In response to discussion in the comments of my last post, I decided I should offer a defense of the general idea of SARS-CoV-2 being possibly natural. How could it be!? Below we examine how.

First, a brief review: In the prior post, I noted that I find there to be no non-circumstantial evidence favoring an origin from the Wuhan Institute of Virology, which is damning for “muh lab leak” in light of the fact that there is no apparent explanation for the lack of direct evidence in what was published by WIV before 2020, which only leaves baseless conjecture that the lab was running a separate, deliberately clandestine research project, perhaps under the auspices of the Chinese Military. (Were they? How could anyone say, there is no evidence of it.)

I further noted that I do not believe natural origin is likely, simply based on the absurd coincidence of the virus emerging in Wuhan. In other words, of the circumstantial evidence, I find this fact to argue compellingly against a natural origin — it simply wasn’t a very likely accident, given that Wuhan’s markets only represented 1/100,000 of China’s wildlife trade.1 None of the other circumstantial evidence strikes me as compelling. Finally, the synthesis of the two points above is that I think the virus was released in Wuhan on purpose.

Defending the biological plausibility of SARS-CoV-2 being natural was not the remit of that post, and so will be undertaken here. I will start with the question of the virus’s fitness in humans, and then address the Furin Cleavage Site, an order based on how interesting I find the problems.

i. Resolving the fitness problem: A frequent visitor

Again, for those who skipped the introduction, I do not think natural origin is likely, based on the virus’s appearance in Wuhan as opposed to somewhere else; the point of this post is to show that natural origin is otherwise not so implausible as has been portrayed.

Introduction to the problem

While the recent scientific cult of “pandemic preparedness” has spent the last decades preconditioning the masses to expect a novel virus to jump from wild animals and infect all of humanity, and continues to do so today, it is in fact the case that SARS-CoV-2 was as far as we know unprecedented.

This lack of precedent stems from the novelty of cell culture (which makes establishing serial passage of viruses easier, and allowed for the first identification of a coronavirus in 19642), as well as gene sequencing. In short the “pandemic preparedness” cult has been urging humanity to be afraid of a type of disaster that has allegedly always been a threat despite only recently becoming observable, and (before SARS-CoV-2) never happening except with flu.

Is HIV new?

Before discussing flu, an objection might be raised that HIV represents a textbook crossover pandemic. However, it should be questioned whether HIV was ever an ape virus making a new home in humans, as opposed to an ancient, human-adapted virus that simply went unnoticed until the sexual revolution and the advent of needles. In brief defense of the latter theory I will note that HIV has many clades. In fact there is as much phylogenic diversity in HIV as there are in related simian viruses, which can’t be explained by a recent cross-over resulting from one incident of over-friendly man-animal relations.

Are flu pandemics “novel”?

Influenza A virus pandemics are sui generis in that they have been fairly well tracked since the 1930s thanks to the virus’s amenability to passage in eggs, and in that they are semi-regular. When H2N2 and H3N2 emerged in 1957 and 1968, older people (alive in the 1880s and 1900s) already had antibodies, because these species of the flu spike genes were just crossing back over from the avian reservoir, where they meanwhile hang out in relative evolutionary stasis, waiting for humans to stop being immune to them. Likewise, when “swine flu” emerged in 2009, it was only re-introducing a vintage model of the H1 spike protein that had already proved its fitness in 1918, but to which few people still had strong immunity (the H1 spike in swine flu remained unchanged from that time because pigs are slaughtered regularly, so there is no immune pressure). More on this topic is available at my chronology of early flu research.

In other words, because flu is semi-regular, flu pandemics do not introduce “novel” viruses (only “new to you” viruses), and so flu is not a precedent for a bat coronavirus emerging from nowhere to be well-suited to human transmission (relative to viruses that emerge and die out easily). Flu comes (when we have lost prior immunity) and goes (when it runs out of possible mutations to evade immunity).

Has a coronavirus pandemic occurred in anything like recent history?

Lastly, one may claim that human coronavirus OC43 offers a precedent for SARS-CoV-2, based on research and news reports that claimed it was in fact behind the 1889 flu pandemic.

However, it turns out that the genetic evidence for that claim was based on mistaking cell culture mutations for wild virus mutations; OC43 has probably been in humans for a long time. For more, see my refutation of the OC43 pandemic theory.

Summary: SARS-CoV-2 was seemingly unprecedented

Even in an article steelmanning the case for natural origin, I will acknowledge that SARS-CoV-2’s fitness in humans is prima facie an argument in favor of an engineered origin. Only, it is not conclusive or overwhelming.

Additionally, as noted in my refutation of the OC43 pandemic theory, there are some inconsistencies in symptoms and mortality experienced in 1891 that suggest a virus other than flu may have generated a lower-scale, slower dispersion of respiratory illness. This anomaly may be considered perhaps the only potential precedent for SARS-CoV-2, but the phenomenon took place in the prehistoric age before cell culture, returning us to the original problem.

Solution: SARS-CoV-2 may be a regular visitor, like flu

Consider, however, what it might look like if SARS-CoV-2 is like flu: A regular visitor from an animal reservoir which periodically finds its way into humans, only to run through immune-evasive mutations and then fade away. Of course, we have not yet seen the virus fade away, but in a hypothetical scenario when it does so, one could suppose that future humans may see a return of a virus closely related to “Wuhan-Hu-1” (but with mutations generated in bats since 2019, rather than a leak of a vintage isolate of human SARS-CoV-2 as is sure to also happen).

If it were the case that the bat reservoir virus that gave us SARS-CoV-2 is (like flu) natively fit or near-fit for human spread, it may have diffused through humanity in the past; and if so we probably wouldn’t have noticed it. Humans in the past were not as old, overweight, and immunocompromised™; simultaneously, they died at a higher rate. These facts are all downstream of the medicalization of sickness and death — keeping the vulnerable alive means you have more vulnerable people.

Therefore in the past, the prime victims of SARS-CoV-2 — those most prone to severe disease — would all have been in the ground. Additionally, the disease itself would easily have been mistaken for all the other rampant respiratory illnesses of the pre-antibiotic era (tuberculosis, etc.). No imaging machines would have revealed the “ground glass opacities” and other features that distinguish the virus; and pathological documentation is a subjective and imprecise activity that doesn’t allow for reliable inference of what killed people in the past.

Certainly overall mortality among younger adults, especially via secondary cardiac and circulatory ills, may have been driven higher by the virus then as it is today, but that “higher” would not have looked as high relative to yesterday’s baseline adult death rates. SARS-CoV-2 is less a plague than an annoying insect; it only looks like a monster when we shrink down our perspective. In the past, occasional illness and death were a normal part of existence (even today, without media hype and medical statistics, it is arguable that we would not have noticed we were ever in a so-called pandemic).

Thus the solution to how a natural virus could emerge from nowhere suited to human transmission and infection is that it is a recurring spill-over from the bat reservoir.

This would mollify my recalcitrant hostility to the premise of the “pandemic preparedness” cult that viruses can just jump from random animals willy-nilly and kill everyone. At best (because history does not record anything besides flu that kills on the same scale of flu), there may be a range of animal viruses that provide the sort of nuisance to human life that SARS-CoV-2 did; only noticeable when we have medicated away all the bigger problems people worried about in the past.

This is also, again, consistent with the idea that a second, non-flu virus swept through the world in 1891, after the 1889 flu (a flu definitely happened in the earlier year, based on later immunity to H2 and H3) — a virus that seemingly resembled SARS-CoV-2, and so may have been a coronavirus (even if not OC43).

The epidemic of 1891, as contrasted with that of [1889/]1890, was said by Dixey (1892) to be “distinguished by its much greater severity, by its comparatively slow rise, its protracted period of high intensity, and its rapid and uniform fall.” The later outbreaks were also characterized by a different age distribution of mortality as compared with the [preceding 1889/]1890 epidemic, and showed a much greater fatality at advanced periods of life.3

ii. Resolving the FCS problem: A genetic “toggle”

Introduction to the problem

Furin trouble now

The gene for the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein includes instructions for a string of amino acids that prompt a common animal protease (a protein our cells make that cuts other proteins) to cut the spike into two parts. Two “common cold” human coronaviruses have similar amino acids at the same place on their spikes; and the feature prevails generally in viral spike genes.

These amino acid strings woo furin (or similar proteases) by being highly basic, meaning that Arginine (R) and Lysine (K) feature heavily. In general “FCS” can describe a viral spike protein motif involving R or K that is putatively thought to promote cleavage, even if furin hasn’t been definitively identified as the operating protease.

Why cut the spike protein? Without cleavage, spike proteins are dumb, over-designed stubs that merely connect to receptors, hopefully resulting in cellular intake in a vesicle. With cleavage, they turn into harpoon guns that have removed their caps, capable of flinging their interior machinery into cellular membranes after connecting to receptors, resulting in fusion with the cell. Since infected cells express spike proteins on their membrane, cleaved spikes can fire into nearby cells to cause cellular fusion. This is thought to not only promote efficient replication but help the virus evade immune responses.

Unsurprisingly cleavage is not a plus for the host. While the human coronaviruses that do not use cleavage seem no more or less mild in childhood infections than those that do, it’s notable that birds and bats seem unbothered by their constant infections with non-cleaving flus and coronaviruses; whereas when avian flu gains a furin cleavage site it becomes deadly to birds and other mammals, i.e. a “highly pathogenic” avian influenza. (Gains how, you ask. That is the point of the solution, below.)

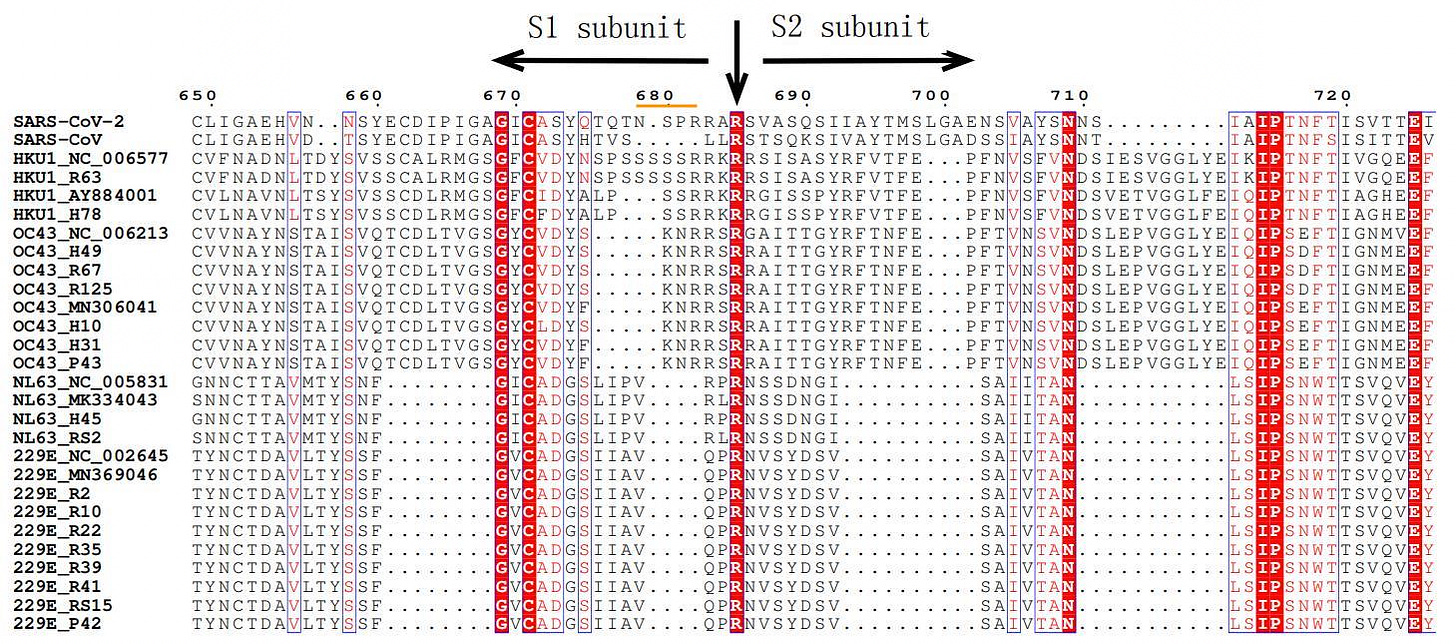

FCS rare in bat coronaviruses (but no longer unknown)

If in humans some coronaviruses have furin cleavage sites and some do not, then the standard lab leaker argument that no sarbecoviruses in bats have been found with an FCS, therefore it is unnatural in SARS-CoV-2, can be dismissed as a mere talking point, a meaningless “gotcha.”

Bats are not required to license their viruses with some federal agency; what we haven’t found today, we can at any point find tomorrow; and we have no very good idea how much of the genetic territory in question is still unexplored. No biological principle argues we should extrapolate from a lack of currently-known exceptions to suppose an impossibility of exception.

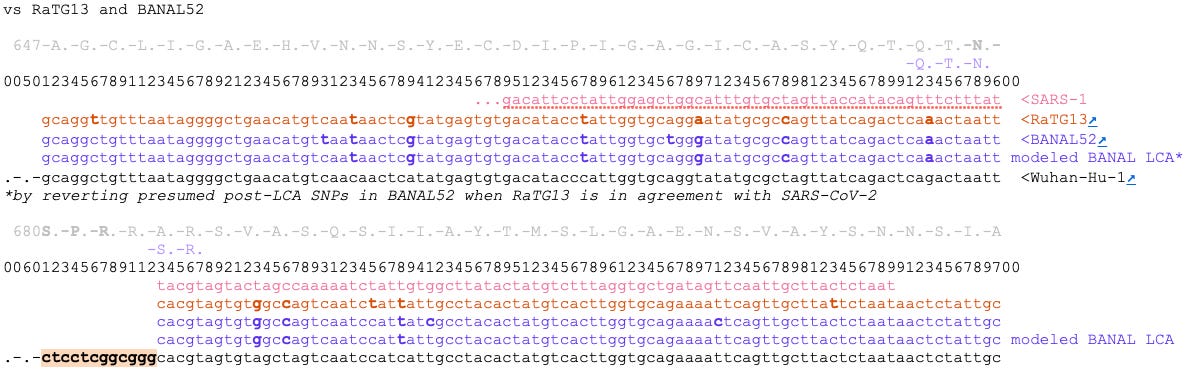

In 2019 no bat coronaviruses were known to have an FCS; recently, members of the subgenus adjacent to sarbecoviruses were found to have FCS’s (red stars below; underline indicates human viruses):

Still, the SARS-CoV-2 FCS is a weirdly cg-rich insert

Beyond the question of have and have-not, is “where got from”?

SARS-CoV-2 not only has an Furin Cleavage Site, but the genes which encode it are an addition to the template — as if some human scientist took the spike gene and wrote in 12 extra nucleotides with a ^. We know that the ^ action took place because multiple relatives of SARS-CoV-2 lack the nucleotides in question. As a simple analogy, if one brother has a sixth finger on his right hand and a dozen other siblings have five, it is a safe guess that the parent was five-fingered, and a mutation added the finger to that one child rather than did a dozen mutations of a six-fingered parent precisely remove it.

It is further evident that the 12 nucleotides responsible for the FCS violate the prevailing genetic “style guide” of SARS-CoV-2 and related viruses. It is unusual for the virus to clump many c’s and g’s together (c’s are rarely followed by g’s; such a sequence in the RNA molecule introduces serial interactions with potential, strong secondary structure effects that the virus seems to prefer to suppress, akin to two bicycle chain links that want to bind to each-other lengthwise).

Once again we can acknowledge this as a prima facie argument for an engineered origin, but not one that is overwhelming.

Solution: Viral spike genes may promote FCS insertion

The problem with using the FCS insert to argue that SARS-CoV-2 is a lab-grown witch is that highly pathogenic avian influenzas are also the product of inserts. In fact, some property of the flu spike gene seems to promote the “random” insertion of genes for basic amino acids at exactly the site that would result in cleavage and higher pathogenicity.

To quote from the 1990 paper:

In addition to the point mutations with the CEC variants SC32 and SC35, in which the enhanced HA [flu spike protein] cleavability led to striking changes in their biological properties, an insertion of nine nucleotides, CGGAGGGGG, was found in the region of the cleavage site (Fig. 5). With SC32 the insertion corresponds to the amino acid sequence Arg-Arg-Gly [RRG], which is directly adjacent to the NH2-terminal Gly of HA2 [the bottom half of the spike protein left after cleavage].

How can a virus “self-engineer” in this fashion? In genetics, information is being read and copied by physical machines, but certain information can prompt errors in the process, the same way an unreliable ink jet printer might struggle with certain clusters of letters. But all mistakes are potential regulators of expression. We know coronaviruses use “mistakes” in our native reading-machine proteins (ribosomes) and its own copy-machine protein (the rdrp) to regulate gene expression in two critical ways. Our ribosomes sometimes “randomly” skip over the first in-frame stop codon in the complete viral RNA molecule, so that for every 2 “Orf1” proteins before the stop, there are 1 of the proteins after (numbers arbitrary here). And when the coronavirus rdrp is copying the same molecule, molecular RNA promoters force it to skip from just before little genes at the end of the negative strand to the very beginning, stitching together the functional messenger RNAs that code for spike and other proteins. Compared to these sophisticated gene regulation maneuvers, exactly how implausible is a natural, built-in FCS insertion promoter?

In the example of flu above, it would seem that something about the genes near the division of the spike (HA) segments 1 and 2 prompts the protein responsible for copying flu genes (the rdrp) to “mistakenly” insert a bunch of _gg’s (either cgg or agg spell arginine).

In the wild, avian influenzas do not have FCS’s. But this could merely reflect that the “mistake” of inserting an FCS, when it happens in avian flu, is selected back out of the gene pool.

The same could prevail for bat coronaviruses, including the ancestor for SARS-CoV-2 — the genes nearby the ideal location for an FCS promote an error in the process of copying that results in the insertion of _gg’s, but typically the resulting virus is selected out of existence due to being too pathogenic in bats. However, this “bug” in the software helps bat coronaviruses occasionally find glory and profit in other mammalian hosts where the FCS is an advantage.

We can note the interesting fact that when SARS-CoV-2 is passaged in cell culture, it often loses the insert responsible for the FCS. Thus, there would seem to be a genetic promoter for the virus’s rdrp to delete the insert. This, along with the example of flu, means it is no wild leap of fantasy to propose that there is a promoter to insert it as well.

Viral spike proteins are a recurring motif. Not only human coronaviruses, but Respiratory Syncytial Virus, HIV, and influenza A all employ cleavage and fusion, suggesting an ancient ancestry in the same manner that our arms and legs still resemble those of frogs in form and function. The (theoretical) convergent evolution of a genetic promoter for removal and insertion of cleavage sites at the proper location would have trivially obvious fitness benefits seen from the perspective of the eons. No spike gene wants to be limited to its current “choice” about whether to cleave or not to cleave; there is always a long-term desire for flexibility. This same preference for flexibility is reflected in bacteria, where many of the genes responsible for pathogenicity are optional “plug-ins” in the form of plasmids or phages; insects and plants often play the same tricks. Toggling genes appear in nature because they keep other genes (which may contain the promoters that regulate toggling) alive when the fitness landscape changes.

Moreover, the precedent of “random,” g-heavy FCS auto-insertion in avian flu in multiple experiments dismantles the argument that the SARS-CoV-2 FCS insert is any kind of smoking gun for laboratory manipulation.

Therefore, there isn’t really a genetic argument that SARS-CoV-2 must be unnatural based on the FCS. However, and as stated above, the FCS insert can still be considered suspicious (in light of known pathogenic effects and human interest in the same).

If you derived value from this post, please drop a few coins in your fact-barista’s tip jar.

As reviewed in the linked post and originally hashed out in “Where’s Wuhan.”

Berry, DM. Cruickshank, JG. Chu, HP. Wells, RJ. (1964.) “The Structure of Infectious Bronchitis Virus.” Virology. 1964 Jul;23:403-7.

From p. 144. Jordan, Edwin O. (1927.) “Epidemic Influenza: A Survey.” Archived online at https://quod.lib.umich.edu/f/flu/8580flu.0016.858

— The comments on the 1891 illness are further quoted and discussed in “Should Variants Actually Happen, Pt. 2.”

More food for thought Brian! It is something worth considering when we argue that SARS-COV2 and other viruses would get weaker over time because otherwise they would kill off their hosts. I don't find this argument compelling, but if one were to follow this line of reasoning it would extend to other animal models as well. It's not like we can act as if we are so distinct from other animals.

I actually find a lot of fascination with steelmanning other hypotheses, otherwise we wouldn't be able to tell what arguments are out there. Irrespective of what position we fall into it's good to at least see other possibilities, otherwise we sort of gate ourselves into a narrow mode of thinking.

"Bats are not required to license their viruses with some federal agency; what we haven’t found today, we can at any point find tomorrow; and we have no very good idea how much of the genetic territory in question is still unexplored. No biological principle argues we should extrapolate from a lack of currently-known exceptions to suppose an impossibility of exception."

This was great with much needed clarity for many components. Lots of the science is way over my head but enough basics stick to put the key mystery puzzle pieces together. Your point here seems to apply to so much of the official positions that assume select experts know all that needs to be known & what they measure has all the information required for certainty.

Princess Cruise had enough people who never got sick the idea of some natural immunity seemed obvious & theory of also being completely novel seemed impossible. Given years observing the tracking abilities of our public health institutions any idea they could be ahead of the curve tracking anything makes novel virus story even more or a long shot.