The Natural Immunity Illusion Illusion, Pt 1

A visit to the front lines, in the battle to abolish natural immunity

But seest Thou these stones in this naked hot desert? Turn them into bread, and mankind will run after Thee like a flock, grateful and obedient, although always trembling, lest Thou withdraw Thy hand and deny them Thy bread.1

The counter-attack against natural immunity to SARS-CoV-2 is here. Like the blessed future king who slayed the much-maligned warrior-giant of the Philistines, the hero arising to hurl the stone on behalf of the Kingdom of Medicalized Immunity begins its name with the letter D.

2Before we wade into a break-down of this assault on nature, we may comment that it seems strange to posit that natural immunity is Goliath - the invincible, dominating god-among-men - in this battle, as the scientific and expert consensus relayed to us by the media throughout the Pandemic™ has been squarely and solidly nonplussed on the matter.3 Whether we could expect that individuals who recover from Covid-19, however that event is defined, will be protected from experiencing the event again, has been and still is being cast as “unclear,” and “unknown,” and “not well described;”4 in rather the same manner as one could observe that whether the grocery store will be out of broccoli at any given moment is “unclear,” and “unknown,” and “not well described.”

This radical manifestation of epistemic caution emerged from who-knows-where, but was quickly elevated to the status of fact™ by a media reward-system which seeks out from our expert class precisely those statements which make viewers dependent on tuning in to hear the same expert speak again tomorrow. The trope thereafter entirely defined media discussion of the risks faced (and presented to others) by those who have recovered, with the explicit implication that recovery from SARS-CoV-2 is not a license to cease one’s year-long hyper-adherence to the various “temporary” mandates of our governments. We may say radical, because on other matters - those which were not pertinent to the artificially-constructed consensus of the “scope of the emergency” - our experts have been ostentatious in their display of inflexible thinking, even where flexibility in the name of caution could be expected to potentially save lives: Here we may list the flatly moronic, ossified convictions that coronaviruses are not “airborne” because they are “too big,” and that non-antiviral drugs cannot be effective in treating a disease whose pathology was never primarily virological.5

But one must be careful not to make too much of the relationship between categorically peculiar expert epistemic ambivalence, media slant, and the submission of the entire population of the Earth to Orwellian government dictates. Even when there was every reason to expect that those who had recovered were not in danger and were not a danger to anyone else, the experts were obviously just being “cautious.”6

Yet even if our experts and the media continue to insist that, gosh, there is simply no telling if the Goliath of natural immunity to SARS-CoV-2 will ever arrive, his footsteps have been thundering across the battlefield throughout the new year. The import of his arrival is certain, and clear: the radical, unfounded, and politically caustic speculations about the danger of reinfection have been refuted.

The lie that “we don’t know” whether infection with SARS-CoV-2 confers immunity is dead; or at best, a zombie.

June: Look on Our Works, Ye Virus, and Despair!

A dozen or so studies have emerged, from December to the present, suggesting that those who recover from an encounter with SARS-CoV-2 are protected from reinfection. Additionally, they suggest that merely scoring positive for SARS-CoV-2 in a PCR-test implies meaningful future protection. Suggestion One accords with everything we think we know about immunology, and is what should have been expected to happen. Suggestion Two is a nice surprise - though, there were already hints that PCR-testing may not be the false-positive-monster it has been made out to be.7

All of these relevant studies, critically, (attempt to) measure actual rates of observed reinfection. They must do so. The entire radical premise which they seek to test - that immunity to SARS-CoV-2 is short-lived - demands that standard immunological expectations be nullified, including the expectation that testing positive for antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 implies functional immunity to SARS-CoV-2. Even though, in the real world, where any prediction that accords with our prior observations of reality by definition is implied, testing positive for antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 implies functional immunity! It has done so from the very start!8

9Insisting otherwise has always been nothing more than a lie used to justify a risk assessment that erases the boundary between known unknowns and unknown unknowns. Under that lie - that functional immunity is a known unknown - those who test positive for antibodies have been treated as vulnerable to a threat that did not in fact exist, and could not reasonably have been expected to exist; they have been deprived of relief from our mass governmental restrictions, for no reason; they have been pressured and deceived into being vaccinated, for no reason and at a risk which is itself a giant glaring known unknown.

Very well, then. Let us see what has been revealed by this attempt to disprove what was never even likely to be true.

