The big new Covid vaccine efficacy in kids and teens study

A brief examination of the limited relevance of Wu, et al.

Summary

A large study has just been published claiming to find substantial severe efficacy for the Pfizer Covid vaccines in teens and older children. This post will briefly argue that these findings are not impressive (thus, there is no reason to read on unless the reader is already interested in this study or reports on the same). As a bit of meta-commentary, the entire reason I so frequently nitpick study results that incorrectly suggest negative Covid vaccine efficacy, is because every now and then, there will still appear a new study with a slightly different “packaging” which, unless nitpicked, suggests fantastic, great, stupendous Covid vaccine efficacy in kids.

This is the study (Wu, et al.):

After rummaging through the results and supplemental appendix, I find:

This study is probably just passing off temporary infection efficacy as severe efficacy.

To reinforce this feat of “efficacy laundering,” the study seemingly only looks at early post-vaccine severe outcomes (before infection efficacy wanes) despite the fact that longer observations were obviously possible and relevant in the case of teens vaccinated in 2021. (However, the duration of observation of severe outcomes for the Omicron era isn’t 100% clear. As best as I can tell, severe efficacy is not monitored for the full term.)

Therefore, the study does not support the notion that Covid vaccines reduce severe outcomes in kids when they are infected.

Background (very briefly)

I have always been highly skeptical that the Covid vaccines could reduce already rare severe outcomes in children on biological grounds. Severe outcomes in adults result from immune suppression and delayed antibody generation. Even among older, “high-risk” adults, early production of antibodies in the course of infection is very protective against severe outcomes (comparable to Paxlovid treatment or vaccination): This is why most people do not need a Covid vaccine.

No one ever demonstrated that children and teens were failing to rapidly generate antibodies during their first-time infections with SARS-CoV-2. In the case that they are doing so (which I think likely) then there can be no benefit to pre-exposure when it comes to severe outcomes.

Many prior American studies on Covid vaccine efficacy in children have, however, been flawed in one of two respects. Either, entire health registries were evaluated, in which case children who might have left the state or region in question were incorrectly included in the “unvaccinated” denominator (see “The Immortal Unvaccinated Problem”). Or, they have involved test-negative designs, which are not a tool for producing knowledge about reality.

A preprint from last January — Lin, et al. — possibly suffered from the first limitation. Still, it suggested that severe efficacy rapidly dwindles toward zero in older children (5 - 11), which would reflect that there was never any “true” severe efficacy to begin with (only a temporary prevention of infections):

Notably, Lin, et al. has been languishing in preprint for a year, whereas this new study, which instead deliberately excludes long-term results in the severe efficacy analysis (as far as I can make out), has meanwhile been published. Curious. (Lin, et al. was limited to North Carolina but had a sample size six times larger than the new study; again, however, it may have suffered from the “immortal unvaccinated” problem.)

The CDC’s MMWR platform is meanwhile a frequent offender for test-negative studies. An example from last month claims to find severe efficacy in younger kids: Notably, the portion of Covid vaccinated kids among SARS-CoV-2 positive cases isn’t obviously different than their ratio in the overall population — suggesting zero actual severe efficacy. Hence the un-usability of test-negative designs.

On with this new paper.

Design notes

Wu, et al. (the new study) follow teens vaccinated in 2021 and older children (5 - 11) and teens vaccinated in 2022, producing one cohort for Delta efficacy and two other cohorts for Omicron efficacy. No results are given for the 2021-vaccinated teens after 2021; previously infected (according to the same health records being evaluated) are excluded from all three cohorts. Thus (as best I can make out) severe efficacy for all three cohorts is only evaluated for a few months. (Only for infection efficacy do the authors seem to make use of the longer observation period in the Omicron year cohorts.)

