Polio series table of contents:

(Let’s also call this “The Polio Toxin Theory, pt. 2.”)

My series on polio would not really be complete without a post devoted to this topic. At the same time, to avoid redundancy, some of the essential arguments will be presented as references to other parts of the series.

Defining “worked.” (It just means worked.)

The definition of “worked” used in this post (and anywhere else in this series) is simply: “Reduced the incidence of epidemic polio paralysis.”

With this definition, the question being considered becomes, “What caused the reduction of polio epidemics after 1954 — the polio vaccines, or something else?”

This is not a consideration of the question of whether, somehow, the reduction of polio epidemics after 1954 was not a satisfactory outcome (e.g. because of occasional cases of polio still occurring here and there, including due to the Sabin oral vaccine). Accordingly, there is no essential significance to any differences in “how” the Salk and Sabin vaccines worked — though these differences are discussed.

So long as both played a part in “reducing the incidence of epidemic polio paralysis,” then both “worked.”

The Argument:

The trend in 1954 was that polio cases and epidemics were increasing, both in the US and elsewhere.

In Salk-era polio epidemics, the vaccinated were having less polio.

That’s the entire case — it isn’t some big, elaborate work of brilliance (no such thing is needed).

Further discussions will then be given to:

Alternate explanations for the decline (reclassification, toxins, etc.) — neither necessary nor convincing. (Totally faulty, really.)

Supplemental: The decline should not have been expected (in US or globally) — and in fact was not expected.

i. The trend in 1954

This series (regarding polio overall and the “toxin” theory of polio) is simultaneously a critique of the polio chapter in Turtles All the Way Down.

Turtles claims the following (spacing and emphasis added), supplying the graph reproduced below to illustrate the point:

The Salk vaccine, we’re told, was the main reason polio disappeared from the Western world in the mid-20th century.

The great epidemics of the 1950s, the official story tells us, all but vanished in the second half of the century thanks to universal vaccination campaigns. But this description oversells any role the vaccine may have had in curbing the disease.

In fact, the data show that a major decline in polio morbidity in the 1950s occurred before the vaccine was put to use. The United States was the first country to introduce the Salk vaccine. Figure 10-1 (next page) shows that the peak year for polio morbidity was 1952 (with almost 60,000 cases), followed by a consistent [“consistent”] decline over the next few years. By 1955, when vaccination was launched, morbidity had already dropped to about half of its peak level (29,000 cases). Mortality data followed a similar pattern: a steady decline from the 1952 peak (over 3,000 deaths) to about a quarter of that number in 1955.1

Let’s start with the grammatical issue: The Salk vaccine went into use in 1955.

As such, the phrase “By 1955” does not describe pre-Salk (IPV) polio case rates unless referring to 1954’s values. But this isn’t what the authors mean: 1955’s case count (28,386) is explicitly given as the “By” 1955 value, in order to claim that cases were then already “half” of the 1952 peak. But there were still 10,090 extra cases in 1954 (35.5% higher vs. the next year). Turtles cannot claim that these 10,090 cases disappeared in 1955 “on their own” by, to begin with, counting the missing cases in the trend.

In 1955, the Salk vaccine was already in millions of arms well before polio season: Foundation2 forethought and funds had been devoted to the goal of Salk-vaccinating as many children as possible in advance of summer, in the event that the 1954 field trial review led to approval. Polio occurs in the summer; the 1954 trial involved injecting children before summer and seeing how they fared; no imagination was needed to realize that children in 1955 could only benefit from the (approved) vaccine if they too were injected before summer.

From Oshinsky’s Polio:

As a result, he took a huge gamble that summer, betting that the polio vaccine would do well enough in the field trials to be licensed by the government and win wide popular support. In private meetings with six drug companies, O’Connor offered them $9 million of National Foundation money to manufacture the Salk vaccine at their normal markup, so that stockpiles would be available in 1955 if all went according to plan.3

It is therefore no surprise that 5 million children were injected in a few weeks in May, 1955 before the Cutter shutdown; some number more would have been injected once vaccination resumed. As such, Turtles cannot use case rates from 1955 to argue anything about natural or exogenous reductions — it is a wantonly fraudulent argument.

Besides the grammatical issue, Turtles makes the curious choice of superimposing case rates and death rates in the same graph. This would seem to serve no purpose except to suggest with no justification that the reader should “ignore” the excess in cases in the two years before before 1955.

That’s right —

American polio cases were higher in 1954 than the year before, and than all but two prior years in American history.

It is utterly farcical — in fact, delusional — to claim that the Salk vaccine was introduced in the midst of a natural, “consistent” decline in polio.

American cases were increasing in 1954 (polio was not going anywhere)

(Note: Comments on whether a trend of increasing baseline cases should have been expected to continue, or not, have been added to the bottom of this post in part “iv”.)