The PCR Test Vindication

Several of the studies rely heavily on PCR testing. In Austria, for example, a retrospective analysis of the national epidemiological reporting system found that among 14,840 PCR-confirmed “survivors” at the beginning of September, only 40 had tested positive as of the end of November, despite a rather large autumn wave which peaked ~November 12.11 This gave them a tentative (because it is only based on PCR testing) case rate of 0.27%, compared to 2.85% for the rest of the population during that same time.

Another retrospective analysis of patients tested at a health center with locations in Ohio and Florida found a more ambiguous result - but this was primarily because it was not using data about overall population or patient cohorts:12 Previously PCR-confirmed patients, who later sought another test, were compared with the non-previously-confirmed “other” patients who sought a test during the same time; and the “other” patients who sought a test in the first 90 days after the “previously-confirmed” cutoff date were excluded from the calculation of the rate of infection among “others,” even if they tested positive. This stands in contrast with the Vienna study, where reinfection case-rates where calculated relative to the total population of previously-infected. Even with this double-whammy of selection bias and cohort handicap, the authors found that “Protection offered from prior infection was 81.8%.”

And in last month’s watershed, but backwards-titled “Necessity of COVID-19 vaccination in previously infected individuals”13 - in fact a direct assault on the prevailing paradigm that those who have already had an encounter with SARS-CoV-2 should be vaccinated - PCR-confirmation as a proxy for functional immunity was put through the boldest trial possible: Among the 2,579 employees in the Cleveland Clinic Health System who had tested positive at any point before November 5, not one tested positive between mid-December (when vaccination became available, and in the middle of the winter wave of cases) and mid-May. This includes the 1,359 who were still unvaccinated or not yet fully vaccinated at the end of those five months.

Meanwhile, among the other 49,652 workers (who had not previously tested positive by the November 5 cutoff), 2,139, or 4.3%, tested positive in the trial period.14

The Necessity Study’s implications are limited in important respects: The Cleveland Clinic Health System was not, during the study duration, performing scheduled-screening PCR-tests. The other studies (including those considered below) suggest that screening likely would have revealed some number of asymptomatic reinfections.15 Additionally, the final “unvaccinated” groups would have included employees who had begun vaccination, but were not yet at the 2nd dose + 2 week mark. And yet, the implications are nonetheless groundbreaking in another, even more important respect: Because 25% of the previously-infected cohort includes workers who PCR-tested positive before mid-June 2020, and none of this cohort PCR-tested positive again between December to May 15, 2021, this study pushes the yet-knowable window of observed, functional natural immunity to the 1 year mark.16

To support our contention that natural immunity is the Goliath in this battle, and that individuals who have been previously infected with SARS-CoV-2 may safely forgo vaccination, we may string-quote the conclusions of the three studies reviewed above:

Protection against SARS-CoV-2 after natural infection is comparable with the highest available estimates on vaccine efficacies.17

Prior infection in patients with COVID-19 was highly protective against reinfection and symptomatic disease… patients with known history of COVID-19 could delay early vaccination to allow for the most vulnerable to access the vaccine and slow transmission.18

Individuals who have had SARS-CoV-2 infection are unlikely to benefit from COVID-19 vaccination, and vaccines can be safely prioritized to those who have not been infected before.19

20The critics, as they say, are raving. The studies above are strongly supportive of the conclusion that natural immunity to SARS-CoV-2 is real. As well, the high level of correlation in every study between previous receipt of positive PCR-test, and later observable non-receipt of positive PCR-test, suggests that PCR-tests are in fact an accurate detector of asymptomatic encounters with SARS-CoV-2 - even in different countries with potentially different protocols for cycle counts, etc. It is unreasonable to imagine, for example, that only a handful of the 14,840 previously-positive-tested Austrians should have tested positive during the autumn wave, unless their previous positive PCR-test signified something that conferred later unlikelihood of positive: Namely, an actual encounter with SARS-CoV-2 leading to natural immunity.

This finding is of great significance to how we evaluate the definition of a Covid-19 “case” and how we estimate prevalence of population-wide immunity going forward. That sure seems like pretty big news!

But don’t touch that dial. Coming up, after a word from our sponsor, it’s the antibody studies.

Today’s essay is sponsored by: Coffee pots.

Unglossed thanks coffee pots for their support.

