Being Cron Malkovich

Viruses, variants, and the metaphysics of identity. Plus: dolphin measles!

Who we are - our identity - is paradoxically defined by who we are not: Our differences from others, or the reactions elicited in others by our behavior.

To be silent in the middle of a wedding party is to be “aloof;” to be loquacious alone in a prison cell is “crazy.” The acts are not what determine the identity, so much as the people who surround the acts. And at least some aspects of human identity are outright relativist fictions. Measured by ability to knock over full grown trees bare-handed, no human is “strong.” The fictional identity of “strong” only appears in comparison to other, even weaker humans. So members of a village can say: “Ah, look at Hans lift that log. He is strong.” But if all the other villagers, from cripples down to tots, suddenly gained the knack of knocking over trees bare-handed, Hans would no longer be seen as “strong” for his contributions to log transport.

So it is, too, with viruses. The measurement of the “strength” - or “virulence” - of a virus is simultaneously a measurement of the “strength” of ourselves. Humans are paradoxically the measurer and the measured; the virus thus becomes a mirror.

When the mirror changes name, we project changes onto the “new” version of mirror that reflect our pre-existing belief in what the “real identity” of the mirror is, and then go looking for signs of the validity of those projections in “reality” as measured by, again, our own bodies. Or perhaps by synthetic representations of the proteins previously made by our bodies in reply to the virus, as if when our “bodies” are virtualized and statistically abstracted - made “objective” - they can continue to say anything about our subjective reality. The point is not that changes to the “identity” of the mirror do not happen - only that to look for those changes is to forget that it is a mirror.

In the case of SARS-CoV-2, to instinctually align changes in identity to our own assigned updates to the name of the mirror - to once again take a subjective, fluid reality and “make” it objective and concrete, by scoring gene changes according to some statistically-imagined gauge that can certify “This is evolution”1 - is itself another form of projection. When Delta was declared to arrive in the summer, it was imagined as “weaker” at the time and “stronger” in retrospect, depending on how many elderly in heavily-Covid-vaccinated countries exited the ~4 month “infection efficacy” window.

And yet, even when “Covid-vaccine-mediated” changes to reality were acknowledged - thereby stepping out of the arbitrary construct that changes to name denote changes to identity - it was to portray the Covid vaccines as altering, of course, the identity of the virus in some negative fashion (namely, Marek’s Effect).2 Vaccine-mediated “weakening” of the human measurer was willfully interpreted as vaccine-mediated “strengthening” of the measured entity. This is absurd, of course. If all of Earth’s octogenarians teleported to Idaho at once, would that make the virus “stronger” in Idaho and “weaker” everywhere else? Marveling at the changes to the “strength” of Delta brought about by the mass re-entry of the elderly into the viral playing field mid-summer is akin to a baby wondering how grandma can disappear and reappear by waving her hand in front of her face.

Again, this is not to propose that the virus isn’t evolving in meaningful ways; that it is not ever getting “stronger” or “weaker.” But stronger or weaker, the virus will always be a mirror. To pretend we are capable of objectively measuring the mirror is to commit to fantasy.

A fantasy which entraps those who believe they understand viruses scientifically just as readily as those who imagine the virus is essentially a vengeful god.3 A fantasy which, in the scientific case, has one defining mantra:

“Viruses want to get milder.”

This axiom can be attacked not just for its wishful epistemic thinking, but on observational and theoretical grounds.

The theory, for the uninitiated, is that natural selection disfavors virulence. Because it is at least understood that the “mirror” of viruses will, from time to time, find themselves reflecting a new “observer” - by leaping from one species to another - it is understood that a given virus will find itself at least temporarily observed as “too strong” for its host. It must, the theory asserts, adjust to the new observer or it will be out of place, leading to limited burn-out,4 or to the oblivion of the “observer.” Since “observers” still exist, it is not unfair to imagine that their most successful “mirrors” have attenuated to them.

I am not opposed to this part of the theory; it fits well enough with my own crackpot “Immune Equilibrium” model.5 Quite literally, in fact: The general thriving of multicellular life implies a (retroactively observed) default of successful co-evolution between extant multicellular hosts and their most “popular” viral and bacterial “invaders;”6 what else to call this co-evolution but “equilibrium”?

The problem is the final claim, which constitutes the core of the axiom in question: And thus, viruses can never spontaneously get more virulent.

