The polio "reclassification" theory

Preposterous, lazy, and wrong.

Polio series table of contents:

[I]f poliomyelitis were removed from the list of reportable diseases in all States, an informal reporting system would develop overnight. Newspapers, teachers, various business enterprises, hospitals, nurses organizations, and other agencies would collect, pool, and exchange information on the occurrence of the disease, not because these agencies have control measures which they could institute, but because poliomyelitis is a disease of both local and national interest, and that interest will be satisfied with or without an orderly reporting system.

AD Langmuir, 19521

A fantastic amount of work has gone into the following presentation, but the result will be as brief as possible. Just to get to the point, the post is organized as follows:

Results: Polio and “alternate” deaths before and after vaccines

Introduction / Background

Focus on 1957-1959: Reclassification is not plausible

Methods: Polio and “alternate” deaths before and after vaccines

Raw data and notes

However, an introductory disclaimer:

This post is about facts, and accurate understanding. The reader is of course free to imagine anything he wishes about my opinions on vaccination based on whether or not I think the polio vaccines worked — but whatever the reader imagines will depend on an assumption that my believing “the polio vaccines worked” exerts absolute demands upon my opinions. In other words, the reader must assume that there are no other considerations to the whole question. This is a stupid assumption, and one that cannot lead to a truly considered skepticism of vaccines. “Vaccines work, and anyone dying of an infection ever is so horrible and awful, so everyone must use vaccines” — this is merely the precise mirror-image of the fanatical pro-vaccine mindset.

In fact (though I cannot stop anyone from imagining otherwise), it was not because I shared this mindset that I set out to show that vaccines besides polio appear irrelevant to childhood mortality. It is simply useful to actually know what effect vaccines have or haven’t had when discussing them, that is all.2

Results: Polio deaths truly declined after 1954 (no magic reclassification)

The crux of the question addressed by this post is — did polio deaths really decline after the polio vaccines, or were they just reclassified, throughout the entire United States almost overnight, thanks to some increased verification standard imposed from on-high?

The methods section, further below, gives context for how the answer was approached. To spare the reader from scrolling, however, here are the results:

Since the reclassification theory posits that polio case reductions resulted from lab verification requirements, the question naturally arises — what would happen to these hypothetical “disqualified,” “reclassified” polio cases?

In the case of deaths, some cause still must be reported to the Public Health Service. We should therefore expect that polio deaths were instead submitted as a number of eligible syndromes related to infectious or spontaneous neurological inflammation and paralysis. As such, the classifications “other infectious,” “non-meningococcal meningitis,” and “cerebral spastic infantile paralysis” are most likely. “Acute encephalitis” and “nervous system — other” are included to round out the picture.