The Antibody Test Vindication

The PCR studies are not, in fact, “big news.” Because, as it turns out, the first across the finish-line of the reinfection studies, out of the Oxford University Hospitals / NHS research hospital and published online two days before Christmas, had already accomplished much of what the PCR studies would reinforce later. That’s right: By the end of December, the myth that SARS-CoV-2 is “immune” to human immunity had already been destroyed.

This study, by Sheila Lumley, et al., is titled: “Antibody Status and Incidence of SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Health Care Workers.”22 Although the implications were Earth-shattering (or rather, de-shattering) at the time, the reaction to its publication was mild and, once again, ambivalent. The two v’s, vaccines and variants, continued to dominate medical journal and media attention throughout the winter and spring. Yet once again, the refusal to speak Goliath’s name does not erase his footsteps from the soil. And as the OUH study has now been given support (as well as some nuance) by a similarly-designed effort out of Northern Italy, published last week, this is an appropriate occasion to give the results their due.

In this brilliantly-designed work, the authors strictly measured the difference in outcome between workers who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, and those who did not. This excludes from the test group any possible individuals with functional immunity, such as from prior asymptomatic infection, who did not test positive in the authors’ custom-calibrated antibody test. The design necessarily leaves unanswered, as well, whether testing positive for antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 antigens can and might often result from generic immune familiarity with coronavirus, suggesting that this virus is indeed not so “novel” at all.

But that’s the beauty of the design: It doesn’t need to answer those things. In fact, by skipping those questions altogether, it cuts through the entire cloud of artificial radical uncertainty spun around SARS-CoV-2, and reveals a potential fortress of certainty hidden within, one which towers over its would-be infiltrator. What the study asks, is merely:

If someone tests positive for antibodies, are they likely to get Covid-19 or not?

We only need to discover if we, humanity, are in fact within this fortress.

From here, summing up the key result is trivial: Among the 1,265 workers who were sorted into the antibody-positive group, only 3 went on to score positive on a PCR test over the subsequent six months. One of those appears to have been a false positive. The other 2 were asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic, as well as confirmed infected by a rapid (additional) raise in their antibody test values, indicating learned immunity functioning as expected.

That’s it. That’s immunity to SARS-CoV-2.

The authors go on, nonetheless, to do various maths, and flesh out their conclusions.23 We will substitute their use of “person-days” and reduce the triple-categorization of the positive antibody cohort to allow the results to conform to the other studies considered in this essay.

Among 1,265 workers who were counted “seropositive” in the study, meaning they tested positive for IgG antibodies sensitive either to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein or to the nucleocapsid, 3 tested positive within the 6 month time-frame. This leads us to a reinfection rate of:

3 / 1,265 = .2%

Among those 11,364 who tested as “seronegative” - detected levels of antibody did not meet the authors’ custom threshold - 223 went on to test positive during the study:

223 / 11,364 = 2.0%

Presumably, at least some of the seronegative cohort’s PCR hits would have been false positives; and the authors acknowledge that this cohort overall was being scheduled-screening-tested more frequently than the seropositive cohorts. On the other hand, one of the 3 seropositive workers to test positive was obviously a false positive, as will be discussed below (however, the rate still rounds to .2% even with that adjustment).