Axiom to Grind

As above, the first problem with the claim is that it ignores the variability of the observer by whose health, behavior, and ever-variable immune response “virulence” is defined. It ignores further the space between the observer and the mirror: The microbiome, the environment, and medical intervention (vaccines). Or, at best, it marginalizes the significance of that space by waving a vague wand labeled “seasonality” at it, or magically defining the impact of vaccines as a positive / negative binary defined by whether the vaccine in question is “sterilizing.”7 But this complexity cannot be waved away. In the past, present, and future, it is and will continue to be plainly observable in the general vagary of all infectious illnesses. Contagions behave mysteriously, and defy prediction, because they are fundamentally mysterious.

What the axiom claims, in other words, cannot actually be reflected in observed reality. Because the virulence of viruses is “measured” by a continually changing gauge, viruses will in fact be observed to “get stronger.” This, again, is exactly what happened with Delta in the summer. Whether it was really because of the waning of Covid vaccine “infection efficacy” or Covid-vaccine-driven viral enhancement is besides the point. The axiom was wrong. If observed reality is too subjective to reflect the axiom, the axiom cannot describe observed reality.

“Viruses want to get milder” cannot actually predict what will be experienced by infected hosts in the real world. It is a useless statement; a manifestation of intellectualized hubris in place of an assessment of probability.

For if the “axiom” were truly an axiom, why would there be any counter-examples?

Case Study 1: Influenza, UK, 1968-70

In July of 1968, a “novel” variant of the A2 influenza strain, which had dominated most flu seasons since 1957, was associated with a sharp rise in illness in Hong Kong.9

By August, the strain was identified in London, and rises in cases in other parts of Asia generated expectations that the Hong Kong variant would significantly evade the immunity built up from the last decade of exposure to the original A2, and to last years’ busy season with two prominent variants at once (preceded, one year earlier, by almost no signs of flu at all).

By the end of next spring, some unknown number of Brits had been exposed. 31% of adult male volunteers in the London district of Lambeth had a four-fold increase in antibodies by the summer. 4.97 million claims for “sickness insurance benefits” had been registered from the preceding December to April - 1.04 million more than in the 66/67 “no flu” season - with the rise spread out over several months in the late winter. 31,000 “excess deaths” from all causes were recorded, compared to the baseline for the “no flu” year. That “cases” for flu continued to be reported into late spring, meanwhile, reflected widespread public awareness of the virus. But by April and into autumn, the virus “went away” as normal.

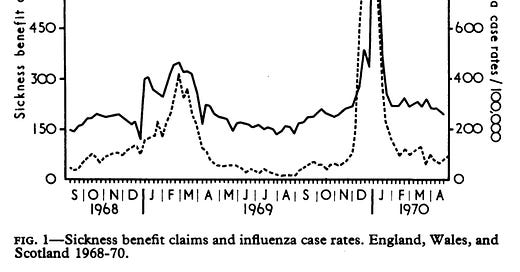

The next winter, despite the significant previous exposure in late winter of 68/69, with corresponding generation of immunity and “removal” of the most vulnerable - despite the variant, in other words, no longer being “novel” - winter call-out claims climbed to 5.47 million, and “excess deaths” from all causes landed at 47,000. Almost all of the excess corresponded to a giant spike in flu cases that, this time, was not spread out like in the previous season. All told, ~10,000 deaths would be attributed directly to influenza in the 69/70 season - 10 times more than the first season in which the Hong Kong variant landed ashore. And yet it was the “same” virus:

A “novel” version of an existing virus that spreads and kills more in the second year than the first. Seem familiar?

So just what happened in Britain in 1969? The obvious happened: The virus got less mild.

Wisely, the authors acknowledge that this real-life defiance of epidemiological conventional wisdom has several plausible human and environmental explanations (emphasis added):

The factors responsible for the differences between the epidemics are not apparent. The virus in both years was the same. Vaccination was probably used on too modest a scale to have modified either epidemic to any important extent. The proportion of the population which had antibody was much greater after the first year's outbreak than it had been before, which might have been expected to reduce the likelihood of a second epidemic or to modify its intensity. Other environmental features that may account for the difference, such as weather, air polution, population movement, and extra crowding for seasonal reasons, have not been evaluated. It may be that a combination of circumstances was responsible. It is clear that firm predictions of epidemics cannot be made without further study of the interaction between the many variables that determine their occurrence.

Admissions of “virus gonna virus” in formal epidemiological research, after the humbling era of mysterious poliomyelitis outbreaks, are rare. The entire exercise of epidemiology, after all, presumes from the outset to be able to predict epidemics without study of the interaction between the many variables that determine their occurrence.

To the obvious factors bravely proposed by these authors, we can add two more: Super-seasonality, and the virus itself.