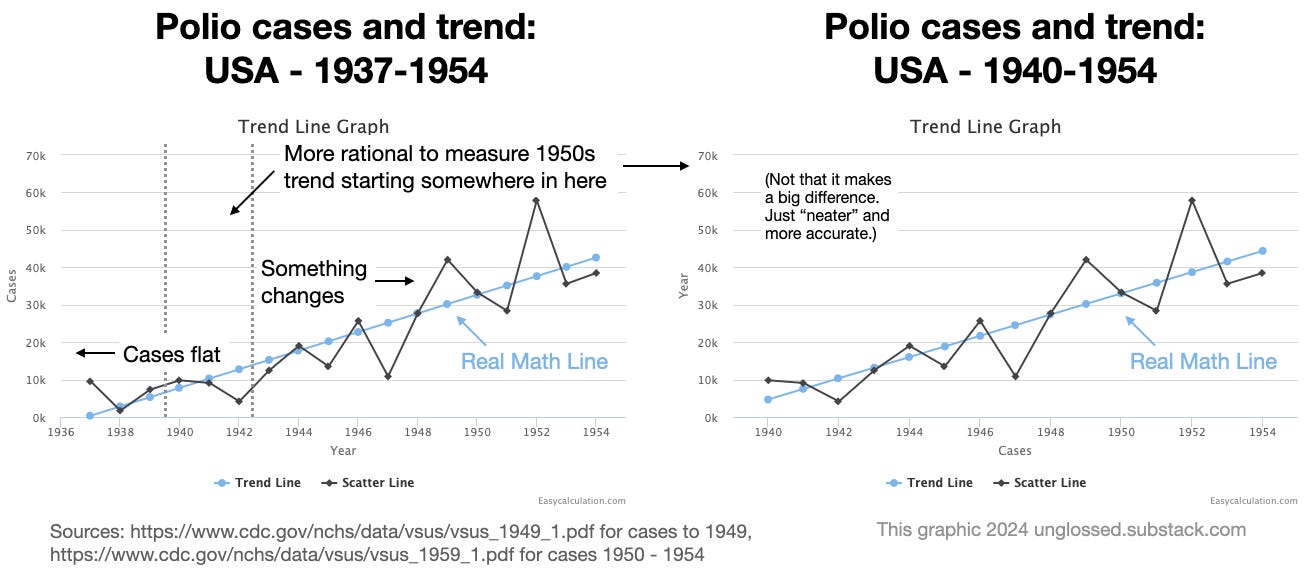

What does The Math say about American case rates in 1954? I asked it. For comparability with Turtles, the trend from 1937-1954 is shown on the left. Given the obvious bimodal nature of the trend before and after 1940, with stasis followed by increase, the first three years are removed on the right. It only makes a small difference to the trend, but reflects a more rational approach to actual case rates:

Turtles obviously counts on, and exploits, reader trust when smuggling 1955 case rates into the purported “trend” before the Salk vaccine. This is a lie: 1955 was a Salk year.

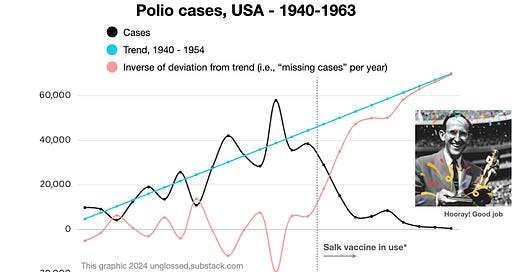

It also clearly stands as the beginning of a consistent, total deviation from the preceding trend. When the line produced above is extrapolated to the following eight years, there is little question that the previous yearly variability has been replaced by a new regime of more, more, and more reduced cases:

WOW! It says here (in the math) that the toxin theory is a heap of idiotic lies.

Further observations:

1955 itself (the first Salk year) is the largest negative deviation from trend (most missing cases) to have occurred since polio cases began to increase.

The increase in cases was accelerating between 1948-1954: There is more area above the trend than under it (in black; or under in red) in these years.

Besides a “baseline” increase in cases, cases tended to spike and wane in three-year cycles. It therefore should have been expected that 1955 would have been higher, not lower than 1952 — a new historic high.4

The deviation from trend in 1955 is not a one-off; it is repeated in the next two years, and never reverses afterward. Soon, all annual polio cases (expected by the trend from 1940-1954) are “missing.”

Essentially, Turtles wishes to berate the reader into hallucinating that the narrow and unremarkable deficit of American cases in 1953 and 1954 (with the latter year higher than the former) explains the extraordinary, sustained decrease that occurs afterward.

After all, if you pretend polio history began in 1952…!

This doesn’t make any sense — the deficit in 1953 and 1954 are merely part of the year-by-year deviation with the prevailing trend, and 1954 suggested an impending swing back toward higher cases.