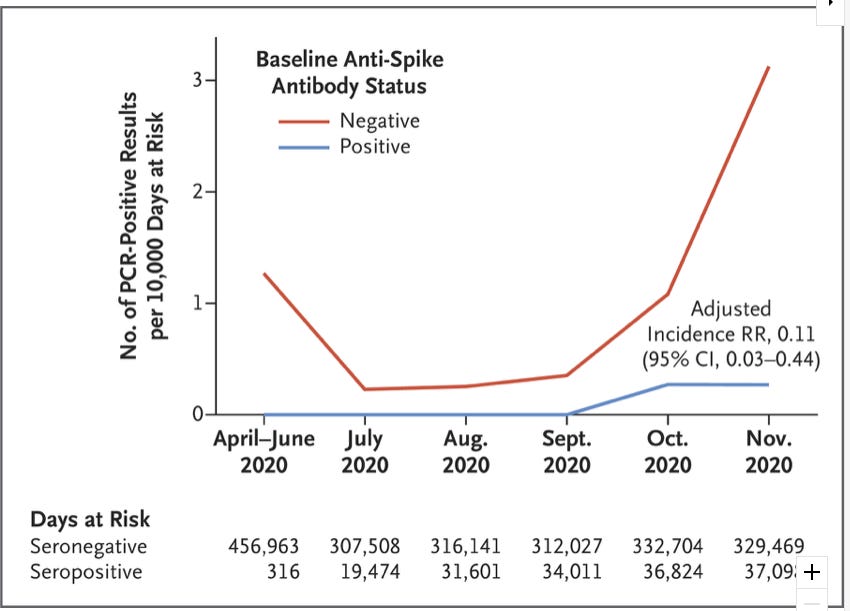

Additionally, and as mentioned, we don’t know how many within the seronegative group were also functionally immune, despite batting for the underdogs. 223 positive PCR tests - a 2% case-rate - among the seronegative group is a rather impressive result on its own (better than the rate for Austria’s general population in the shorter, but overlapping timespan above). That the control-group did so well, of course, is only all the more reason for cheer for natural immunity - yet it diminishes the numerical superiority of the outcome for the seropositive group. Critically, however, the OUH study as published in December stuck with its subjects through the England’s autumn wave. It is clear from the resulting calendar of results, that had the study been limited to either only the late spring or autumn, the numerical difference in outcomes between the two groups would be even more dramatic. From the study (plotting out the authors’ calculation of positive tests per person-days; here the false positive is included and represents 50% of the blue line value, which is limited to the performance of spike protein seropositive workers):

As England experienced an even larger wave of “cases” in the late winter, such additional data might have yielded a far more numerically-impressive disparity in results.

Moreover, we can, if we wish to, project out a gradual rise in reinfection in the high-immunity seropositive group through winter, and 2021, without contradicting our conclusions. The study, once again, was testing against the proposition that immunity to SARS-CoV-2 does not work like normal immunity. It does not support that proposition. And projecting that reinfection increased gradually, after the window of observation, merely accords with the conclusion that immunity to SARS-CoV-2 works normally: Which is to say, exceptionally well. In fact, the strongest evidence for that conclusion comes from the two reinfections.

The authors plot out the test results of the three official reinfections - the subjects who tested positive for either anti-spike or anti-nucleocapsid antibodies upon enrollment,24 and went on to earn a strike on PCR. “HCW 2,” in the middle, is the obvious false-positive:

We can conclude HCW 2 is a false positive both because PCR tests returned negative two and four days after the positive, and because antibody levels were not elevated, as would occur with re-exposure to SARS-CoV-2.

Which is exactly what happened with HCWs 1 and 3. Both reinfections are gratifying demonstrations of conventional immunological wisdom. In HCW 1, a low response to the spike protein did not seem to equate to an unfamiliarity with SARS-CoV-2 (although HCW 1 scored near zero on the anti-spike assay, a higher “exposure” test might have revealed detectable antibody response; however, the calibration suggests the exposure should have been high enough, corresponding with the high sensitivity rate). HCW 1’s positive nucleocapsid antibody test during study enrollment did not correspond with a previous infection with SARS-CoV-2 as confirmed by either symptoms or PCR testing. By all appearances, HCW 1 did not actually previously encounter SARS-CoV-2. Thus, upon “reinfection” 160 days after the positive nucleocapsid antibody test, HCW 1 experienced a mildly symptomatic case followed by elevated nucleocapsid antibodies and the arrival of previously missing spike protein antibodies.

In other words, it is reasonable to imagine that HCW 1 experienced SARS-CoV-2 exactly like a regular coronavirus.25 It is reasonable to imagine that this is how most people experience SARS-CoV-2, regardless of prior direct exposure. It is reasonable to imagine that this is why so many “cases” are asymptomatic or mild (HCW 3’s original infection was not confirmed as SARS-CoV-2 by a PCR Test, which may mean it predates the occasion of her receiving a test; her reinfection was asymptomatic).26 It is reasonable to imagine these things, because they accord with everything we already believed we know about immunology.

The Antibody Test Vindication Refutation?

There is one nuance to address, however, before we move on to the counter-attack of the Delta variant study: Does the new antibody study from Northern Italy support or complicate our conclusions so far? The answer, is both.

