford’s recent anointment by MedPage Today.

As I have now learned that AstraZeneca’s 30,000 trial subjects were “present,” by country, during the emergence of Alpha (UK), Beta (South Africa), Delta (India), and Gamma (Brazil), (as well as the vaccine being trialed in Japan and the US, where no variants of concern arose) the theory of vaccine-trial-driven spike mutation deserves a revisit.

Beta, despite eventual obsolescence, outscored Delta on numerous “antibody evasion” simulations (See NIII Pt. 2), and seemed particularly resilient against the AstraZeneca crowd in South Africa (See Booth, William. Johnson, Carolyn. “South Africa suspends Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine rollout after researchers report 'minimal' protection against coronavirus variant.” (2021, February 7.) The Washington Post.)

A War on Virus, regardless of the particulars, will be waged by the state exactly the same way as the War on Terror: Via incredibly convoluted attempts to play with people’s minds, in order to create, or at least make tangible and targetable, “the enemy” that the state naturally envisions “the public” to represent. And that the fingerprints conceivably fabricated to create this enemy would extend “into the past” isn’t really such a stretch, as the War on Virus wasn’t really declared in 2020. It dates at least to SARS-1, if not earlier (since SARS-1, itself, is not exactly a pristine specimen).

An analog which springs to mind (both here, and frequently elsewhere) is the decade of machinations conducted by the Quai d’Orsay in advent of Germany’s mobilization against Russia. Perhaps those years of deep-state manipulation of the press in the service of the sidelining of conciliatory politicians like Caillaux and the promotion of militant Germanophobia among the Parisian elite, and overt manipulation of Russian policy aims, were not necessary to frame France’s role in World War I - perhaps it would have been well enough to let Germany mobilize against the figment of a planned war from France - and yet these efforts ensured that when the frame arrived, it both seemed intuitive and natural to the public sentiment at home and was logistically realizable in Russia.

This same acknowledgement must be made for the oldest of conspiracies. The acknowledgement therefor appears in War and Peace, as Bezukhov’s admission into the Freemasons - otherwise counter to the entire thesis of the novel which holds that history is driven by random, autonomous surges of consensus.

See “Being Cron Malkovich.”

(index link anchor)

Correction, December 6: Significant edits were made to this section, in light of the contradiction between the verbiage in the NICD November 23 media statement and the interpretation I derived from the study results (which assumed that the added rapid antigen tests were from after November 8). In the end, I feel my original interpretation was still plausible, but the analysis supporting that interpretation required a rewrite from scratch, to explain why I do not think the added rapid antigen test “infections” can be safely dated to “before November 8.”

Original text:

Without retroactively adjusting NICD case rates from before November 8 (the cutoff for rapid antigen tests added to the counts on November 23), the NICD data can no longer be used to compare November rates with the past. For Pulliam, et al. to pretend otherwise is astonishing. Edit: This may reflect a mis-reading of the NICD announcement on my part. Antigen tests may have been retroactively added to NICD infection data from before November 8. However, this does not rule out the possibility of delayed reporting as discussed below; in fact it increases the potential risk.

What Pulliam, et al. do offer is an adjustment for possible “late reporting” of test results, based on inconsistencies in turnaround for different regional testing sites (emphasis added):

The specimen receipt date was chosen as the reference point for analysis because it is complete within the data set; however,problems have been identified with accuracy of specimen receipt dates for tests associated with substantially delayed reporting from some laboratories. For these tests, which had equivalent entries for specimen receipt date and specimen report date that were more than 7 days after the sample collection date, the specimen receipt date was adjusted to be 1 day after the sample collection date, reflecting the median delay across all tests.

Supposing that any faith can be placed in the recording of “sample collection dates” (despite the fact that they are, per the text above, not “complete within the data set”) or the authors’ intentions in general, this would imply that delays between sample and “infection” date range from 1 to 7 days. A rapid antigen test collected on November 10, for example, should show as an “infection” on November 11, even if the specimen receipt date was included in “the data set” as November 22. And it should only show as a “reinfection,” per the authors, if the same individual’s previous “infection” date was more than 90 days prior to November 11.

Somehow all of these exclusions, corrections, and cross-references were successfully made in five days (between the data cutoff and the update). But the plotting of cases doesn’t suggest any successful correction for the November 23 data dump:

If huge backlog of “cases” added to the NICD counts on November 23 included antigen tests dating from November 8, and the authors’ adjustment claims to plot “reinfection” dates as sample collection dates +1-7, it is odd that almost no uptick in “reinfections” appears in mid-November. And if the authors’ data can’t show their “work” in adjusting to the sample collection date in mid-November, why should the reader trust that these samples are even from November to begin with?