Global cases were increasing in 1954 (polio was not going anywhere)

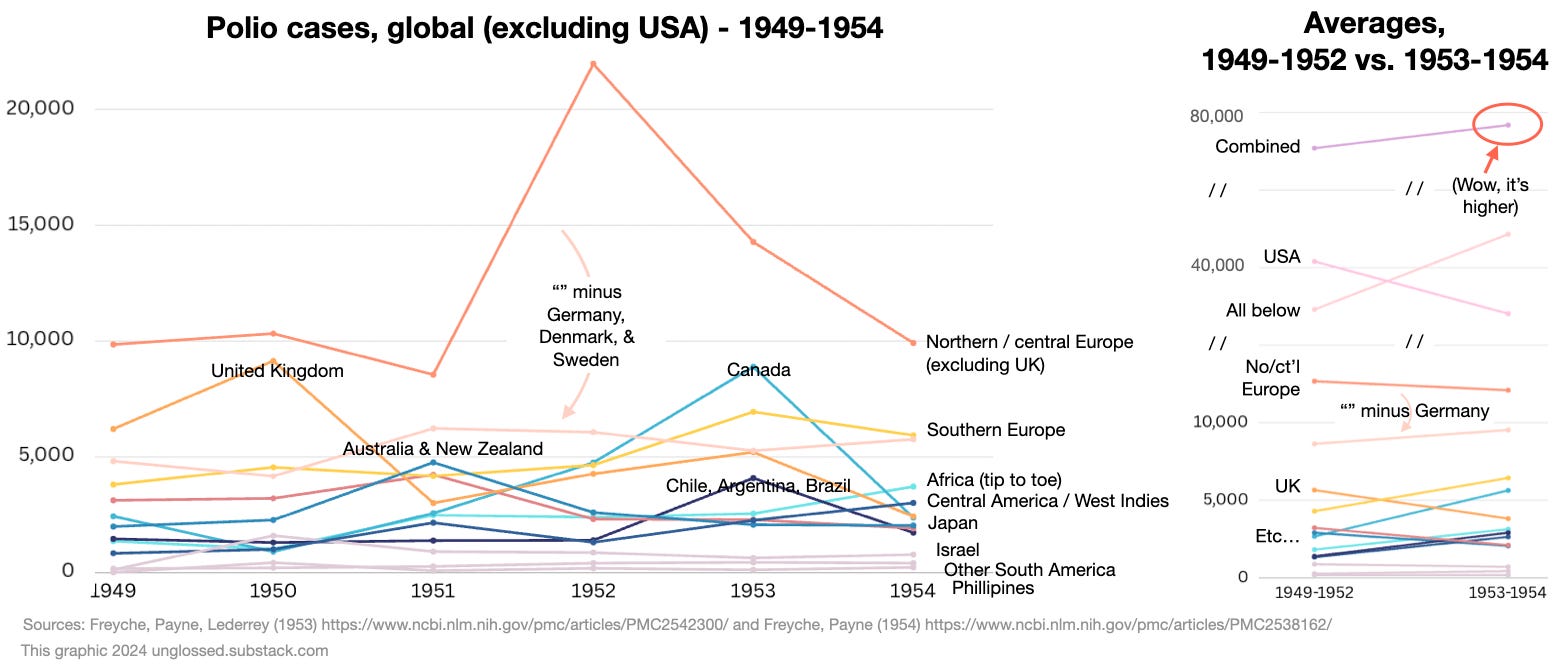

But even if, somehow, it did make sense to interpret the two-year-long American “trend” (of two entire years) in this fashion — is this sufficient to explain the eradication of a disease affecting the whole world? The USA was just one country; whereas polio epidemics originated in Europe, especially in Nordic countries. And so in these same two years of 1953 and 1954, what was going on in Europe and the rest of the world?

The answer is that polio wasn’t going anywhere.

Polio cases in most of the globe, compiled in this fashion, are in relative stasis. Cases in Africa are increasing — this is partly driven by novel epidemics (localized surges of cases) and partly (it might safely be presumed) by increased reporting of endemic cases. Northern and central Europe, the UK, and Canada experience more dramatic swings — but epidemic polio (with extreme regional variation) has been a volatile statistic in the global north for a half-century at this point.

It is therefore an unremarkable coincidence that northern and central Europe somewhat mirror the United States in recording a historic peak in 1952. In fact, this peak is almost entirely exclusive to Germany and Denmark; in other words, in the rest of Europe there “is” no 1952 peak (Sweden has a peak the next year).

Overall, even including 1952 into the average of cases in the years before 1953 to 1954 shows that the global trend in the latter two years was toward increase — strongly so outside of the US, and still weakly so even with the US thrown in (average case graph on the right of the prior image).

Conclusion: Some similarities, but more stability than US data

The European data mirrors the American data to an extent — it affirms that there is no reason to hallucinate some sort of “natural” decline in 1954. At the same time, it does not support the expectation of any broad increase in 1955, which is at contrast with the trend in the US. There is thus no reason (unlike in the US) to fret over the question of how quickly Salk-like or Sabin vaccines were implemented in Europe after 1954; most countries would have had one or the other in heavy use by ~1962.

Final notes on 1954 trends

In the US, as elsewhere, a notable quirk of the post-War polio epidemics was the increasing representation of adults. Here, I have taken the age distribution of hospitalized cases in Freyche, Payne (1954) to create a model of how case increases were spread among different ages after 1944:

Adults are not blind

The most important point is that in 1954, over 1/5 of hospitalized polio cases in the US were adults. It is distracting to comment here on precisely how this fact creates problems for non-viral theories for polio, but meanwhile is perfectly consistent with the viral theory. The reader may wield their own intellect on the question.