This venture, posted online on July 6, but also based on observations up to November of 2020, appears to repeat the format of the OUH study, but broadly observe a higher rate of reinfection:28

During the 6-month survey, 1.78% seropositive subjects developed secondary SARS-CoV-2 infection while 6.63% seronegative controls developed primary infection… Mild symptoms were reported in 11 [of the] 24 (45.8%) [of the 26 reinfections among 1,460 seropositive workers for which symptom data was available] vs 279 [of the] 391 (71.4%) [of the 540 infections among 8,150 seronegative workers for which symptom data was available]… while the other subjects were asymptomatic.

Firstly, even this ulimately reaffirms the answer to the question posed by the construction of both studies: If someone tests positive for antibodies, they are unlikely to get Covid-19 (the disease which follows infection from SARS-CoV-2), because immunity to SARS-CoV-2 works normally.

Further, reframing the results in terms of (mildly) symptomatic cases (to which the term “Covid-19” still does not really apply), gives us:

Seropositive mild reinfections: (.458 x 26) / 1460 = .8%

Seronegative mild infections: (.714 x 540) / 8150 = 4.7%

This is decent.

Yet an examination of the manner used to classify seropositive subjects in the study reveals an additional interesting and semi-accidental nuance. The authors do not go out of their way to highlight this possible flaw, perhaps as to do so would necessarily create the impression that they were trying to skew their own results. The discrepancy is in their antibody-testing standard.

In the OUH study, subjects were divided based on scoring positive or negative for antibodies on two custom-calibrated ELISA-format tests. (A thorough guide to ELISA is included in our examination of the study from Singapore.29) The OUH study further provides a thorough discussion (in the appendix) of how their antibody tests were calibrated, and the high sensitivity and specificity ratings they achieved - meaning that any tests of equal sensitivity / specificity can be expected to measure the same degree of immunity that they measured.30

The Northern Italy authors also created a custom-calibrated ELISA antibody test for detecting antibodies to the spike protein, which also had high sensitivity / specificity ratings: But due to short supply, this was not used to sort their subjects into the seropositive group. Instead, they sorted based on the results of the commercial DiaSorin “Liason SARS-CoV-2 S1/S2 IgG” assay.31

But since they were at least able to use their own, custom test at the Pavia hospital location, where 3,762 of the workers involved in the study worked, they tried their custom test on the original sera of all seven of Pavia’s seropositive “reinfection” subjects, as well as a sample of thirteen seropositive non-reinfection subjects, and found a clear difference in specificity between their custom test and the Liason. While the non-reinfection sample of 13 did not find any “false positives” (though it did catch three borderline measurements), five of the seven “reinfections” would have been sorted to the seronegative group (and one of the other two was borderline), had the authors used their own test to sort workers at Pavia.32

Thus, for these 3,762 workers, if we recategorize our groups based on the authors’ custom test (which resembles the OUH custom test in sensitivity / specificity) we achieve the following alternate result (while generously shifting 74, or 3/13 of subjects out of the seropositive cohort to reflect the likely non-reinfections that would have landed in the seronegative group) when we compare reinfections measured as positive PCR-tests, the original metric of the study:

Seropositive reinfections: 2 / 247 = .81%

Seronegative infections: 224 / 3,515 = 6.37%

Thus, at least in the Pavia hospital partition of the Northern Italy study (which alone was 1/4 the participant size of the OUH study) the latter’s result has been closely replicated. The seronegative/seropositive ratio of PCR-confirmed case rates at OUH (with or without the false positive) was:

.002 / .02 = .1

At Pavia, using our reconstruction, it was:

.0081 / .0637 = .13

The Antibody Test has been vindicated, again, and expanded upon. Testing positive for antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 with a sufficiently high-specificity test indicates strong functional immunity. Testing positive for antibodies with a lower-specificity test indicates one’s high position in the spectrum of protection that prevails in a given population. Therefor:

Natural immunity to SARS-CoV-2 works exactly as it should.

Countries could safely have used antibody tests to reopen society all along.

Continued in Part 2…

Constance Garnett’s translation. However, I have substituted “naked hot desert” for her odd choice of “parched and barren wilderness;” “flock” where she uses “flock of sheep;” and “although always” for “though forever.”

Both meanings of “nonplussed” may be applied.

Here I am quoting the introductions of two of the studies cited below, as well as one based in Denmark which is not included in this essay. Regarding that study, it has the same “sought testing” selection bias as the second study included in this essay to represent the range of PCR study results, “Reinfection…” by Sheehan M. et al.