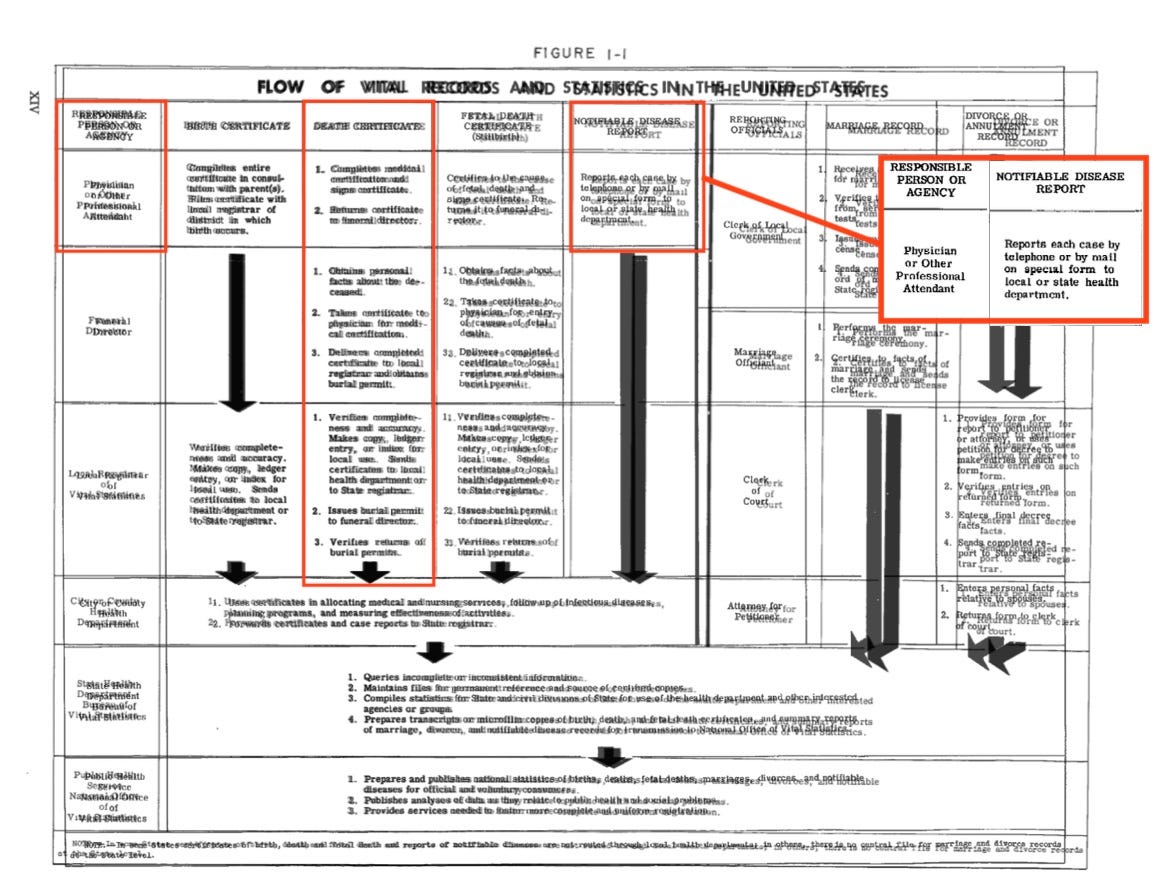

Anything beyond these causes might be looked at — but reclassification into categories beyond those already selected wouldn’t coherently follow the reclassification theory. The conceit of the theory is that someone in the death reporting process (either physicians, funeral directors, local registrars, or local or state health departments) is reclassifying what was previously considered a polio death because of a lack of lab verification or negative lab verification: Naturally, this individual will still want to describe the death with relevant terms. The reclassification theory does not posit that every doctor in the United States (and all around the West) simultaneously received a letter with a 5 dollar bill and a request to call polio deaths “appendicitis.”

And so we may examine raw deaths for relevant pre-vaccine and post-vaccine years. These deaths may be expressed as rates relative to any number of denominators. In the case of polio and the “alternate” causes, I have chosen to show them as a percentage of all deaths not classified to certain other major causes.

The center graph models what should be expected in 1957-1959 if polio deaths are simply being reclassified due to sinister lab verification requirements. The right-hand graph, however, reveals the actual rates.

Because the sum of polio and the “alternates” is substantially lower than the pre-vaccine years, it can be concluded that polio deaths were reduced and not reclassified. This conclusion is most robust in the age bands where polio is nearly equal to all of our “alternate” causes in the pre-vaccine years, i.e. everything from 5-9 to 35-39.

Older children and younger adults

Let us focus on the before and after among these two age groups. After initial posting, this segment has been rebuilt using more rational age-groupings based on the observed mortality trends. These age-groupings were determined using sophisticated mathematical analysis methods.