At the bare minimum, it is implausible that adults continued to experience epidemics of paralysis after 1954, without “noticing” due to some feat of statistical wizardry. Yet this, actually, is what Turtles claims took place.

It may also be noted that younger adults (up to age 40) were rapidly included in Salk vaccine recommendations due to contemporary recognition of these same trends. This is why younger adult white females are included in my analysis showing that the “reclassification” theory is implausible:

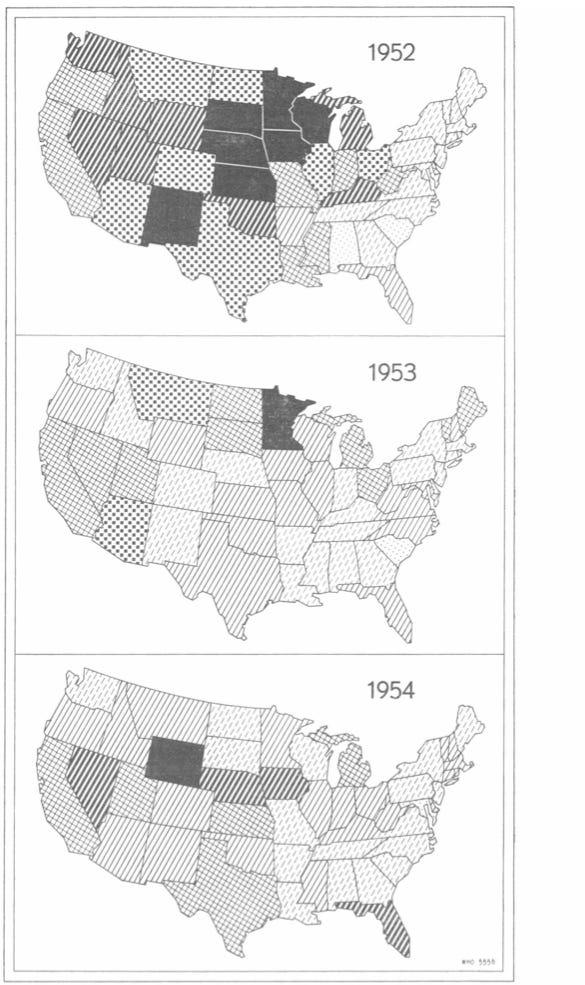

At the same time, it may be noted that American “declines” after 1952 were of course particular to whichever states had experienced surges in the same year. For most of the US, 1953 and 1954 were years of equal or increased cases:

This is noted merely to offer a complete picture of polio in America before the Salk era. It isn’t otherwise necessary to make this point — overall cases in 1954 were, again, the third highest on record.

ii. Who got polio after Salk?

When the Salk vaccine was used, polio epidemics were diminished.

Epidemics still occurred in the US up to the transition to the Sabin vaccine; but continental European nations which adopted their own IPV and maintained the use of the same achieved a temporary elimination of epidemics.

The Salk-era American epidemics, however, demonstrated the imperfection of the Salk vaccine; some vaccinated children were included in cases.

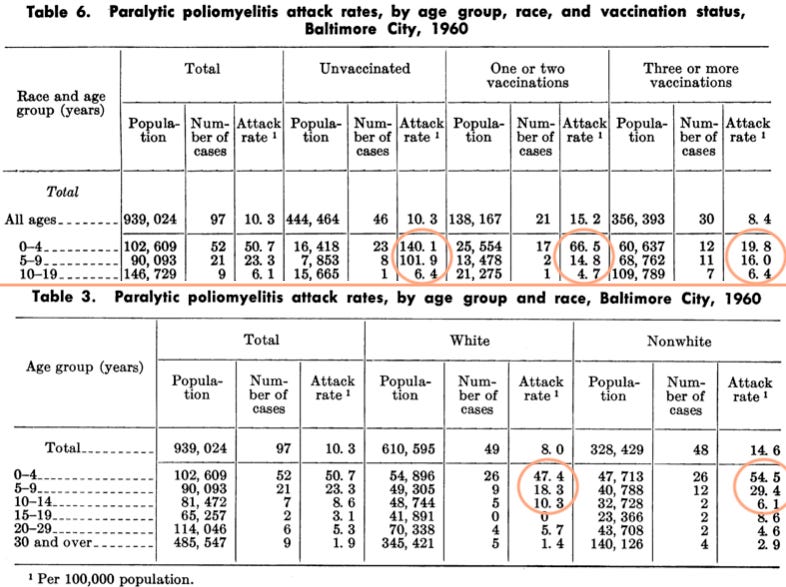

But they also demonstrated clear real-world evidence that the vaccine reduced case rates. In the three major urban epidemics of Chicago, Detroit, and Baltimore, the triple-dosed experienced polio at the lowest rates and with the lowest proportion of truly paralytic cases; the “partially” vaccinated were in between the triple-dosed and the unvaccinated. Black children were highly overrepresented among cases due to low rates of vaccination.

