Update to the case against bacterial co-infection

Also, RE kids' innate immunity after vaccine and monkey brain virus RNA

I have made a slight addition to my prior post regarding the theory that “Covid-19” and deaths attributed to the same were secretly all caused by maltreatment of bacterial pneumonia (as recently litigated by Neil, et al.).

These additions regard the more niche aspect of the epidemiological properties of the virus and the claims (made in Neil, et al. but also elsewhere) that they were somehow “un-virus-like,” and so either must mean the virus is not a virus or the virus is being driven to wild behaviors by the vaccine, depending on the year and the author in question (what is perennial is the naivety of assuming that viruses must respect “immunology 101” talking-points or have their city-issued medallions revoked). The following points would probably have made it into the original post if I hadn’t been working mobile. The first three paragraphs are from the original, and the rest is new:

This misrepresentation of the state of knowledge is often reflected (either in this paper or elsewhere) in comments regarding the geographic and temporal irregularity of the virus’s spread in 2020; or the fact that the virus did not disappear or attenuate after the first year.

But neither of those things were actually unusual. They were observed and remarked upon in all three of the 20th Century flu pandemics.

The behaviour of influenza has seemed so erratic as regards its occurrence in both time and space that it has fascinated epidemiologists for many years

—Andrewes, 19531

A fact little-remembered today is that novel influenza outbreaks were often so geographically capricious that it was unsupportable for anyone observing propagation of the illness to claim that person-to-person spread is the exclusive means of the same. Reviewing the 1957 flu and three prior pandemics, Shope writes:2

However, certain discrepancies enter to spoil the perfection of the case-to-case transfer explanation for the spread of influenza during the second wave of the 1918 pandemic. These have to do with certain flukes in distribution, certain skips of large bodies of population. For example, Boston and Bombay had their epidemic peaks in the same week, while New York, only a few hours by train from Boston, did not have its peak until 3 weeks later(10). In like manner, Seattle, Los Angeles, and San Francisco had their epidemic peaks some 2 weeks earlier than Pittsburgh, which is just an overnight run from the infected eastern seaboard cities. In some respects, the epidemiologist had an easier time getting the pandemic disease transferred over long distances than in taking it to communities nearby. Thus, though it got to Chicago, presumably from Boston [but Shope really means to say that nothing of this nature can be presumed at all], fairly early and affected that city in September, it did not reach Joilet, just 38 miles away, until October. Similarly, it took 3 weeks to cross the little State of Connecticut from New London County to Fairfield County.

This is just to ground our expectations; any claims about how viral outbreaks “should” spread, i.e. what we should “expect” of them, warrant absolute skepticism.

And so, while the autumn wave of 1918 was one of many examples of rapid, global diffusion of influenza A, the spring- and summer-time outbreaks of H2N2 in 1957 offer precedent for a more limited and elusive outbreak. Before I quote from Shope again, let us review what Neil, et al. claim about spring, 2020:

The pattern of spread, and the geographical concentration of the Covid-19 mortality toll is not what one would expect from a respiratory virus. Deaths were highly localised in care homes and hospitals, within elderly age groups and those suffering multiple comorbidities and in specific cities and regions such as New York, Lombardy and Madrid.

For instance, by May 2020 the 'pandemic' in the USA had only occurred around a few points that could have been pinned on a map, and everywhere else failed to experience it.

Buzzer sound-effect, wrong, especially for an off-season outbreak of a novel virus. In summer, 1957, again per Shope:

In this country, the disease spread slowly, involving initially military establishments that had received personnel returning from the Orient. It appeared in various groups of civilians that congregated from different parts of the United States during the summer, most notably in summer camps and in a summer church conference at Grinnell, Iowa. Individuals returning from these meetings set up foci of infection in their home communities, and by late July and early August the disease was widely seeded throughout the United States. During the early part of the outbreak, Asian influenza showed little tendency to spread except on very close contact and tended to remain sporadic. With the beginning of autumn, the disease diffused more widely and rapidly than it had at first(1).