Is it really outside the realm of possibility, given the inconsistencies in specimen reporting in South Africa, that some of the antigen tests added to the counts on November 23 were dated from before November 8? And if so, wouldn’t that mean that the authors are not reporting reinfections in late November, but delayed antigen tests from previously counted infections?

This possibility, alone, could account for the sudden rise in “relative” reinfection rates (reinfections vs “primary” infections) which constitutes the most astonishing “finding” of the December 2 update.

Pulliam, J. et al. “Increased risk of SARS-CoV-2 reinfection associated with emergence of the Omicron variant in South Africa.” medrxiv.org.

The potential “impression” that Omicron has caused 35,670 reinfections refers to a trend in third-party descriptions of the updated (and re-titled) paper. As an example, headline: “Omicron causes increased reinfections”; text: “The study looked at 35,670 reinfections in South Africa. During the study period, Omicron was associated with a strongly elevated risk of reinfections.” But the study period, and the 35,670 reinfections within it, is from March 2020 to date. Omicron is only “associated” (sans sequencing) with the few hundred (potentially mis-dated or redundant) “reinfections” in November.

@SACEMAdirector (2021, December 2.) twitter.com

@SACEMAdirector (2021, November 15.) twitter.com

The November 11 version of the paper is conspicuously inconspicuously titled, “SARS-CoV-2 reinfection trends in South Africa: analysis of routine surveillance data.”

Somewhat hilariously, the paper is by the “Rapid Response” team at SACEMA, an acronym which includes epidemiological and excellence in the same “E.”

Per the site, which recycles the Pandemic™’s signature “flatten the curve” graphic, the mission of the team is to help “agencies plan rapidly for an evolving situation with little certainty even about the present state of affairs, much less the future.”

Unless, of course, the situation is “evolving” in a light that makes immunity appear resilient, as it did in the NICD data for June. In which case, “the present state of affairs” can safely be reported four months after the fact.

Right.

No conspiracy here…

-

As of 8 November 2021, we have identified approximately 75 000 antigen tests that need to be captured into the database, of these tests about 20 813 were diagnosed as positive for SARS-CoV-2. […]

There have been extensive engagements with the National Incident Management Team, the Provinces, the NHLS and the NICD, and we have included these data on the 22 November, so that it would reflect on today`s report.

-

and Pulliam, J. et al.:

-

Data analysed in this study come from two sources maintained by the National Institute for Communicable Diseases (NICD): the outbreak response component of the Notifiable Medical Conditions Surveillance System (NMC-SS) deduplicated case list and the line list of repeated SARS-CoV-2 tests. All positive tests conducted in South Africa appear in the combined data set, regardless of the reason for testing or type of test (PCR or antigen detection), and include the large number of positive tests that were retrospectively added to the data set on 23 November 2021

-

See footnote 17.

Chronic infections lasting longer than 90 days could also be a driver of mis-classified “third” and “fourth” infections in general, due to the high prevalence of HIV in South Africa. Thus, some of the November “Omicron surge” could be a data artifact of chronic infections which are “re-qualifying” 90 days after the previous surge. However, this same hazard was almost certainly present during the Delta wave and did not drive a similarly “abrupt” increase in recorded reinfections.

(index link anchor)

See the not-at-all meaningfully named Sykes, Tom. “Omicron Triggers ‘Unprecedented’ COVID Surge Hitting Children Under Age 5 in South Africa.” (2021, December 3.) The Daily Beast.

Ramkissoo, Shahan. (interview.) “COVID-19 in SA | Suffer the little children.” youtube.com

Reference pending (lost link).

Fun fact, Delta Omicron is an anagram of Media Control.

Ah yes, the OLD "you can get reinfected with this weird modern magic virus" trope. We debunked that one within 2 weeks in 2020 when the Samsung contact tracing app was shown to be buggy and was duplicate-counting priors on delay. Nobody in Korea was ever re-infected, but by then the media fell in love with it and ran with that meme. Now they are trying the Old Playbook with Omicron for one last hurrah. (Please let it be the last.) If true, can we predict what will be the next agitprop talking point? I will predict: "You really shouldn't take ibuprofen for Omicron."