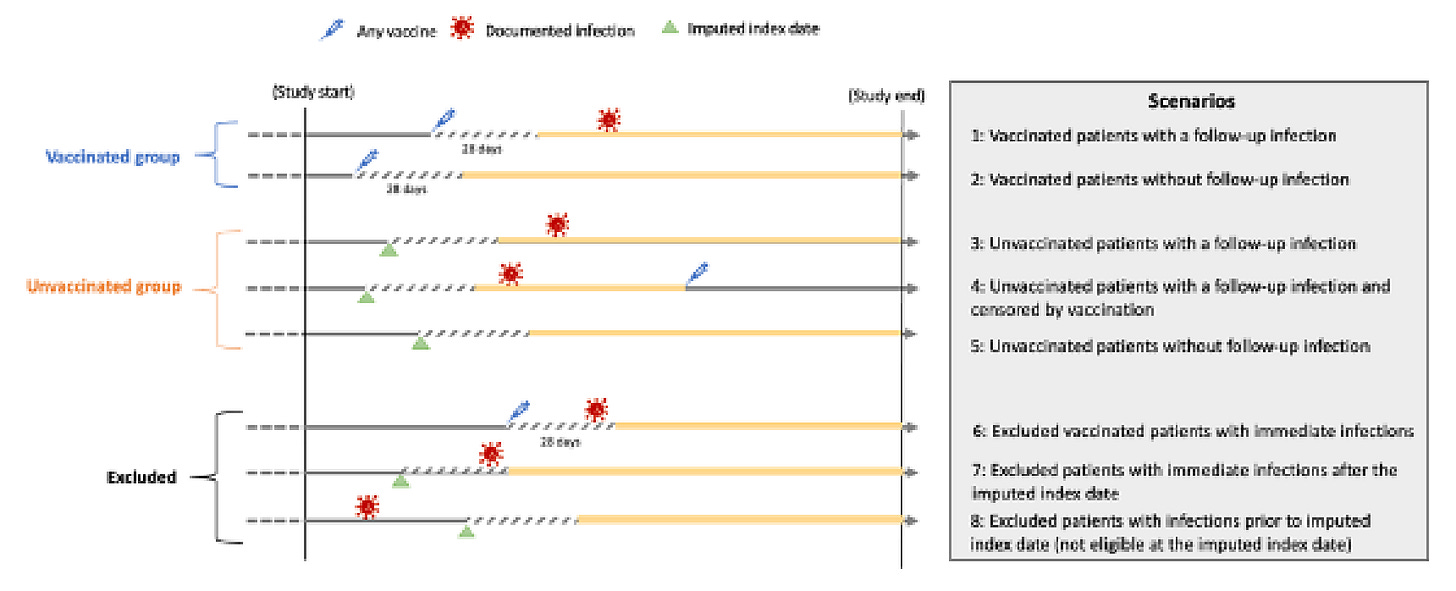

Unvaccinated pseudo-controls are roughly matched to the vaccinated in a way that reduces differences in exposure start-time and duration. Only those with a primary care visit within the prior 18 months were eligible for inclusion; this should reduce the distorting effect of “immortal unvaccinated” as mentioned in the background section. Any individual experiencing outcomes within 28 days after vaccination (for the vaccinated) or matching/recruitment (for the unvaccinated) is excluded from the main results (in other words, all the kids who were observed did not experience infections or related outcomes between day 0 and 27).

I see no major problems with the matching design that warrant further discussion.

Outcome definitions were problematic. “Severe” cases were defined as hospitalization for a litany of maladies within several days of a positive test (or other report of positive infection). ICU cases were defined likewise — being admitted to an ICU within etc. There does not seem to be any distinction between being hospitalized or ICU-admitted “with,” but not “for” Covid-19. (This may have been required to gather enough outcomes for statistical power, but in fact would render the results less robust.) However, since “severe efficacy” is not found to be very different from infection efficacy, this seems to be only partially relevant (because the results are already unimpressive anyway).

Defining “true” severe efficacy

There is no formal distinction between “severe efficacy” as usually reported and discussed — severe outcomes per-person — and in a sense that is meaningfully distinct from infection efficacy — severe outcomes per-infection. Despite the fact that the former definition is usually applied to “severe efficacy” in practice (such as in the Covid vaccine trials), it cannot be said to have any meaningful difference from infection efficacy: It simply means, less infections are happening (and so of course severe outcomes are reduced). The latter definition would instead ask and answer the question, “are severe outcomes reduced even if, over the long term, infections are not?”