In Chicago, 1956:

In Detroit, 1958:

In Baltimore, 1960:

More Salk-era cases among the unvaccinated — What could be causing this? (it was the vaccine working)

If in multiple Salk-era epidemics, it is primarily those children who didn’t receive 3 doses who are showing up as paralytic cases, one must explain what “mysterious force” is preventing cases among children who received 3 doses.

There is no serious case to be made that some coincidental factor other than the Salk vaccine itself was this protective force.

Nor is there any serious case to be made that this is some statistical illusion; for example that the “unvaccinated” are actually vaccinated. The reason for this is simple; if in fact this were true, implying that the Salk vaccine conferred “protection” by inflicting polio on first-time recipients, it would defy explanation why there were no urban Salk era epidemics at any point in which white children were more heavily represented (let alone why such epidemics wouldn’t have been widespread).

iii. Reclassification and “toxins” are neither necessary nor plausible

Given the strong divergence from trend which prevailed after 1954, the Salk vaccine is sufficient to explain the decline in polio cases and epidemics — no alternate cause is required.

At the same time, it may be noted that neither reclassification nor toxins can plausibly explain this trend.

The problem with reclassification is that polio cases and deaths, if they are merely being reclassified, ought to still exist somewhere in the record. They do not (see the stand-alone post on this topic).

The problems with the toxin theory are myriad. Part 1 of this series has already discussed why the toxin theory is unsatisfactory in explaining the symptoms, seasonality, and epidemiology of polio epidemics.

But what about explaining the disappearance of polio?

Well, in this, the toxin theory — as advanced by Turtles or otherwise — is especially, in fact spectacularly, deficient.

DDT, for example, did not stop being used in 1955. And even if it had stopped being used — which it did not — such a pivot would not have immediately terminated human exposure to the chemical.

In particular, urban and suburban campaigns to combat Dutch elm disease and other insect borne threats to American tree populations were ramped up starting in 1955, and continued until the end of the 1960s. In these campaigns, DDT was blown throughout residential streets from mobile spray-canons, or dumped from helicopters and planes — in online anecdotes, children from the era report lounging underneath the trees afterward as they were still dripping with insecticide.5 These campaigns, which would in the end merely postpone, not reverse the holocaust of suburban elm, were directly responsible for the backlash against DDT, due to their obvious harm to American robins and other birds.

Yet Turtles concocts a queer, niche alternate-history of DDT use (and disuse), one which is devoid of any quantified values, and instead obsesses over the timing of certain documented kvetches by obscure doctors (the authors of Turtles would seem to be projecting).

This is bizarre, historical fiction. No one knows these guys. They don’t matter. They are nobodies who didn’t change anything, and even mentioning them is a waste of reader time — like the entire Turtles polio chapter.

Environmentalism, in American policy and media/commercial culture, does develop in response to a perceived crisis of DDT contamination and exposure — but this development does not take place until the 1960s, well after the eradication of polio epidemics. The prophet of the American environmental awakening was Rachel Carson, and her tome against pesticides — Silent Spring — was not published until late 1962. From wikipedia:

The impetus for Silent Spring was a letter written in January 1958 by Carson's friend, Olga Owens Huckins, to The Boston Herald, describing the death of birds around her property in Duxbury, Massachusetts, resulting from the aerial spraying of DDT to kill mosquitoes, a copy of which Huckins sent to Carson. Carson later wrote that this letter prompted her to study the environmental problems caused by chemical pesticides

Notice the problem here with timing? In (1955 and) 1958 (and later), DDT is still in use, even though polio is in extreme decline.

One often-encountered example is Detroit (where, as we have seen, there was a Salk-era polio epidemic in 1958). To quote from a 1960 report:6

The first known occurrence of Dutch elm disease in Michigan was found in Detroit in the summer of 1950. […]

A number of communities started control programs in 1953 or 1954 and by 1959 at least 35 cities and townships within the three counties ringing the sprawling metropolis of Detroit had had control programs underway over a several-year period (Lovitt, letter).

Steps in the control program consisted of […] a spraying program with DDT to kill, control, or prevent the spread of the bark-beetle vectors of the disease. Most communities followed State and Federal recommendations7 (see Michigan State University Extension Folder, F-195, and U.S. Department of Agriculture Belletin No. 193) in the matter of formulations, dosages and methods of application […] In the earlier years of the programs both foliar and dormant sprays were used, with two or sometimes three applications annually, but the tendency in recent years has been to reduce the applications to one dormant treatment per year, either in the fall after leaf drop or in the early spring before the elm buds open. Hydraulic sprayers were used mainly at first, but there was a gradual conversion to mist blowers over the years […]

With the adoption of the full-scale spraying programs in 1953 and the years immediately following, residents in the heavily sprayed areas began to report considerable numbers of dead and dying birds, particularly robins, with the symptoms commonly associated with nerve poisons.