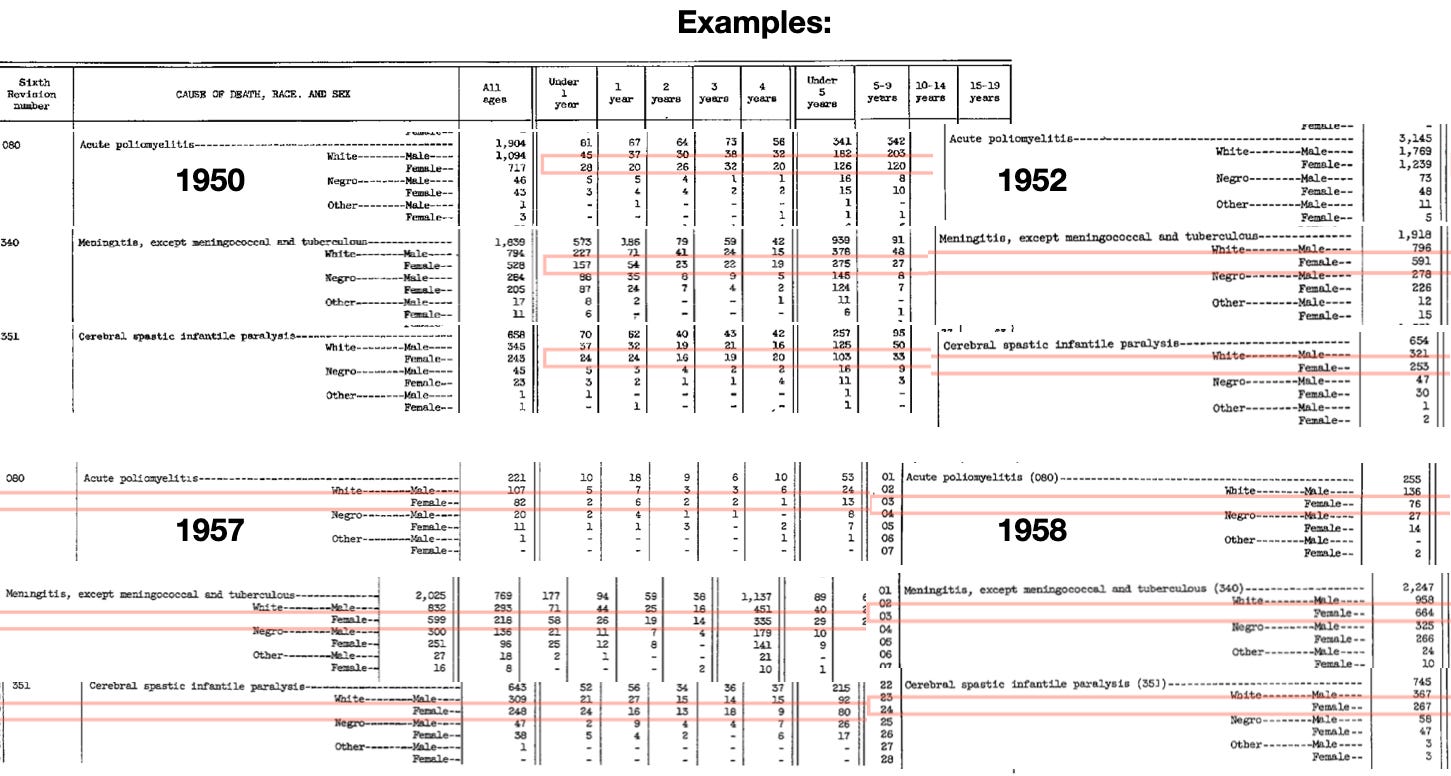

5-14 year-olds experience similar polio and “alternate mortality trends,” as do 15-29 year-olds — when measured against all mortality minus certain major causes. Just for a sample of what these percentages look like in raw numbers (before the influence of different mortalities for other causes in the denominators):

Polio is second-most deadly in 5 to 9 year olds in 1950, but almost as deadly in 25-29 year-olds. These numbers are not proportional to case rates; there are fewer cases in adults, but cases are more frequently lethal. How then is it that older teens and older 20 year-olds may be grouped together? The “unifying force” is in the background rate of overall deaths: The latter group is dying more “generally;” teens have the lowest death-rates “generally.” The point is that our groupings are, in fact, only rational under the conceit that “polio” is not a distinct entity, but just a statistical figment that is being reclassified after 1955. In “real life,” it isn’t so rational to lump older teens and 20 year-olds together; in our imaginary “reclassification” verification attempt, it is permissible.

On with the focus on how these percentages look after the vaccine:

Because polio must be included in the denominator, any true decline in polio mortality will result in the percentage of alternate causes increasing — because there are now fewer overall deaths. The annotation in the upper right shows the “expected” end-point values for the alternate causes based on this overall reduction. There is very little difference between the expected and observed rates — at most, it would seem, a tiny handful of former polio deaths are still occurring but being “reclassified.” (The original version of this post, because it used pre-selected age groupings with more heterogeneous mortality, did not show such a consistent mirroring between the expected and observed post-vaccine portion of “alternate” causes. The difference was still trivial.)

While synthesizing this great mass of statistics is practically difficult, it only results in a conclusion that already appears at a glance at any individual set of figures. The following provides a second example of the raw numbers which feed the graphs above:

All-ages values for polio deaths among white females are 1,956 in the two example pre-vaccine years combined, and 158 in the two example post-vaccine years — a difference of 1,798. Despite this, the other two sampled causes have decreased by 10.1% as well3 — the missing polio deaths have not been reclassified. In fact, the reduction of true polio would naturally have reduced un-diagnosed and mis-diagnosed polio.

Background - The polio “reclassification” theory: Why haven’t proponents actually looked into it?

(This introduction is written as if preceding the results section.)