This distinction isn’t particularly relevant on vaccines with long term infection efficacy. But this does not describe the Covid vaccines, which wane in infection efficacy after a 3 to 4 months (and even more rapidly with later and later courses of “boosters”) Additionally, the latter definition, which we may term “true” severe efficacy, is always relevant (regardless of infection efficacy duration) in the context of any claim to the effect of “this vaccine will reduce the likelihood of infection, and make infections less severe when they happen.”

Therefore, ignoring boosters, we may model the distinction between the two definitions — “pseudo-” and “true” severe efficacy — as follows:

To highlight from the comments, the essential deficiency of “pseudo-” severe efficacy is that there is no difference in the likelihood of severe outcomes in the long term. Besides a temporary delay (without the endless re-use of boosters), the same number of severe outcomes ends up occurring, and the vaccines are essentially pointless from the perspective of said outcomes.

Wu, et al. results:

Just ‘pseudo-’ severe efficacy in the short period after the first vaccine course (plus some “with, not from” efficacy, probably)

And so the results nearly speak for themselves:

Delta era (teens, vaccinated and observed in 2021):

Infection / severe (93.8, 99.4*) / ICU efficacy: 98.4% / 98.0% / 99%

Omicron era (children 5 - 11, vaccinated and observed in 2022):*

Infection / severe (65.9, 86.7*) / ICU efficacy: 74.3% / 78.7% / 84.9%

Omicron era (teens, vaccinated and observed in 2022):*

Infection / severe (78.9, 95.9*) / ICU efficacy: 85.5% / 90.7% / 91.5%

*Severe efficacy is reported separately in Supplemental Table 5. Since these outcomes were rare, I have included confidence intervals from the same table to the left.) The other values are from the main results, Table 3, which combines moderate and severe efficacy into one value.

While these results might seem to support “partial true severe efficacy” — with some 33 - 60% additional reduction of severe outcomes beyond mere prevention of infections — I do not feel that such a conclusion is warranted. These narrow margins are unimpressive in light of the loose standards employed for defining severe and ICU outcomes (discussed in the Design notes section).

Other questions

I did not ultimately spend enough time with this study to resolve a fundamental question: Do the Omicron era severe efficacy values even include observations for longer than 160 days after the first dose? (it is clear that this is not the case for the Delta cohort).

Ultimately, this is because the results regarding severe efficacy are not strong enough to begin with; there would be little point criticizing the paper further.

On myocarditis, etc.

Since outcomes within 28 days of the first dose are not counted, there is nothing interesting in the reported values for myocarditis (which find a lower rate among the vaccinated1). As best as I could tell, all-time myocarditis values are not in the supplemental appendix.

The authors do report that cardiac complications were more frequently observed in the vaccinated in the Delta era, though this is a small difference (1.22 vs. the unvaccinated).

A full reporting of all relevant outcomes would probably be similar to the Swedish teen vaccine study (higher myocarditis and other -itis’es in the Covid vaccinated).

If you derived value from this post, please drop a few coins in your fact-barista’s tip jar.

This is a correction to the originally published mis-statement that rates were lower in the unvaccinated.

That's part of what I like about your work Brian. You don't hold any science to be sacred, to not be challenged or called out for poor quality or method. Which is Exactly as it should be. $#!%%@ science should be called put WHERE EVER it is found, so we can all do, be better.😉

#wearescience #setthebarhigher #sacredcowsbegone

Please can you summarise your overall opinion on the vaccines?

I know several people who got infected ( mildly) within 2-4 weeks of a booster, therefore isn’t this study missing all those people if they don’t start counting until day 28?

Do the vaccines increase the likelihood of catching covid within the first month? I think yes.

Do the vaccines decrease likelihood of catching covid between ~ 1-4 months? I think they are neutral for infection but am happy to be corrected. Isn’t it difficult to tell because surely it depends on whether there was a wave occurring at time of ‘testing’ the theory?

Do the vaccines have any effect beyond 4-ish months? I think not.

At what point in these scenarios do you believe there may be ‘severe-efficacy’ ie. they are justified in saying ‘ but it would have been so much worse without a vaccine’! ?

I know you’ve written posts in the past about all this and I’ve read them all, but I read a lot and remember a little and I’m currently on holiday too! Thanks!