“Super-seasonality” is a label I have provisionally applied to the current pattern of cases in SARS-CoV-2. Basically it is a naked description of reality. “Year 2” had more cases than “Year 1,” largely regardless of Covid vaccine uptake: That’s super-seasonality.

One mechanistic explanation for super-seasonality, also applicable to the Hong Kong variant in Britain, is that “novel” versions of familiar viruses have to compete, in some form, with previously prominent versions. Another is that both “novel” viruses - the Hong Kong variant, and SARS-CoV-2 - were not in fact novel to begin with, and cross-immunity from an undetected ancestor variant was stronger in the first year, and waned just a bit in the second. If the first confirmed carrier of the Hong Kong variant was a London child with no contacts to anyone who had traveled to Hong Kong, after all, isn’t it possible that the variant, or a close ancestor, had been in Britain well before its detection half-way across the world?

Both of these explanations imply that the antigens by which viral strains are so often defined, and our immune responses to them, are constantly changing in imperceptible ways; the “mystery” of super-seasonality merely arises as an artifact of our pattern-seeking view of reality, which creates “difference” where there is none, and misses it when it is there.

Defining the virus as the antigen is only a particularly obvious example of this. When the authors describe the Hong Kong variant studied in 1969 as the “same virus,” what they mean is that antibodies that bind to one version bind equally to the other. This makes no account for changes to the rest of A2’s genome, including the incredibly intricate orchestra of gene transcription and immune suppression that occurs during replication within a cell; changes to these elements of the genome could not be detected in 1969.

In 2021, such changes can be detected, and are actively tracked by resources such as nextstrain: But as quantifying the corresponding change to “the virus” represented by a modification to “ORF 8,” for example, is impossible, endeavors such as nextstrain elide the fact that a small change in the latter can represent an entirely new temperament in the former. What does “1 change” to such mysterious genetic algorithms actually equal? With no possible knowledge of the scale represented by “1,” we might as well not quantify such changes at all.

In the perception of the authors, the Hong Kong variant of the second winter was “the same” virus. It is possible that in quite significant ways, to do with competent replication within the cells of Brits, it was different. It is possible that it used its first year to get better at infecting, and killing, its host. It is possible that it got less mild, because there was some fitness advantage to doing so.

It is possible that first Delta, and now Omicron, have done the same. I am varying degrees of skeptical on both counts, and have voiced my intuition elsewhere that coronavirus is already at a baseline of “full aggression,” implying there is no increase in virulence possible.10 But such an increase is at least one potential explanation for the super-seasonality observed in 2021.

Case Study 2: Polio, USA, 1944

If the axiom holds that all viruses “want to get milder,” polio virus in the 20th Century clearly did not get the memo.

But here, a bit of perspective is in order. Even when observed “paralytic” cases of polio surged locally and nationally in various years throughout the 20th Century, it was a rare condition. Since exposure to polio is universal, an increase in rare severe outcomes does not correspond to a meaningful decrease in mild outcomes. You can fill a hospital with the .1% of children who end up on an iron lung for a photo op; it doesn’t erase the 99.9% of children who are fine.

This is still more or less true even accounting for the apparent differences in temperament among polio sub-strains. Despite lacking DNA sequencing, polio researchers were able to observe differences in apparent virulence even among the antigenically “identical” versions of the virus they collected from myriad outbreaks in order to organize the virus into three major strains. For even the “worst” of these sub-strains, death of the host was a rare outcome. The axiom is not really challenged by the possible emergence of such sub-strains as a cause of the surge of 1944.

But I have included the polio surge here (at the risk of spoiling the larger essay on the subject which is in the works) as an exemplary candidate for the possible role of the microbiome in unpredictable increases to “virulence.”

Polio virus seems to rely for efficient access to target cells on molecules released by bacteria in the gut.12 This, in fact, makes intuitive sense: If the cells lining the gut are never encountered in absence of bacteria, why wouldn’t viruses be optimized for working within the chemical milieu created by said bacteria?

Yet it’s counter-intuitive at the same time. We now recognize the microbiome, on balance, to play an important role in healthy immune function; but even “positive” changes to the microbiome based on diet or the weather could account for why polio virus was typically observed to be “in season” during the summer (so, too, could the common paranoia that house-flies were transmitting the virus).

Could a change to weather or diet, with a corresponding over-abundance of the bacterially expressed chemicals favorable to polio virus, have contributed to the 1944 surge? Possibly. Could suppression of the microbiome, perhaps due to experimental use of DDT in 1944, have done the same? Possibly.

The same dynamic is possibly relevant for coronavirus, as well. It could, for example, account for the differing susceptibilities of regions with different diets to infection with the virus.