Last week’s post, regarding how no vaccines besides polio can take (knowable or plausible) credit for childhood mortality reductions before or after 1953, triggered readers devoted to either or both of two alternate theories for the emergence and disappearance of polio. These are the toxin theory and the “reclassification” theory.

I have already dealt with why the toxin theory is fatally implausible — and although the toxin theory depends entirely on reclassification, in order to account for why polio cases and deaths declined exactly when the vaccines were used, I do not want this post to be construed as a “further treatment of the toxin theory.” It doesn’t require this additional refutation; the previous post is sufficient and unanswerable.

So while some commenters, as said, were invested in both theories, this post is exclusively a look at reclassification. This theory clearly has legs of its own, with many commenters under the impression that it has been shown, somehow, by anyone, that such a thing as this actually happened:

As far as I'm aware, the CDC redefined Polio in order to fake vaccine efficacy*. This may be why it stands alone as a vaccine which actually seemed to work.

Brilliant really; they could have stopped Covid overnight just by changing the definition of infection to include the ability to fly.

The given link leads to an article which flogs the reader with a long course of quotations from the post-polio era, in which the problems of distinguishing polio from not-polio in the twilight and night of the polio era are discussed. These are reasonable considerations which stem from 1) Wanting to know if the vaccines were working (and not inaccurately conclude otherwise) and 2) The fact that the vaccines, actually, were working (though the Salk worked rather badly).

This is true of any quality that can be misinterpreted. As an example, sometimes apparent rude gestures turn out to be misunderstandings. If I have a button that prevents all rude gestures on Earth from ever occurring, then 100% of future apparent rude gestures will in fact be misunderstandings. This hypothetical problem doesn’t mean anything if you are in the East Coast — most apparent rude gestures are in fact rude gestures. All that is unique about infectious diseases — the only reason this problem comes up — is that they alternate between being frequent and rare. This doesn’t mean they are always rare; that their occasional rareness “proves” they are never frequent. There’s nothing one can say to someone who thinks otherwise except, “thanks for letting me know about your low IQ.”

But more to the point, what is all this quotation-doing proving? If polio cases and deaths were reduced from their early-50s record highs by “reclassification,” why isn’t anyone showing the reader the receipts?

Where are the reclassified cases and deaths in 1957 - 1959?

What the reader will see instead — as if it could possibly do anything but reveal that the real proof doesn’t exist — is a graph of Acute Flaccid Myelitis from 1990 or whatever. Often this graph is in absolute case counts, and a suggestion is made that “polio is going down while AFM goes up.” This is nonsense, since polio went down decades previously; and “AFM goes up” merely corresponds to increases in the number of children who are alive on Earth, not to polio reductions.

Serious (and unserious) answers to the question

A true, serious attempt to “prove” that polio declined due to reclassification would simply look at cases and deaths when polio declined. Anything else — sinister-sounding quotes, pathetic AFM graphs — is completely unsatisfactory.

Still, before showing what happens when such a serious attempt is made, I want to make it clear that this is no answer to unserious approaches to the question. That is to say, there will be some readers who see that the reclassification theory is devoid of evidence, and declare that this is irrelevant for some other reason — such as a totally incorrect notion that polio was declining naturally (it was increasing).

Such an argument is the same as saying, “The reclassification theory may be wrong on its own terms, a total gibberish fantasy concocted out of misleading quotes without proof, but it is right in spirit (because polio declines are fake for this other reason).” Very well — this still means the reclassification theory is wrong, regardless of the validity of any and all other arguments about polio declines. It offers nothing but misdirection and deception.

Focus on 1957-1959: Reclassification is not plausible

The reclassification theory tends to mine heavily from quotes in the Oral Polio Vaccine era, when no further epidemics occur in the United States. This, again, is unsatisfactory.

It must be demonstrated that reclassification is occurring (somehow) in 1955 - 1959, when polio cases and deaths are rapidly declining amid use of the Salk vaccine. This era allows for examination of what happens to reported cases when “muh lab confirmation” is applied to colloquially observed epidemics, which occurred in various cities after 1955.

By scrutinizing only later years, reclassification theory proponents rig the game in their own favor in key respects. Firstly, there is almost no polio, so of course lab confirmation will disqualify suspected cases and suspected epidemics. Secondly, the reader is not permitted to understand that lab confirmation once tended to verify the majority of cases investigated. Thirdly, the reader is confused (perhaps I should say seduced) into imagining that it would be possible to suppress colloquially observed polio epidemics merely by changing statistical requirements. This is not even possible; neither local public health authorities nor print and TV news could depend on per-100,000 attack rates for responding to or hyping polio epidemics, since those per-100,000 rates could not be tallied until the epidemic had passed.4 Epidemics as colloquially experienced (in local government and media) had nothing to do with statistics, but simply with patients showing up with paralysis.