In the matter of timing, the elm spraying program produces three problems: Spraying is implied to expand to more communities after 1954, when polio is declining; spraying takes place at first multiple times per year, whereas polio never undergoes multiple waves or peaks in a given year; spraying later takes place too early and too late for polio. In sum, DDT spraying in residential areas did not correspond to polio timing.

The example of Sheboygan, Wisconsin is similar, and gives an idea of the duration of spraying after 1960:

Regrettably, Dutch elm disease found its way to Wisconsin in 1956, and to Sheboygan just four years later. […]

Naively, Dutch elm disease was not considered a serious threat, even as an aggressive program of spraying began in 1957. DDT was the pesticide of choice, recommended by the State of Wisconsin Agriculture Department and the DNR. Sprayed by plane and truck in Sheboygan, the city of Sheboygan Falls used helicopters. Spraying slowed the progression of the disease but certainly did not stop it.

City officials knew they were losing the Dutch elm disease battle by 1968. Trees were dying at a rate of 1,000 per year in the city. In a September 1966 editorial, the slogan “City of Elms” was quietly retired. In early 1969, Wisconsin declared DDT to be a hazardous pollutant and recommended strongly that the pesticide not be used in the state. It was banned in 1972 because, as we know now, DDT didn’t kill just the beetles.8

Meanwhile, here are yearly polio case counts for Michigan, Wisconsin, and nearby Illinois (where spraying also took place) in the 1950s:

(One might almost conclude that DDT exposure protects against polio epidemics — of course, this theory was a common trope in the early 1950s, but is not consistent with examples from southern states where DDT was used to control malaria before 1950, with no obvious effect on polio case rates.)

By 1962, and the publication of Silent Spring, polio cases and epidemics were already “not a thing.” Yet DDT was still used at the time and in the years afterward, in crowded residential environments.

Further, even if DDT use had been halted in 1962 (not that such a halt would retroactively explain the reduction in 1955), all previously deployed DDT would have been as potent and plentiful as before. DDT lingers.

An article appearing in American Heritage in 1971 summarizes the state of DDT in the 1960s:

Predictable in a general way by the pattern of events was the sad case of the Bermuda petrel, a carnivorous bird that feeds solely on oceanic life far from any area where DDT is used. The bird comes to Bermuda for only a few hours, at night, to lay its eggs. It eats nothing there. Yet its eggs in the late 1960’s contained 6.44 p.p.m. of DDT on the average, and its reproduction was declining at a rate which, if continued, must end in complete reproductive failure by 1978. Even Antarctica’s Adélie penguins, Weddell seals, and skua gulls, carnivores all, were soon found to carry trace amounts of DDT in their fat, though they live thousands of miles from the nearest area of DDT use. Undoubtedly they ingest DDT residues in their food.

But DDT was also found, in the 1960’s, in Antarctic snow,∗ indicating that the food chain is not the only means by which the poison spreads. Studies conducted in Maine and New Brunswick, Canada, in the 1950's showed that approximately half the DDT sprayed over forests at treetop level hung suspended in the atmosphere to be spread worldwide on the wind. DDT attached to erosion debris also travels in irrigation water, rivers, and ocean currents. […]

In 1963, in direct response to the public concern aroused by Silent Spring, President Kennedy’s Science Advisory Committee recommended a reduction of DDT use with a view to its total elimination as quickly as possible, along with other “hard” pesticides. Soon thereafter Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall issued an order banning the use of DDT on Interior-controlled lands “when other chemicals can do the job.” Wisconsin, Michigan, California, Massachusetts, and other states began to move toward state prohibitions of DDT. Finally, in November of 1969, acting on the recommendation of a special study commission on pesticides, Robert H. Finch, Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare, announced that the federal government would “phase out” all but “essential uses” of DDT within two years. Many Americans assumed that this phasing out means the end of DDT. But not so.9

The appropriation of Carson’s impact in Turtles can once again only be described as bizarre (almost insane).

Not only does Turtles invent an alternate history in which, somehow, secret reductions in DDT take place almost a decade before Silent Spring, due to an obscure crusade by forgotten nobodies — leaving unexplained why there was still so much industry resistance to the bestseller in 1962 — but also, reason itself is suspended in appraising the likely relevance of DDT to human health.

The chemical remained and remains abundant in the environment in the developed world despite the reduction in use (in the developed world) after 1962. So what? There is still no more polio. Furthermore, the 1940s malaria eradication campaigns offer multiple case studies for investigating any link between DDT and polio. They don’t exist. Overall, it would seem that the negative reputation of DDT which was cemented after Silent Spring was a bit overblown; and certainly it doesn’t seem harmful enough to provide a plausible candidate for polio — otherwise, polio never would have stopped in the US, due to the lingering presence of DDT.

So what is Turtles even talking about?

iv. Supplemental: The decline should not have been expected (in US or globally) — and in fact was not expected.

Just a Curve™?

I received pushback in the comments based on the impish notion that the American polio case trend of the early 1950s was merely the left-hand side of an Epidemiologic Curve™.