To this might be added the initial admonition against masking, which was so infamously reversed. As odiously paternalistic and socially and spiritually corrosive as masking is, the question of what a “radically epistemically cautious” epidemiological recommendation would have been yields the answer of recommending masking. And there is no more excellent device to promote and reify submission to the Hobbesian Leviathan, or, in the double-speak of our Inquisitors, “show that you’re taking the virus seriously,” than masking. If masking was initially mis-categorized as being irrelevant to the potency of the artificial consensus of the scope of emergency, only to be correctly re-categorized as relevant, this explains the simultaneous alteration in epistemic categorization within the consensus of the experts: It begins as an orthodoxy, and ends as an uncertainty (which therefor must always prompt a default to maximum caution).

There, that’s better. No more of that dreadful, “thinking” stuff.

Siemens, for example, reports that their SARS-CoV-2 RBD antibody detecting assay returns a positive for 188 out of 195 samples 21 days after a positive PCR test. See p. 3 of the spec sheet (pdf) at the bottom of https://www.siemens-healthineers.com/cz/laboratory-diagnostics/assays-by-diseases-conditions/infectious-disease-assays/cov2g-assay (They presumably have much broader figures for their testing outcomes available, possibly published elsewhere.)

Though the vogue to say otherwise has been eagerly taken up by the manufacturers of antibody tests. Why should they mind, if the new version of faceless War-on-Terror server-farms filled with vast, incomprehensible troves of surveilled electronic communications is an archipelago of faceless med-labs filled with vast, incomprehensible troves of test results? Government and business-leaders continue to cower in awe of big data as if it was the next atomic bomb, despite a conspicuous lack of concrete results.

(index link anchor)

(index link anchor)

Pilz, S. et al. “SARS-CoV-2 re-infection risk in Austria,” European Journal of Clinical Investigation.

Sheehan, M. et al. “Reinfection Rates Among Patients Who Previously Tested Positive for Coronavirus Disease 2019: A Retrospective Cohort Study,” Clinical Infectious Disease. The analysis for this study effectively applies to the Denmark study in footnote 4.

Shrestha, N. et al. “Necessity of COVID-19 vaccination in previously infected individuals,” medrxiv.org

(I have made a correction here from an original figure, to reflect that the not-yet vaccinated should be considered part of the initial risk pool for not-previously infected workers.)

Employees were categorized as vaccinated 2 weeks after their second dose. “Unvaccinated” in the results therefor includes those workers who were between their first vaccine dose and the second dose + 2 weeks mark, either at the time of infection or at the end of the study.

Overall results, math my own:

(Some employees were removed mid-study due to termination or receipt of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine: * represents the resulting margin of error of 0 - 100% in given denominator.)

Previously PCR-confirmed-infected reinfection rate: 0 / 2579 = 0%

Completely Vaccinated by day 60 reinfection rate: 0 / 332

Completely Vaccinated between day 60 - 80 reinfection rate: 0 / 594*

Completely Vaccinated between day 80 - 120 reinfection rate: 0 / 95*

Completely Vaccinated between day 120 - 140 reinfection rate: 0 / 199*

Unvaccinated / Incompletely Vaccinated by day 150 reinfection rate: 0 / 1265

Mid-study dropouts reinfection rate: 0 / 94

Not previously PCR-confirmed-infected infection rate: 2,154 / 49,652 = 4.3%

Completely Vaccinated infection rate: 15 / 28836 = 0.05%

Unvaccinated / Incompletely Vaccinated infection rate: 2,139 / 49,652 = 4.3%

Estimated Day 0 - 80 U/IV infection rate in 150-day units: (1620/49652)(15/8) = 6.1%

Estimated Day 80 - 150 U/IV infection rate in 150-day units: (529/21,332)(15/7) = 5.3%

Estimated Day 0 - 150 U/IV real infection rate (1620/49652) + (529/21,332) = 5.7%

The last three values are an attempt to correct for the discount created by the eventual removal of 28,836 not-previously infected subjects from the original pool (into the vaccinated pool). Day 0 - 80 values reflect that most cases were occurring in this period, during the winter; however, the denominator was still very large. Day 80 - 150 values reflect that although fewer cases were occurring, the denominator was already less than half the original size. Per Figure 3, 21,332 not-previously infected employees had not completed vaccination as of Day 80. Although the study does not give a calendar of absolute case counts, I used the proportional plot to estimate a Day 80 multiplier of x (3.84/5.1) for the given total case value of 2,139, and used this to produce the value of 1,620 cases on Day 80. (The plot proportion values, such as the final value of .051, don’t seem to correspond to any of the given populations, so I don’t see a valid way to adjust for difference in population between Day 80 and 150). Figure 3 as retrieved on 2021/07/15:

Lastly, a crude attempt to weight the Day 80 - 150 rate of NPI-V positivity in 150-day units, and calculate the corresponding case value (percentage x population) benchmark among the PI-unV population of 1,265 (within which the actual case value was 0):

(15/28836) x (15/7) x 1265 = 1.41.