Thus, we may consider an example from one of the several Salk-era urban epidemics, in this case Detroit, 1958.

Lab verification is mentioned in all of the papers regarding Salk-era epidemics, but cross-referencing the figures in such papers to US Public Health Service statistics requires mention of statewide case-counts, which as far as I could find, only exists for this epidemic.

Otherwise the Detroit example was typical for Salk-era urban epidemics, in that unvaccinated children were over-represented, resulting in an abnormally high portion of Black sufferers (the Chicago example has now been added to the footnotes of this post). Among the vaccinated, those with 1 or 2 doses contribute substantially to cases; the triple-dosed fare best. Severity appears to decline with number of shots. This is a sufficient depiction: The Salk vaccine was a sub-par product, but wasn’t nothing.

The following description was given for the lab confirmation program in use during this epidemic:5

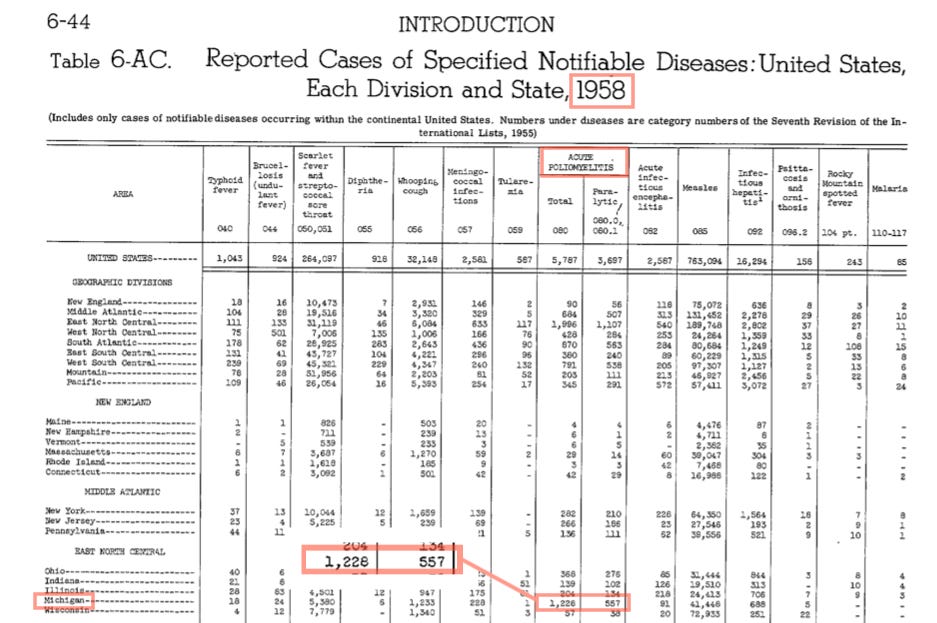

During 1958 the state of Michigan experienced its largest epidemic of poliomyelitis in many years, with more than 1,200 cases reported to the state department of health. […]

For several years the virus laboratory of the University of Michigan has performed diagnostic tests on specimens obtained from patients diagnosed as having poliomyelitis and has reported the findings to the hospitals that submitted the specimens, to the state department of health, and to the United States Public Health Service. Hence, prompt arrangements were made for the collection of stool and blood specimens as well as clinical histories on the cases occurring in 1958 as soon as the patients were hospitalized. Virological laboratory tests were carried out on 1,060 persons [869 stool, 191 serology], probably the greatest percentage of victims of a large epidemic of poliomyelitis ever to be subjected to laboratory investigation.

Two things can already be inferred. First, that even in a research report, a case-rate of 15.7 per 100,000 is sufficient to warrant the e-word (as far as I have found, only the Chicago epidemic of 1956 was described as an “outbreak” per the statistical novelties that are hyped in the reclassification theory). Second, that lab confirmation did not reduce reported cases — “more than 1,200 cases [were] reported,” which must include all 1,060 of those which were subjected to verification, regardless of result, as well as those which weren’t.

This is realistic. No published changes were made to US Vital Statistics case collection methods between 1950 - 1959.