This is not an appropriate or valid way to interpret year-on-year case rates. “Epidemiologic Curves™” operate on the scale of days and weeks — including for polio (literally, see the curves in the urban Salk-era epidemics above). And yet:

They are not an iron mathematical law which must (absent mechanical justification) apply to anything labelled an “infectious disease” at all times.

They have no great relevance for yearly rates, especially when tracking polio over a large area (polio was extremely heterogeneous in geographic distribution).

Regarding (1), “Curves™” are habitually irrelevant when it comes to most infectious diseases in the tropics. For example, even a so-called “epidemic” of Dengue Fever will tend to present without a bell-curve distribution.

The acolyte of “math rules epidemiology” might counter that, well, tropical, insect-borne viral illnesses are subject to special rules: Very well, such a cop-out merely verifies the more important point: Mere “epidemiologic-ness” and mere “infectiousness” are not the limit of considerations in how infectious disease cases should be distributed over time. Other stuff counts. “Other stuff” could be insects, or it could be human interventions… like the polio vaccine.

For polio specifically

The tendency before 1947 was for particular regions to go several years between relatively large epidemics. The tendency afterward was for regions to experience epidemics multiple summers in a row. Polio transitioned from highly sporadic to semi-sporadic. This transition was the engine driving an increasing baseline underneath yearly variability (light and heavy years relative to the increasing baseline).

This was simply an observational reality. No one observing it in 1951-54 could have, or did, predict that “Relentless Polio” must simply cease to be observed in precisely 1955, or any other year, because Look This Math Law. Relentless Polio — constantly increasing cases — was simply the “new normal.”

One thing to note about the constant increase in American cases in the early 1950s is, as noted in part i, a substantial heterogeneity. Because in the 1952 surge for example the East Coast was rather uninvolved, nothing about the selfsame surge could have prohibited new, record-high epidemics in the ensuing years — given that the East Coast had traditionally been the flag-bearer for polio epidemics in the US. (No such epidemics happened; but here the Salk vaccine plausibly can claim credit for preventing the falling of the shoe in question.)

This same heterogeneity was the one-and-only “rule” that could be applied to polio — and it meant that wherever cases were collated nation-wide, there were no “rules” dictating that yearly increases must reverse. There was plenty of unspent fuel in 1954, everywhere.

(How much spent fuel? This could be litigated by sero-surveys, which give an idea of how many people have accumulated natural immunity; except that few took place in 1955, and reliable comparison to historic antibody rates before 1950 are not possible.)

Anyway, it remains that in certain select regions, in the early 1950’s, polio cases did increase year on year. As polio don William Hammon wrote in late 1952 (emphasis added):

The great severity of the disease in the Sioux City [Iowa] area [in 1952], as judged by the high proportion of bulbar cases, the extent of paralytic involvement, the high case fatality rate, and the phenomenal morbidity rate (greater than 400 per 100,000) in the wake of six consecutive previous epidemic years (see this issue, page 750) testifies to the great invasiveness or virulence of the strain or strains active in this areas10

In other words, polio researchers in the early 1950s were quite resigned to the fact that polio was increasing in general. They did not bluster and protest about any iron laws that, any day now, would spontaneously return annual polio case rates to zero.

But, why not?

Because no such iron laws exist.

Yearly trends in infectious diseases are not defined by iron mathematical laws. They are a complicated product of billions of discrete interactions between the pathogen, host, environment (climate, bystander organisms, etc.), and reporting trends.

As such, literally nothing can prohibit the ceaseless increase of any particular infectious disease, beyond such mundane, pragmatic principles as “there is a limit to everything,” and “nothing lasts forever.”

Should polio’s increase have reversed in 1954?

Or have gone on for another decade? What does comparison with other diseases say? Here are four others:

Two of these diseases undergo increases which reverse more quickly than polio — but due to specific interventions (DDT for typhus fever, and a broad campaign of dairy policies for brucellosis). Two others simply plow forward, increasing without end — no control efforts are available.

So to which category does polio belong? Given that, like typhus fever, the reversal in increasing cases took place exactly when a specific preventative was placed into use?

This question isn’t even serious.

Even supposing that “iron laws” demanded the reversal of the American polio increase of the 1950s, the coincidental timing is too much to swallow. Why didn’t the reversal happen in 1948, or 1950, or 1953? Just what was it that made the reversal “wait” for the Salk vaccine? (Answer: The fact that the Salk vaccine was needed to effect the reversal.)

The ceiling on increase

Theoretically, the ceiling on infectious disease incidence is the population itself (or however many are added to the population per year, when measuring yearly).

The above graph represents all respective disease notifications, firstly, as a percentage of their average in 1935-1944. Although polio climbs the highest in this way of looking at things (i.e. in percentage), it never comes close to the absolute increase in yearly cases for “scarlet fever / strep throat” (shown in the second graph). For some raw numbers:

The all-powerful importance of “other things” in yearly trends (and which “other thing” caused the polio increase)

Hence the absolute absurdity of suggesting that diseases should follow “Epidemic Curves™” in yearly trends. These same trends are only partly a manifestation of the same dynamics which drive the time-distribution of cases during discrete outbreaks (i.e., increased cases lead to depletion of susceptible people to have cases). Many diseases are in equilibrium — a similar number of new susceptible people are infected and “depleted” every year — but not all. Disequilibrium does not demand a return to any particular mean, because it may be driven not by the dynamics of discrete outbreaks, but by “other stuff.”