The modern era has brought with it international travel, internationalized and synthesized cuisine, extended time spent indoors, and heavy use of antibiotics; all of these have contributed to the generalized, constant destabilization and homogenization13 of human microbiomes. If viral replication is sensitive to changes in the microbiome in both positive and negative ways, the logic of the axiom is thrown into serious question.

The virus does not pre-determine the microbiome of the host, and cannot evolve to widespread changes in advance of suddenly becoming “more virulent” as a result.

Case Study 3: Dolphin Morbillivirus, Coastal Atlantic, 2013-15

1,600 bottlenose dolphins were stranded along the eastern coast of the US between 2013 and 2015, an eight times increase in the normal rate. These dolphins seemed predominately to derive from coastal stocks with a total estimated population of ~26,000, implying a 6% fatality rate - with possible undercounting, since not all deaths may have resulted in stranding. This surge in stranding was apparently driven by an outbreak of infections with the dolphin version of measles; in other words, a common virus.15

Here, as with polio, we could cite plausible environmental factors which contribute to the sudden increase of “virulence” - pollution, stress from human shipping and fishing, strange weather, etc. - except it’s not clear that there was an increase in virulence to begin with. Other outbreaks have driven large scale epidemics among dolphins and related mammals in the recent past. Is high mortality from infection the norm, or a modern aberration? With no ability to study the dynamics of “normal” infection with Dolphin Morbillivirus in advance of the era of humanity’s war on cetaceans, the existence of a former “equilibrium” between this virus and its host is merely a guess.

Dolphin Morbillivirus might demonstrate that even an ancient, well-acclimated virus is perfectly comfortable defaulting to high virulence. Or it might demonstrate, again, that subtle changes to the dynamics of population sorting and not-so-subtle-changes to the environment, can dramatically dysregulate the balance between viruses and their hosts - and that these imbalances, once introduced, can take decades to be resolved, if not longer.16

Either one of these potential realities totally refutes the axiom.

If Dolphin Morbillivirus self-evidently “wants” to stop killing its host, why hasn’t it done so?

Koyaanisqatsi

I mentioned that the theory underpinning the axiom can be attacked on theoretical grounds; but also that I agree with the theory. This contradiction stems from the utilization of observer bias in the theory.

What is “observed” is the species that have thrived on Earth to date. These, by their very existence, imply a homeostasis or “equilibrium” with their bacterial and viral passengers. But their observed thriving to date doesn’t say anything about what will prevail as those species cease to thrive - or when sudden changes to ancient behavioral patterns are introduced. Calamitous imbalances, such as may already be underway between dolphins and their version of measles, will likely become the norm as the planet continues its path toward mass extinction.

To a coronavirus or influenza virus, for example, modern humans must seem like a totally new host species. The host they knew before gave birth almost immediately after birth and did so repeatedly; often worked or warred itself to death before middle age; already suffered plenty from diseases transmitted by parasites galore; and spent large swaths of time outside. The host they know now is older; scarcely replicates; endures little mortality burden from parasites; and “visits” outside only when free time can be found to do so.

Who’s to say that sustained “low virulence” in a respiratory virus is even possible under such conditions?17

This time merely in order to “prove” we “understand” reality.

See: el gato malo. “are leaky vaccines driving delta variant evolution and making it more deadly?” (2021, October 10.) bad cattitude (emphasis added):

-

what we see is not what one would expect from a virus. none of the other variants (pre vaccine) worked like this. none saw CFR rise like this. and no jump from major variant to variant saw a statistically significant rise in deadliness.

this IS however what one would expect if a virus were undergoing vaccine mediated evolution (as mareks disease did in chickens) and selecting for hotter strains because vaccinated people can carry and spread them and not die.

experienced CFR on delta is nearly 7X what it was in the beginning of june and has been galloping since the middle of july.

-

Vaccinated people, of course, can also (once they leave the “infection efficacy window” after June) “carry” the virus and die - even by coincidence. Especially if nearly all of the elderly in the UK are vaccinated.

For my argument on why Marek’s Effect cannot apply to a coronavirus, see “Crackpot Corner: Marekspocalypse Edition.”

See “In Orphania: Pt. 2.”

“Limited burn-out” could be seen as evolutionary false-starts. These might be the common outcome, depending on the niche the virus occupies (rare or frequent transmission).