Further, the wording suggests that as of 1958, such a complete verification effort — 86% of reported cases — was unprecedented. This is consistent with the wording applied to this and other urban epidemics. In this, “prompt arrangements were made” — meaning they had not yet been established in advance. Similar language characterizes the Salk-era case studies in Baltimore, Chicago, and Houston — lab verification is applied post-hoc, at the behest of the public health official or researchers writing the respective research reports; not as a result of a full-fledged and routine program being in place, even if the word “routine” appears.

Finally, the record for all US cases in 1958 confirms that no Michigan cases were “dropped” due to the aggressive and unprecedented lab confirmation effort.

But what if cases had been dropped in Michigan, 1958?

It is still of course revealing to inspect the percentage of cases which were lab-confirmed as polio. Because outcomes are more clearly reported in a separate paper, we may consider the results among 556 patients in the Herman Kiefer Hospital in Detroit. Among these, polio virus was recovered from 72% of paralytic cases and 20.2% of nonparalytic cases.6

The former value is consistent with nearly all paralytic cases being caused by polio virus. The latter — lab confirmation among patients with stiffness and inflammation, but not paralysis — is consistent with some cases being caused by other viruses, as well as some reduction of polio virus shedding among the vaccinated.

However one wants to interpret the results, there still would have been some hundreds of reported cases of polio in 1958, in Michigan alone, even if non-lab-confirmed cases had been reclassified (which they weren’t).

This is why the reclassification proponents must “rig the game” by only discussing lab confirmation after 1960.

Myriad lab confirmation “experiments” are available from before polio cases and deaths dwindled in 1960s — reclassification proponents cannot use any of these to support the notion that reclassification “caused” this dwindling, because they all find high rates of polio virus. (Two other examples were previously given in “The Polio Problem.”) Thus, reclassification proponents ignore the evidence from the era when polio epidemics actually occurred, and wave cardboard swords around in the eradication era from the safety of their oral vaccine cushion-forts.

Methods: Polio deaths truly declined after 1954 (no magic reclassification)

In graphical format:

Raw data, notes

Raw data is available on Google sheets.

Why not look at cases?

Immediately, the problem with investigating polio deaths is that annual numbers were not particularly high. It was not as a “killer” of children and young adults that polio was a problem worthy of the frenzy and terror it still inspires to this day — only, it can be argued, as an entity that maimed and crippled.

Only a fraction of paralytic polio cases wound up being reported as deaths; among white females, the average raw numbers for the pre- and post-Salk years are as follows:

But the simple problem with cases is that no relevant “alternate” causes were included in the Vital Statistics reports.

We can still ask, “Where did those 16,315 annual paralytic polio cases go?” Or even, “Where did those 4,162 annual paralytic cases from the first Salk years go?” The answer is limited to intuition, but this would seem sufficient: It is nonsensical to imagine that so many thousands of cases of what was known as paralytic polio could still have occurred annually in the US, unnoticed by doctors, the media, and the common man, simply because of lab results.

Just as the “toxin theory” requires reclassification to explain why polio actually stopped occurring after the Salk and Sabin vaccines, so does the reclassification theory require some alternate explanation (toxin theory or otherwise). Everyone, ultimately, knows polio really stopped.

Final notes on deaths

Above, raw average numbers are given for polio and the alternate causes in each age band. Most of the increase in raw numbers for the alternate causes can be explained by the baby boom — the 10-14 band is crashed by this crop of births in the latter half of the 1950s. Coincidentally, this band experiences an increase in alternate cause mortality that exceeds its large increase in population.

This increase is driven by roughly 5 average annual deaths in every alternate cause besides “other, nervous system.” Still, only 1 or 2 of these extra annual deaths is not explained by the population increase. This is trivial compared to the average reduction in 100 annual polio deaths. Reprinting the previous figure:

It can finally be noted that any given age band would not be convincing in of itself. It is the reproduction of the experiment in all age bands examined which satisfactorily demonstrates that polio mortality reductions do not correspond to proportional increases in mortality for similar causes. The at-the-time rather novel problem of polio cases and deaths increasing in younger adults is particularly “helpful” in expanding the sample available for this study.

To summarize the approach taken here:

Polio deaths are a rather delicate metric on a per-capita basis, considerably more-so than reported cases would be. Setting the denominator to all deaths among younger ages somewhat improves the resolution in this regard; removing some major causes which are not under suspicion helps to reduce noise. This allows for an investigation of whether the cessation of reported polio deaths corresponded to a proportional increase in reported deaths for similar causes.

It did not.

If you derived value from this post, please drop a few coins in your fact-barista’s tip jar.

Langmuir, AD. (1952.) “Usefulness of communicable disease reports.” Public Health Rep (1896). 1952 Dec; 67(12): 1249–1257.

In which, the chief epidemiologist of the CDC “confesses” that merely ignoring polio is not possible.

And so, as said, I have set out to rebuild the case that vaccines are not very relevant without needlessly getting the polio part of the story completely wrong.

The original version of this post was 400 off on the math here, in the direction opposite of my thesis; consequence of overwork.

Unless using annualized weekly rates, in which essentially cases are multiplied by 52. Had such an awkward and stupid standard ever been implemented by any local public health authorities, it would not have reduced epidemics — if cases still occurred at pre-1955 rates.

A more realistic picture of how health authorities would have responded to polio epidemics, had not the Salk vaccine reduced the incidence of the same, is given in the account of the 1956 Chicago epidemic.

In this case, the authors use the 35 per 100,000 incidence threshold to (retroactively) conclude that the epidemic was magically an “outbreak.” This linguistic tic — which I haven’t encountered in any other papers — has no relevance for the real-time response at the beginning of the epidemic.

What the reader will note instead are two meta-considerations that guide the response: There is an ongoing taboo regarding injection provocation; it isn’t explicitly mentioned in these quotes, but is the reason for the statewide requirement of special permission to keep using the Salk vaccine after an observed rise in cases, as well as for the collection of vaccination history of polio cases. This is appropriate; one can only say that the concern that Salk vaccines would, if poorly timed, increase paralytic polio during outbreaks should have been more explicitly acknowledged to the public, who obviously would have demanded that injections stop. The second consideration is that the authors — Chicago’s public health vicars — obviously see this outbreak as a chance to peacock their epidemiologic feathers. This is important for understanding how aggressive laboratory confirmation couldn’t possibly reduce polio epidemics — public health officials would have only sought to use it to reify and validate their own alarmist policies, just as testing served to do for SARS-CoV-2.

Bundesen, HN. Graning, HM. Goldberg, EL. Bauer, FC. “Preliminary report and observations on the 1956 poliomyelitis outbreak in Chicago; with an evaluation of the large-scale use of Salk vaccine, particularly in the face of a sharply rising incidence.” J Am Med Assoc. 1957 Apr 27;163(17):1604-19. doi: 10.1001/jama.1957.82970520003013.

Overview

This is a report on Chicago’s 1956 poliomyelitis [epidemic], in which 1,111 cases of poliomyelitis (835, or 75.2% confirmed paralytic cases and 276, or 24.8% confirmed nonparalytic cases), including 36 deaths, were reported in Chicago residents in the city of Chicago. […]

Launching the response — no lab confirmation, no incidence threshold. Just “some cases happened.”

However, with the reporting of 13 more cases during the week ending June 28, we became aware of a sudden increase in the number of reported cases in Chicago. This awareness was based on a comparison of the 13 [mentioned cases] with the 2 cases reported in the comparable period of 1955.

Because of this we were desirous of vigorously intensifying our inoculation program. However, to continue our inoculation program, it was necessary that permission be obtained from the Illinois Department of Public Health, because of a directive dated May 25, 1956, which stated, “Inoculations with poliomyelitis vaccine can be continued into the summer until there is an increased prevalence of the disease. . . . Specific recommendations will be made for local areas with high incidence if indicated.” Hence, the Chicago Board of Health on July 2, 1956, transmitted to the Illinois Department of Public Health complete information as to the sudden increased prevalence of poliomyelitis cases in Chicago at that time with a request that a recommendation be provide permitting our continuation of poliomyelitis inoculations.

While awaiting this recommendation, one of us (H. N. B.), cognizant of the possible urgency of the situation, began to mobilize the total facilities under his direction [etc….]

Real-time case response: No reference to lab confirmation

The major problems facing the Chicago Board of Health were as follows: […]

To mobilize the personnel of the Chicago Board of Health at once into a well-integrated team, personnel being placed on a seven-day week, emergency basis, with all vacation and other leaves being canceled.

To aid in the coordination of the activities and the integration of the facilities of medical groups […]

To insure the immediate hospitalization of persons with suspected or confirmed acute cases of poliomyelitis as they were reported and to arrange for the later hospital care of the persons with acute cases in private hospitals after the acute stage had passed. (In this outbreak, 70% of all persons reported as having poliomyelitis were hospitalized in the Chicago Municipal Contagious Disease Hospital and 19% in the Cook County Hospital, 11% either were hospitalized in private institutions (7%) or their cases were not diagnosed and reported until after the acute stage was well over (4%).) […]

To evaluate at once the outstanding demographic characteristics of this outbreak, which were its presence predominantly in (a) children living in densely populated, lower socioeconomic areas, (b) the nonwhite population […]

Two weeks into the response: mobilizing lab verification post-hoc with “special provisions” — but no retroactive reduction of the cases already counted and hospitalized, nor of future cases

On July 16, 1956, representatives from the Public Health Service, Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; the Illinois Department of Public Health; and others met in Chicago to develop procedures jointly for obtaining as accurate and complete epidemiologic information as possible concerning every reported case of poliomyelitis in 1956. The data to be collected included the exact date of onset, paralytic status, history of previous tonsillectomy, clinical course, and the ultimate outcome of each case. Arrangements were also made for obtaining complete information as to any history of poliomyelitis vaccination, dates and site of vaccine inoculation, the site of first paralysis, if any, and its degree. Special provisions were also made for collecting and examining all necessary laboratory specimens from the patients. The Illinois Department of Public Health laboratory performed all of the routine diagnostic blood and stool cultures on these specimens submitted by the board of health.

Returning to the overview, we confirm that this post-hoc lab verification campaign made no difference to final case counts:

Of the 1,111 cases, virology reports have been received on 651. Of these 651 cases, a poliomyelitis virus has been successfully isolated from 412 [63.3%]

There is no way to imagine that implementing a just-in-time lab confirmation program (totally off the books) could, in future years, have made it so that 800 people became paralyzed routinely in the summer but no government or media response followed — especially if 2/3 of them would come back positive for polio virus anyway.

The only way to prevent observation of polio epidemics is to prevent occurrence of polio epidemics. The reclassification theory is idiotic.

Brown, GC. Lenz, WR. Agate, GH. (1960.) “Laboratory data on the Detroit poliomyelitis epidemic-1958” J Am Med Assoc. 1960 Feb 20:172:807-12. doi: 10.1001/jama.1960.03020080037010.

Molner, JG. Agate, GH. (1960.) “Final report of poliomyelitis epidemic in Detroit and Wayne County, 1958.” Public Health Rep (1896). 1960 Nov;75(11):1031-43.

Thanks for this, it’s very interesting. Forgive my scatter gun of questions and if I’ve missed these details in preceding posts….!

Was it just the Salk (injected) introduced here? I don’t know when Salk v Sabin were used ( also I’m English and probably have seen data relevant to what we used here which may have been different) but have the general impression that Sabin (oral) should be more effective.

I understand that there are three strains of polio; does Salk cover all three and does Sabin cover all three?

Am I correct thinking a Salk vaccinee could still get the infection and shed it, but suffer less severe consequences for themselves?

Is it also correct that a Sabin vaccinee should be able to resist getting infected ( against the strains in the vaccine) in the first place and therefore not be a risk of shedding to others, except for the fact that during their initial exposure to the Sabin they can shed the vaccine strain ( which occasionally might dis-attenuate back to a dangerous version)?

In general my thinking has gone like this. Prior to 2020 I believed all vaccines worked except for occasional people with unusual immune systems and a tiny minority experienced some rare side effects ( of which death wasn’t one). Now I believe all vaccines have side effects in a much larger percentage than I was led to believe ( including death) and that some vaccines work and some don’t. But this is complicated by the fact that a vaccine working at one point in a persons lifetime doesn’t necessarily benefit them for their whole lifetime or benefit society as a whole as it changes the pattern of infection. Thinking in terms or risk/benefit ratios is determined by efficacy and prevalence.

The question that bugs me personally the most is that of meningitis vaccines (ACWY, Men B, HiB). I have a vague recollection of seeing a video presentation showing two studies that demonstrated benefit for 8 months or two years, but I can’t remember if that was for young children or teenagers. I also have a memory of it being shown that HiB vaccination reduced HiB meningitis in young children. Meningitis was the only serious infectious disease I saw as a junior doctor doing paediatrics, general medicine ( young adults only) and as a GP where patients were seriously injured or died. I saw one a month in paediatrics, one a week in general medicine and one case in 4 years as a GP.

Thankyou for this, it's very informative. I recall seeing some years ago some information about correlations between polio symptoms and the use of pesticides at the time of 'outbreaks' which occured in geo and temporal proximity. Unfortunately, I did not keep the information. Is this something that you have come across before?