Thus 1957 is almost a perfect precedent for 2020; except that even in the winter, 2020 and summer, 2021 outbreaks remained contact-limited and sporadic. The transition to true “wide and rapid” diffusion was marked and explained by the extreme genetic modifications of Omicron, which retroactively explain the limited and sporadic nature of the virus’s spread before Omicron. This is another fact that is “hallucinatory” if one is trying to understand reality according to the Bacteria Theory model. What about the mutations to SARS-CoV-2 that gave us Omicron changed bacterial pneumonia?

The comments to my post were not as energetic or combative as I would have liked. What push-back I received amounted to murmurs of “oh pish-posh, Brian, actually so-and-so has repeatedly shown that…” — reflecting absolutely no engagement with the evidence in question. No one offered an explanation for how maltreatment of common respiratory illness can produce, for three years in a row, excess deaths that are two-fifths the annual number of hospitalizations for pneumonia in 2019 if at the same time only one fifth of people hospitalized for “Covid-19” actually died. Interest and belief in the Bacteria Theory of Covid-19 quite obviously outpace understanding of the issue, if no one can actually talk about the discrete problems and arguments. However, when belief outpaces understanding, it is just d ogma.

Now for some notes on unrelated studies that did not warrant their own posts:

Kids and post-vaccine innate immune depression

Berenson recently post a “VERY URGENT” review of the following study by Noé, et al.:

By “alters,” what is meant is that cytokine responses are rather consistently lower one and six months after transfection with the Covid vaccine than before, suggesting a lowering of innate anti-viral and anti-bacterial immunity in kids. What is most impressive is the apparent consistency of the response, with error bars suggesting that few kids replied by increasing their immune response to various viral or bacterial molecules (everything after the first four, which are related to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein):

Great, Vaccine Doom Confirmed, except for the thing that I find unhelpful about all these studies — there is no unvaccinated control group. It goes without saying that had there been such a control group, with kids who do not receive the vaccine but are sampled at similar time-points somehow producing similar results, we would need to look to a different explanation (e.g., local seasonal patterns in viruses and bacteria). I will never be satisfied by post-vaccine group biological response studies that leave out controls (and cannot help but think the intention is to get random assay noise past peer review).

Taking a more positive interpretation, could this explain last winter’s surge in childhood infections and subsequent hospitalizations? The authors of the paper acknowledge in the Discussion that no clinical outcomes related to immune suppression in children have been documented — though, I would note, there does seem to be a signal for such a detriment in the Swedish teen vaccine study by Nordström, et al. which I reviewed here (and it had a control group). However, even if this would explain perhaps a rise in traffic at healthcare settings, it would only represent a dozen or so extra hospitalizations for infections among 645,000 vaccinated teens.

I will note that another preprint appeared this winter which I have not yet reviewed, which seems to dampen the theory that childhood Covid vaccines are responsible for recent outbreaks, as opposed to the more obvious explanation of immunity debt.

In the American TriNetX database, which may only capture a portion of Covid-vaccinations but should be expected to be as accurate for kids positive for RSV as those negative for RSV (i.e., who had a healthcare encounter of some kind other than for RSV between May and November of 2022), both groups were reported-Covid-vaccinated at a rate of 3.5% (Table 1). Meanwhile, the RSV-positive kids were much more frequently reported as having been positive for the virus at some point (19.2% of RSV-positive vs. 9.7% of RSV-negative). So the Covid vaccine seems a trivial element in the case of the recent waves of RSV.

Overall, I do not think the new results by Noé, et al. are necessarily very urgent.

Monkeys and SARS-CoV-2 RNA in the brain

Another study making the rounds regards 6 apparently-recovered monkeys (green and macaques) having viral RNA in the brain regions near the olfactory bulbs even though they had apparently recovered from infection:

SARS-CoV-2 RNA Persists in the Central Nervous System of Non-Human Primates Despite Clinical Recovery - biorxiv.org