Rabies, when it crosses from more acclimated species into dogs or humans, burns through the central nervous system and back out through the salivary glands, rarely triggering dormancy in time to prevent death. Because this is only a so-so method of transmission, rabies does not have enough chance to serially improve its genetic formula to these potential new hosts. It doesn’t really seem to matter if rabies “wants” to get milder. There are biophysical constraints to the niche of “bite transmission” that make the evolutionary feat of adjusting to a new species difficult.

See “Burned All My Notebooks”!

(I feel that the long-delayed edit and follow-up to that essay is finally nearing emergence into reality. Interested readers can meanwhile check out yesterday’s comment thread, prompted by Markael Luterra (who writes at The Dendroica Project), regarding whether coronavirus can become a chronic infection according to my version of the theory.)

Allowing, again as with rabies, that rarer-but-compatible viruses and bacteria are not as well co-evolved with their hosts.

When, again, there are plenty of counter-examples of “non-sterilizing” vaccines being used without apparent negative consequence, or with negative consequences that were nonetheless not consistent with Marek’s Effect. Most particularly with the non-sterilizing smallpox vaccines, which were aggressively used for over a century despite rolling outbreaks, seemingly driving worse outbreaks in some locales while the virus nonetheless became milder globally (as subjectively observed) - see “Funeral for a Fact.”

All figures in this section from Miller, D. L. et al. (1971.) “Epidemiology of the Hong Kong/68 Variant of Influenza A2 in Britain.” British Medical Journal. 1971 Feb 27; 1(5747): 475–479.

See, again, “Crackpot Corner: Marekspocalypse Edition.”

(index link anchor)

See Kuss, S. et al. (2011.) “Intestinal microbiota promote enteric virus replication and systemic pathogenesis.” Science. 2011 Oct 14; 334(6053): 249–252.

-

We depleted the intestinal microbiota of mice with antibiotics prior to inoculation with poliovirus, an enteric virus. Antibiotic-treated mice were less susceptible to poliovirus disease and supported minimal viral replication in the intestine. Exposure to bacteria or their N-acetylglucosamine-containing surface polysaccharides, including lipopolysaccharide and peptidoglycan, enhanced poliovirus infectivity. We found that poliovirus binds lipopolysaccharide, and exposure of poliovirus to bacteria enhanced host-cell association and infection. The pathogenesis of reovirus, an unrelated enteric virus, also was more severe in the presence of intestinal microbes. These results suggest that antibiotic-mediated microbiota depletion diminishes enteric virus infection and that enteric viruses exploit intestinal microbes for replication and transmission.

-

As in, a loss of wide-spectrum bacterial diversity nourished by constant exposure to dirt.

(index link anchor)

All figures in this section from Morris, S. et al. (2015.) “Partially observed epidemics in wildlife hosts: modelling an outbreak of dolphin morbillivirus in the northwestern Atlantic, June 2013–2014.” J R Soc Interface. 2015 Nov 6; 12(112): 20150676

Although it hazards the “mere guess,” my intuition is that this is the more likely state of reality.

Which brings me to the actual point of all this nit-picking. I am in favor of not being afraid of the virus. But a “not being afraid” based on overly rosy predictions for mortality rates going forward, especially among the elderly or unhealthy, especially after two years of stress and lockdown, are not sustainable: A true faith is required, one rooted as I have written previously in “our biological fates” - the intellectualized faith of an axiom that merely memory-holes all current and past counter-examples will not be enough to re-embrace a life of inherent risk, and inevitable death.

The human idea of vaccination, and modern ''vaccination'' even more so, is based on the following assumptions, which are not described anywhere in such a way, but which must be presupposed in such a way if vaccination/''vaccination'', according to science, is to be a good idea:

- all people live under the same environmental conditions

- all people eat the same food and have a good nutritional status,

- each person's metabolism works the same as everyone else's,

- every human being has the same immune system,

- every human being reacts in the same way to completely different external influences,

- every human being receives the same vaccination at the same time and in the same place,

- every human being has the same "normal" genome, whatever "normal" means,

- every human has the same viral gene sequences in her/his genome from previous infections,

- every human being reacts the same way to the same vaccination,

- every human being feels the same way about the administration of the vaccine,

- you are me and I am you and everybody is everone else

- we are all the same person and we hide this inconvenient truth behind different facades.

That's science, what else.

Fantastic. In my eyes, your best text yet. ''Best'' in the sense of bio-logical coherence and our place in that coherence.

Viruses are indeed the messengers between the epigenetic influences of the environment and the genetics of all living beings, including us humans of course. Thus, symptoms are the vocabulary of the course of each individual disease history. Ignoring or eliminating the vocabulary does not mean that the story never happened, only that it can no longer be told. And the longer it goes untold, the more untruths and misunderstandings accumulate.