“Other stuff” includes increased population (due to migration or high birth rates in a given area) or vice-versa; increased reporting or vice-versa; increased host susceptibility or vice-versa; and increased virulence of the pathogen responsible for the disease. Only the last of these is not subject to human social influences; as such, yearly disease trends tend to be like yearly statistics for any other social measurement (such as crime, etc.). The screen-grab above depicts the very first years in which infectious hepatitis was a reportable disease; the dramatic increase in cases mostly reflects subsequent changes in medical awareness and reporting.

Back to polio

The point, with polio, is that there is no prima facie justification for supposing that the trend of increasing cases should have reversed naturally.

In fact quite the opposite: Polio’s increase was driven by all three of the non-pathogenic “other things” listed above — more people, more reporting, and higher rates of susceptibility11 — and potentially by pathogenic factors as well (increased prevalence of virulent strains in the 1950s).

To suppose that all three (or four), let alone any one of these things coincidentally ceased to be a factor in 1955 exactly is an extraordinary claim requiring extraordinary proof. Which is to say, the Salk vaccine does not need to be defended against such fantastic imaginary scenarios — when it was used (in the US and elsewhere), polio was reduced. One does not suppose that when a door is closed, and the draft goes away, it’s just a silly coincidence, or a natural restoration driven by sacred mathematical laws.

(Only the “reclassification theory” deserves a special mention, because it supposes an intentional coincidence of timing — but, again, the evidence disproves the theory.)

If you derived value from this post, please drop a few coins in your fact-barista’s tip jar.

Anonymous. Turtles All The Way Down: Vaccine Science and Myth (p. 449). The Turtles Team. Kindle Edition.

As in, the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis / March of Dimes, which had funded polio research and the Salk trials, etc.

David Oshinksy. Polio (p. 200). Oxford University Press. Kindle Edition.

Alternately, it’s plausible that 1952 was the end of an adjustment period finally collecting all the immunity debt of the pre-War years. This relates to the comments in the “other trends” section.

https://www.atdetroit.net/forum/messages/148145/142686.html Accessed February 3, 2024:

It was great fun watching the spraying through the window. The sprayer guy operated something like an anti-aircraft set up. His seat would pivot around with the sprayer and he could pivot the sprayer up or down.

The spray had such velocity that it bent back branches. Maybe there was a fan built into the sprayer.

After the sprayer, we were allowed outside. The spray dripped off the elm trees upon us. It smelled ok. We played on the grass under the trees as if a storm had ended.

Wallace, GJ. Nickell, WP. Bernard, RF. (1961.) “Bird Mortality in the Dutch Elm Disease Program in Michigan.” Cranbrook Institute of Science - Bulletin 41. At http://shipseducation.net/pesticides/library/wallace1961.pdf

So, there was no top-secret walking-back of DDT recommendations on the Federal level in the 1950s? But what about Dr. Biskand?!?!

Beth Dippel. “Sheboygan is Tree City USA, but once was known as City of Elms.” Sheboygan Press. May 4, 2018.

Hammon, WM. et al. (1954.) “Evaluation of Red Cross gamma globulin as a prophylactic agent for poliomyelitis. 5. Reanalysis of results based on laboratory-confirmed cases.” J Am Med Assoc. 1954 Sep 4;156(1):21-7doi: 10.1001/jama.1954.02950010023009.

This is indisputable given that while overall cases were increasing during the Baby Boom, the representation of adults among yearly cases was increasing as well.

What I learned during this pandemic is that vaccines are very complicated. Each has amazing history, like a detective story. Some work and some do not. All have shortcomings of various importance. Some are outright scams but some are NOT outright scams.

Great article as always!

A couple of papers seem to suggest that polio myelitus epidemics increased because improvements to sanitation meant that infections were happening later in older children when there was less protection from maternal antibodies and so disease severity was greater:

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/47555926_From_Emergence_to_Eradication_The_Epidemiology_of_Poliomyelitis_Deconstructed

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/11450825_The_Polio_Model_Does_it_apply_to_polio

Secondly I wonder if diseases like malaria give some cross protective immunity to other diseases, so reducing malaria through DDT use would indirectly affect these other diseases, though this would only apply to some rural areas:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Malaria_US_curves.gif

It looks like malaria infection can give some cross reactive protection to SARS-Cov2, maybe that would help explain why Africa was not disasterously affected by Covid?:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-022-26709-7

BTW it looks like Pierry Kory also subscribes to the DDT hypothesis, so I guess great minds are not infallible:

https://pierrekorymedicalmusings.com/p/debate-was-covid-19-a-pandemic-caused

It seems like immunology is a vast universe poorly understood by mainstream science, and tinkering with vaccines, though strongly beneficial in some cases, is ignorant of more distant effects elsewhere...