Screening testing was also not being done before the beginning of the study. Thus the “previously infected group” (PCR-confirmed cases dating at least 42 days before the vaccination rollout / study start date) probably includes fewer asymptomatic cases than some other studies (only 12% of the “previously infected” did not have a listed symptom onset date; however, for those that did have a symptom onset, recording was potentially more thorough than in general populations).

Upon this point the authors are more conservative, but still strident:

This study was not specifically designed to determine the duration of protection afforded by natural infection, but for the previously infected subjects the median duration since prior infection was 143 days (IQR 76 – 179 days), and no one had SARS-CoV-2 infection over the following five months, suggesting that SARS-CoV-2 infection may provide protection against reinfection for 10 months or longer.

Pilz, S. et al.

Sheehan, M. et al. Note the conspicuous use of “Covid-19” in this quote and of (in the study title) “Coronavirus Disease 2019,” when all that was being measured was positive PCR-testing for presence of SARS-CoV-2. “Covid-19,” properly defined, is the severe reaction experienced by a minority of individuals who encounter SARS-CoV-2.

Shrestha, N. et al.

(index link anchor)

(index link anchor)

Lumley, S. et al. “Antibody Status and Incidence of SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Health Care Workers,” New England Journal of Medicine.

The authors conclude that the seronegative group experienced 1.09 positive tests per 10,000 person-days. The group of 1,265 who tested seropositive against the spike protein specifically, the rate was 0.13 per 10,000 person-days. Presumably, at least some of the seronegative cohort’s PCR hits would have been false positives; and the authors acknowledge that this cohort overall was being scheduled-screening-tested more frequently than the seropositive cohorts. On the other hand, half of the .13 per 10,000 person-days of the spike-protein seropositive cohort is the aforementioned false positive.

Originally seronegative employees were moved into the seropositive group if their post-recovery antibody tests qualified. (Only 88 PCR-confirmed originally-seronegative employees were moved; presumably the others had not yet made the recovery timestamp by the end of the study, given that most of the PCR-confirmed cases were in November.) Their time in each group is weighted to produce the resulting person-days denominators. The significance of this, is that we know that no one in this crossover group went on to test positive again during the study interval; it’s not as significant a result as the original seropositive cohort, but it’s significant compared to if any in the crossover group had tested positive.

All three incidences of seropositive employees receiving a positive PCR-test, thus, were from those who had antibodies during original enrollment. “Days to reinfection” for HW 3 is from the onset of symptoms during primary (original) infection. From the study:

However, more frequent serology results, especially in the days immediately after the positive PCR test, would better support this conclusion.

A future essay will address the controversy of “asymptomatic spread.”

(index link anchor)

Rovida, F. et al. “Incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in health care workers from Northern Italy based on antibody status: immune protection from secondary infection- A retrospective observational case-control study,” European Journal of Clinical Investigation.

The OUH authors’ calibration may or may not match existing commercial SARS-CoV-2 antibody tests, given the Liason threshold disparity. However, there is ample room to iteratively recreate the study with higher-sensitivity, lower-specificity antibody tests, to attempt to find the lower limit of detectable antibody concentration which corresponds to functional immunity (even if we define functional immunity as greater mildness of symptoms, as with the Northern Italy study). Commercial antibody test manufacturers have put a great deal of work into calibrating their tests to correspond with recent lab-confirmed (PCR) infections. Very little work, if any, is done to look for calibrations that correspond with background immunity, such as seems to have been accidentally observed with HCW 1.

From the Northern Italy study; annotation to be added later. A represents the results of the test which was used to actually select seropositive subjects for the final results. B represents the results of the authors’ custom-calibrated ELISA antibody test applied to a sampling of the seropositive subjects who did not go on to receive a positive PCR test, and all 7 who did: