The Qatar "Imprinting" / "Boosters Increase Reinfection!" Study

Prepare for an unsatisfying denouement on this one.

It’s imprinting! Ahh! We’re doomed!

A new study on post-Omicron reinfections hides a hilariously obvious-in-retrospect flaw.

The study:1

The claim:

Omicron reinfection rates were higher after the booster! Ahhh!

Well, not really.

A naturalistic summary of the findings would be, “Being double-injected before BA.2 infection added apparent protection against reinfection vs. being unvaccinated before BA.2 infection; but this same added protection is not found in the triple-injected-before-BA.2 infection group. They only do as well as the unvaccinated.”

Readers who just want to find out why this study is flawed should scroll to the bottom and read in reverse.

But like any puzzle, the solution is disappointing unless you work it out for yourself — readers who want to try to solve it before seeing the answer should therefore read this post from the top.

The set-up

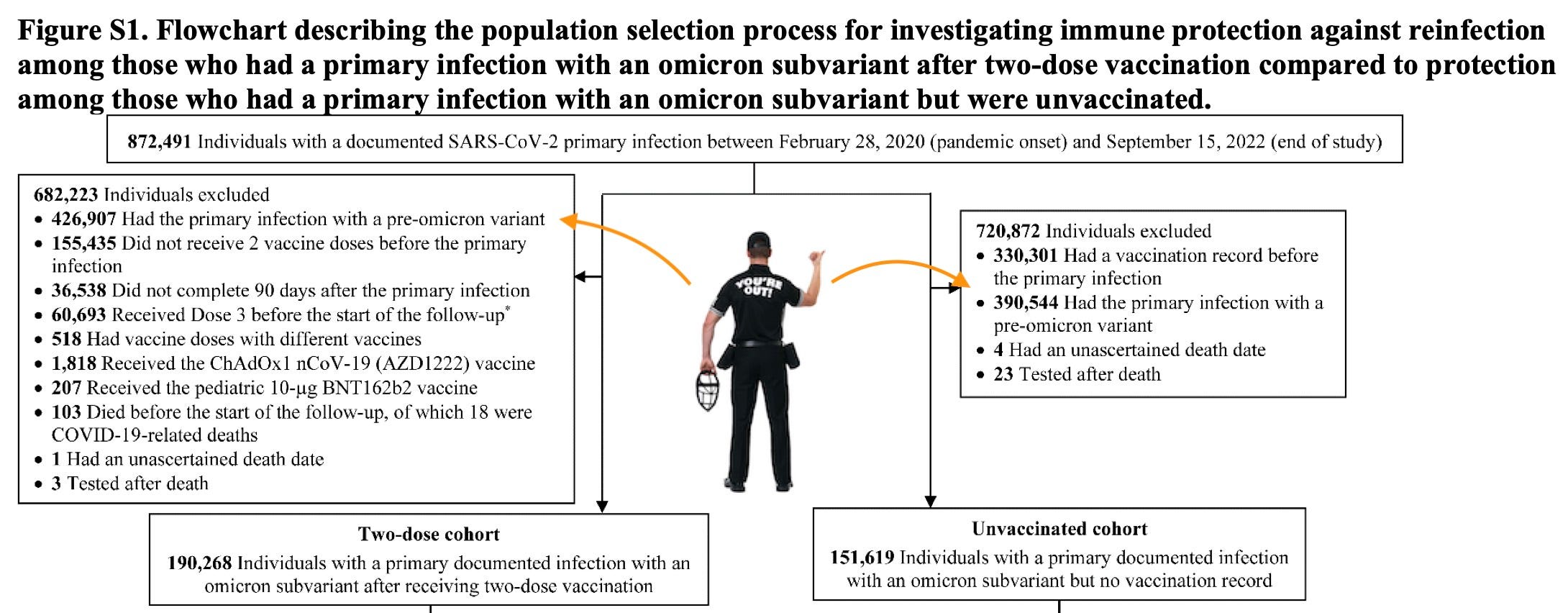

It’s not another junk “test-negative case-control” study, thank God. Instead, the authors construct three “matched, retrospective, cohort” sets in which individuals recorded as positive for the first time in the Omicron era are followed starting 90 days after their test, with comparisons between:

double-dosed vs. unvaccinated

double-dosed vs. triple-dosed

triple-dosed vs. unvaccinated

In all three sets, anyone with a recorded first positive before the “Omicron” era was thrown out.

And, naturally, no one with zero recorded positives is in the study either. And so from a bird’s-eye view of the population of Qatar, the observed groups in the study look like the following, in the first two sets:

The third set, Unvaccinated vs. 3rd Dose, is the same way. As it merely confirms that reinfection rates are similar for those two groups, we don’t need to examine it.

What is important is that the study takes out everyone with a confirmed previous infection before Omicron. So different rates of previous confirmed infection between groups does not matter — we can pretend that all those people were exported from the country. Likewise for anyone who has no infection record at all. Only the “Omicron primary infection” individuals in each category are compared.

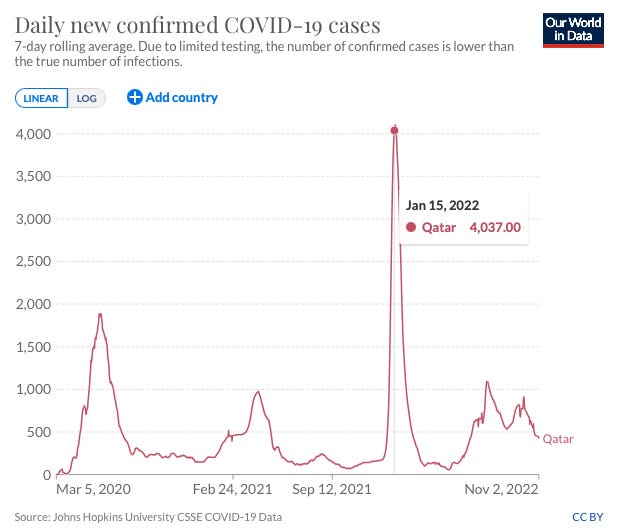

Since follow-up starts 90 days after the confirmed post-December 18 primary infection, technically the study will include primary infections all the way up to mid-June, hence the gradient and dashed line for the reinfection window. However, the case rates in Qatar make it unlikely that late-recruits were a substantial portion of any of our observed groups.

And the study text seems to confirm the same:

In double-dosed vs. unvaccinated

Double-dosed median primary Omicron infection: mid-January (based on my math-ing of the injection to follow-up median interval)

Unvaccinated median primary Omicron infection: mid-January (based on matching in study design)

In double-dosed vs. triple-dosed

Double-dosed median primary Omicron infection: mid-January (based on my math-ing of the injection to follow-up median interval)

Triple-dosed median primary Omicron infection: mid-January (based on my math-ing of the injection to follow-up median interval)

Ok, But Wait: This all looks crazy bias-introduce-y!

Indeed. Bias is an especially big problem in Qatar, where different demographics have different occupations and therefore different rates of exposure and testing; and also, of course, injection. But the study’s next design step is to match individual primary-Omicron-infected individuals to each other one-to-one. Anyone who can’t be matched 100% according to an extensive list of both demographic, and primary infection date, test type, and test reason values is left out of the reinfection observation group.

In the above cartoon example, only the three crayons who could find a “match” in terms of color, time and reason for testing (travel or medical), are going to be watched for reinfections. Nothing that happens to the un-matched crayons is being observed.

Cohorts were matched exactly one-to-one by sex, age, nationality, number of coexisting conditions, as well as SARS-CoV-2 testing method, reason for SARS-CoV-2 testing, and calendar week of the SARS-CoV-2 test of the primary Omicron infection.

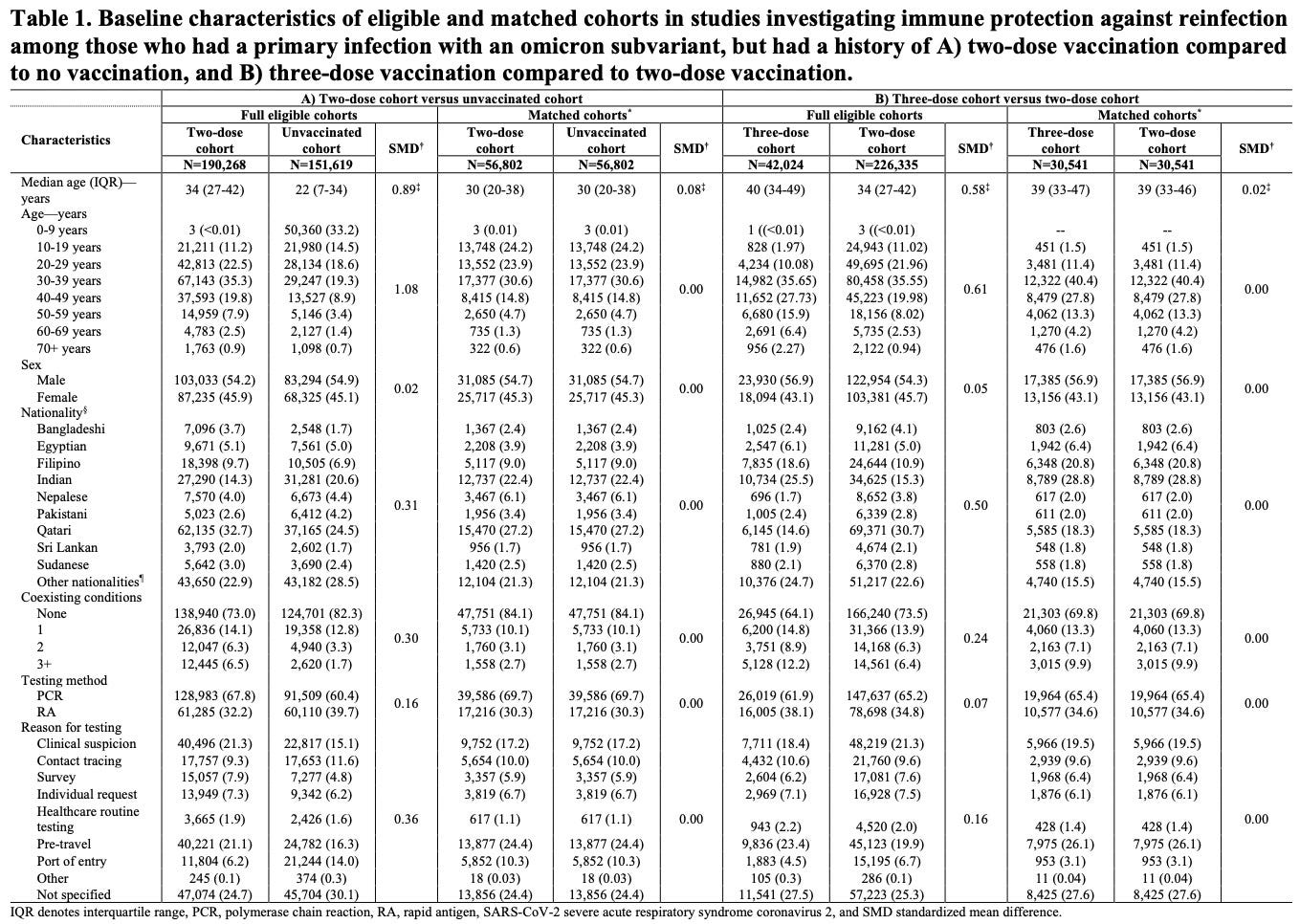

As can be seen, the result is that the matched group is identical in all values in both the 0 vs 2 and 2 vs 3 modules:

Theoretically, this should ensure that both the unvaccinated and double-vaccinated group are very similar in terms of future exposure risk and likelihood of testing. Even if there’s loads and loads of biases in the unmatched groups, the study is only looking at those individuals who were able to “match up” with each other on the week of their primary Omicron infection. For this reason, the demographics and later infection outcomes of the double vaccinated change when they are matched with the unvaccinated vs. when they are matched with the triple-vaccinated: Both acts of matching change who is being observed, and what type of exposure or testing risk they face going forward.

As a last note, matched individuals who are injected after their primary Omicron infection cease to have the same vaccine status as when follow-up begins. They are taken out of the “watched” group at this point, along with their match (whichever side of the aisle their match happened to be on). But any reinfections recorded between follow-up and injection are still in the record of watched events.

So, with such a bias-proofed design, what is the cause of the crazy finding of the triple-dosed having more reinfections than the double-dosed!?

The authors say “imprinting.”

They are hilariously wrong.

Findings 1: Double-dosed less likely to be reinfected than unvaccinated!

This actually isn’t surprising. Despite anecdotes of endless reinfections and “VAIDS,” lower chance of (already rare) reinfection has been observed in the double-injected in other studies which only compare results after the first infection, which are the source of the “hybrid immunity” trope used to justify injecting the naturally immune despite astronomically small absolute infection reductions.2 We can set aside whether the same finding in today's study still reflects some sort of bias smuggled in past the authors’ matching attempt. Really, all that is interesting about this finding is that it contextualizes the more “mysterious” finding about the boosted.

Findings 2: Triple-dosed more likely to be reinfected than double-dosed!

(Or, “Double-dosed less likely to be reinfected than triple-dosed or unvaccinated; triple-dosed and unvaccinated more or less equally likely to be reinfected.”)

As my caption mentions, follow-up time, reinfection risk (exposure and testing), reinfection rate, and even non-Covid-19 death rates (not shown) all change for any given cohort when it is matched with a different alternate one. To pick on the double-injected, matching them with the unvaccinated makes them more young and “essential worker”-y, matching them with the triple-injected makes them more middle-aged and professional:

The point of pointing this out is merely that the resulting fluctuations in raw outcome rates do not contribute to solving the mystery. They are part of how each of the three modules is carefully controlled to theoretically make the risk of reinfection similar between groups.

However, we can see from the effect of adjusting for testing frequency that there is still some difference in testing rates: The triple-injected seem to test more frequently than either the unvaccinated or the double-injected. As a result, our “mystery” has a range of apparent detrimental effect sizes for triple-injection: It either makes individuals 1.38 or ~twice as likely to be reinfected vs. the double-injected.

My reader may pause here, if you want to solve the mystery for yourself. I have tried to condense the examination of the study design to dispel what might be the most obvious questions or “leads.” I have not presented the final clue that leads to the answer, that is in the study text. Or, scroll below for the clue, and then the solution.

The Last Clue

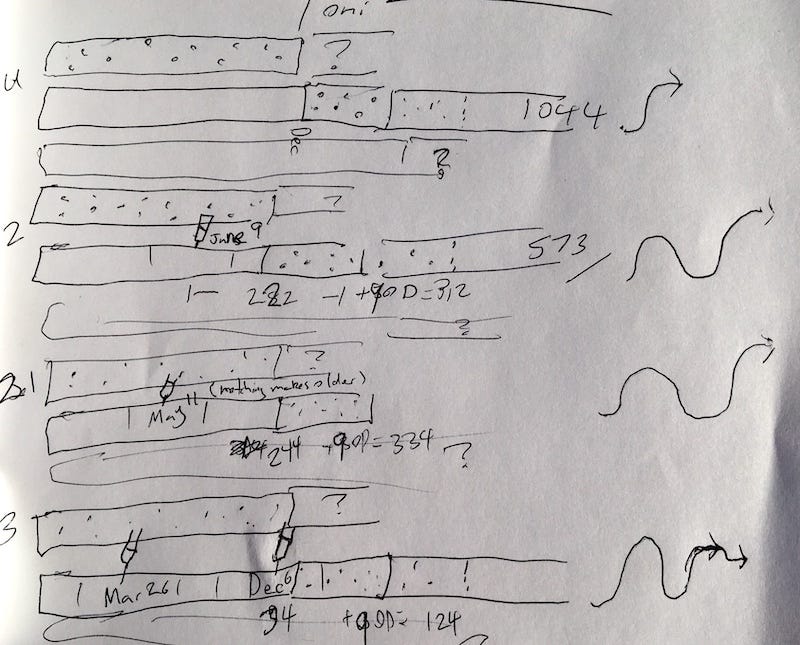

The solution to the mystery is buried in the text description of the methods section for the 2- vs. 3-dose module:

Figure S2 shows the study population selection process. Table 1 describes baseline characteristics of the full and matched cohorts. Matched cohorts each included 30,541 individuals. The study population is broadly representative of individuals with primary omicron infection who had received three-dose or two-dose vaccination in Qatar (Table S2).

Median dates of the second and third vaccine doses for the three-dose cohort were March 26, 2021 and December 6, 2021, respectively. Median date of the second vaccine dose for the two- dose cohort was May 11, 2021. Median duration between the third dose and start of follow-up was 124 days (IQR, 103-143 days), and between the second dose and start of follow-up was 334 days (IQR, 286-371 days). Median duration of follow-up was 157 days (IQR, 135-164 days) in the three-dose cohort and 157 days (IQR, 137-164 days) in the two-dose cohort (Figure 1B). There were 480 reinfections in the three-dose cohort and 248 reinfections in the two-dose cohort during follow-up (Figure S2). None progressed to severe, critical, or fatal COVID-19.

Solution:

“Primary Omicron” infections in the triple-dosed happened mere weeks after the third injection, when antibodies were super high. “Primary Omicron” infections in the double-dosed happened ~8 months after the second injection, when antibodies had been allowed to ebb. Remembering that individual “follow-up” starts 90 days after (post-December 19) positive test:

Median duration between the third dose and [primary Omicron test] was [34] days (IQR, [13-53] days), and between the second dose and [primary Omicron test] was [244] days (IQR, [196-281] days)

This extreme, “hidden” bias to just-after-injection infections in the 3-dose group plausibly drives higher reinfections by several means:

Masking of Omicron antigens by high pre-infection (anti-Wuhan) antibodies

Lower viral loads due to high pre-infection (anti-Wuhan) antibodies

Higher rate of false positives in January despite whatever longer-term similarities in exposure rates, testing rates, etc. pervade between the double- and triple-dosed. If recent injection lowers the rate of infection for a month, it also increases the rate of false positives (because of math, which is evil).

The last bullet is sufficient in itself: Because “reinfections” are a rare outcome, affecting a minority of each of our observed groups, any higher amount of false-positives in the primary Omicron infections for the three-dosed vs. the two-dosed will greatly skew the amount of later “reinfections” even if false-positives are still a minority of the three-dosed.

At the same time, there is nothing really wanting in the first two bullets. My on-paper solution to the problem includes a model where juiced-up, short-term antibodies diminish the Omicron-specific response that would otherwise have “boosted” overall Omicron immunity (as with the double-dosed, who go on to outperform the unvaccinated):

Conclusion: Rather than add support for “Imprinting,” this paper (if anything) refutes it.

Because the double-injected have more robust protection against later reinfection, even outperforming the unvaccinated, this paper supports the reasonable assumption that once antibodies wane, encounter with a variant virus results in a moderated, but still substantial enough level of antigen exposure to prompt a variant tailored response — whereas if the variant is met while antibodies are still high, the variant tailored response is muted. (This is the same effect observed when comparing Alpha vs. Delta post-injection infections, which likewise would have differed in “amount of juiced-up antibodies” at time of infection.3)

On the other hand, I leave an “if anything” modifier as it could simply be a greater amount of false positives that drive the different results observed for the double- and triple-injected.

And, of course, none of this will help anything that has to do with tolerance and sudden death.

Related:

If you derived value from this post, please drop a few coins in your fact-barista’s tip jar.

Chemaitelly, H. et al. “COVID-19 primary series and booster vaccination and immune imprinting.” medrxiv.org

See “Even Steven.”

A possible fourth bullet point:

If the triple-shot group was infected on average one month after their third shot, this creates a cohort of people *for whom the booster failed to prevent Omicron infection at the peak of antibody levels.*

That could be due to individual-level variation in immune responses and antibody epitopes, but it would not be surprising if the folks who were able to be infected one month after injection are, on average, producing a less optimal immune response to spike protein and thereby more vulnerable to reinfection.

Nice breakdown of that study, thank you. Jeez, every single study needs to be gone through with a fine tooth comb to make sure it's valid.