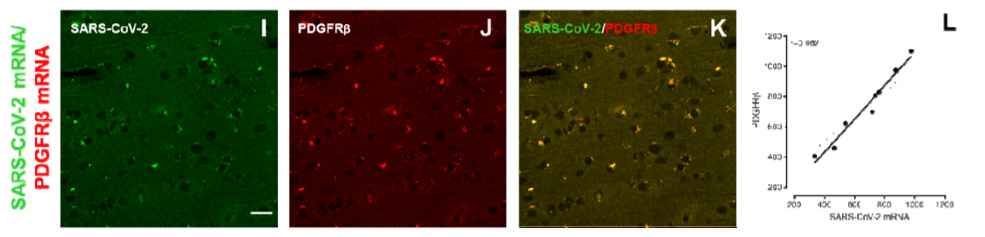

The basic finding is that RNA for spike protein is found (via in situ hybridization) in pericytes, which are cells that envelope capillaries in the brain and have ACE-2 receptors, at 21-28 days post-infection. The authors examined tissue from the olfactory epithelium (so the nose) and pyriform cortex/amygdala (the part of the brain downstream of the nose); so these results would not seem to exclude other parts of the brain. They found decreased ACE-2 (vs. uninfected controls), and high amounts of spike RNA in pericytes. They propose that this lingering persistence of viral RNA explains post-infection neurological symptoms in adults.

A, but le science, she is a wily creature. It should first be noted that these monkeys were all rather old — 13 to 16 years of age. In fact, the original paper reporting on their infection experiences specifically describes them as “aged;” the life-spans of the species in question are reported variously from 20 to 30 years. Their outcomes therefore might not apply to younger humans. The authors did not find any relationship between disease severity and amount of RNA, but such a relationship might have been apparent with younger and healthier monkeys included. As for humans, in the Hirschbühl, et al. series of autopsies mostly conducted at Augsburg, CNS and cerebrospinal fluid samples for individuals who died after infection (either from Covid-19 or a different cause) were predominantly negative except for infections in the Alpha and Delta eras.3

In contrast with the monkeys, a preprint appearing last month by Krishna, et al. fails to find any RNA in the brain after infection in mice:

Krishna, et al. “Impact of age and sex on neuroinflammation following SARS-CoV-2 infection in a murine model.” biorxiv.org

Notably, no viral RNA was detected in the brains of infected mice, regardless of age or sex. Nevertheless, expression of IL-6, TNF-α, and CCL-2 in the lung and brain was increased with viral infection. An unbiased brain RNA-seq/transcriptomic analysis showed that SARS-CoV-2 infection caused significant changes in gene expression profiles in the brain, with innate immunity, defense response to virus, cerebravascular and neuronal functions, as the major molecular networks affected. The data presented in this study show that SARS-CoV-2 infection triggers a neuroinflammatory response despite the lack of detectable virus in the brain.

Overall, it remains the case that the danger of viral invasion of the brain appears lower for SARS-CoV-2 than for plenty of everyday viruses we already have dealt with forever; and the brain-fog problem seems more likely to be related to inflammation given that most people recover quickly, and may not be a response to the spike protein but to other weapons in the virus’s extensive arsenal. Not much needs to be added to my lazy coverage of Rudy Tanzi’s remarks a year ago:

If you derived value from this post, please drop a few coins in your fact-barista’s tip jar.

Andrewes, 1953, “Epedimiology of Influenza.”

Shope, 1958, “Influenza: history, epidemiology, and speculation.”

Hirschbühl, K, et al. “Viral mapping in COVID-19 deceased in the Augsburg autopsy series of the first wave: A multiorgan and multimethodological approach.” PloS one. 2021;16(7):e0254872.

Hirschbühl, K, et al. “High viral loads: what drives fatal cases of COVID-19 in vaccinees? - an autopsy study.” Mod Pathol. 2022;35(8):1013-21.

Märkl, B. et al. “Fatal cases after Omicron BA.1 and BA.2 infection: Diffuse alveolar damage occurs only in a minority – results of an autopsy study.” medrxiv.org

Kevin McKernan (you know, that guy with more than 20,000 citations) suggests that "20-30% of COVID deaths have aspergillosis. COVID isn't the issue, immune suppression is"

https://twitter.com/Kevin_McKernan/status/1703026695748653507

Regarding not having a control group in the "VAIDS" study: the authors explained that it would be "unethical" to have a control group (crazy, I know)

> Limitations include the inability to include an unvaccinated control group due to the ATAGI recommendation for all children aged 5 to 11 years to receive the BNT162b2 vaccine. It was unethical to randomise children into an unvaccinated, placebo or delayed vaccination group, given that ATAGI recommended the BNT162b2 vaccine for the age group of interest and that Melbourne was experiencing a surge in COVID-19 cases in the community during the study period.