The polio toxin theory, pt. 1

Claims that polio was caused by toxins (e.g. pesticides) have obvious flaws.

Polio series table of contents:

The following standalone treatment of the “polio toxin theory” is necessary only because of the great level of attention and interest the theory generates. Since the polio toxin theory is nonetheless nothing more than a distortion and a fantasy, this post is ultimately a supplemental discussion to the real question of what caused polio epidemics, and the real answer, which is provided here:

Explaining Polio, pt. 1

Note: the previous post (“What polio was not”) has been updated to address the question of whether the polio epidemic enigma was simply over-reporting of a previously unnoticed rare problem (it wasn’t), or mis-treatment (it wasn’t). Summary: Polio epidemics were outbreaks of paralytic illness caused by an increase in latent susceptibility to seasonal poli…

(Finally, note that the topic of “reclassification” is addressed in a wholly separate post; the focus of this post is why toxins don’t explain polio.)

i. Polio Skepticism in Context

Following what I presume, but still have not read to confirm, is an erudite review of the flaws in most vaccine research and recommendations, the book Turtles All the Way Down veers into a choleric, sprawling tirade against the case for the great polio epidemics of the 20th Century having been caused by a viral infection.

If Wickman had stamped polio as “contagious”, Landsteiner was the one who classified it as “infectious”. The purported “isolation” of the virus by Landsteiner wedded polio research to the idea that a virus was its causative agent.

This I believe fairly sums up the view Turtles purports to take regarding the polio virus theory: It was a castle of idiocy built on a handful of obscure premises that were never re-tested or re-interrogated. No one thought to consider the obvious alternatives.1 The whole default narrative meanwhile rested on three crafty legalistic fabrications, because the illusion couldn’t “get by” without those foundational magic tricks.

This post seeks to provide the reader a quick intuition calibration regarding the plausibility of the alternative proposed by the Turtles authors — toxic pesticide use in American farming. To justify my abrupt treatment, first, I would like to put skepticism of the default virus theory into context.

This skepticism, and the peevishly dogmatic but affronted attitude which accompanies it, is not new; besides being aligned with “Virus Trutherism” (or “Terrain theory dogmatism”) generally, it has attacked the consensus view of polio research since the very first successful inoculation of monkeys.2 And as late as 1950, shortly before the vaccines expunged the disease from popular obsession, environmental toxicity was one of 13 “Popular Causes” and “most prevalent superstitions” regarding polio paralysis targeted3 by the National Foundation for a run of “fact-checking” newspaper stories.4

And so in 1916, when the children of New York City were in the grips of an extraordinarily deadly paralysis outbreak, an out-of-towner sent the following bitter scolding to the Brooklyn Daily Eagle:

The craze for “mystery,” “germs,” “serums,” and what not seems to be the only thought actuating the popular mind, and simple and effective means of treatment are lost sight of. Either Dr. Lee is a fool and totally without true medical knowledge or else his article should be printed in large type in every paper in New York, for is the first piece of absolute intelligence I have seen since this epidemic started.5

“Contagious,” “infectious”, “isolation,” sneers the modern skeptic; “mystery,” “germs,” “serums” sneers the skeptic in 1916. Why not simply get wise to the down-to-earth wisdom of Doc-tor Lee?! Well, just what is it that Lee had previously written?

“Child fevers are symptoms of mismanagement in child feeding and neglect in caring for their bowels,” he says. “It is a disease caused by filthy blood and clogged bowels, and the proof of it is that the cases occur at any time, any place, and here or there, according as nature is damaged to a particular degree in a given child or adult, and from which diseased condition children have brain and spinal cord fevers.” […] “I see the evidence that it is a self-generated disease, for by clearing the intestines of feces at the start nearly every case quickly recovers normal health.”6

In case of the early onset of polio, before paralysis, Lee’s remedy might have value. Polio virus replicates at first in the digestive tract.

But his view of the etiology — “mismanagement “in child feeding — is totally contradicted by the demographics of which kids would become paralyzed. Over and over, researchers of early epidemics remarked on the lack of protection afforded by affluence — “fashionable suburbs suffered equally with crowded slums,” as a summary of the 1908 NYC epidemic describes.7 Lee’s theory flies in the face of so many observations like that which followed a press tour of the polio ward of Manhattan’s Willard Parker Hospital in the same month:

Two striking impressions received from the visit were the indefatigable optimism of the little ones and in their prevailing physical and mental excellence. The statement of epidemiologists that infantile paralysis has a preference for healthy children has been emphatically borne out in the present epidemic. As the newspaper men passed crib after crib, each holding a child 4 or 5 years old suffering from the disease in some form, they saw only children otherwise strong in body and above normal in mind.

This example, from a hundred years in the past when far less evidence existed to support the virus theory, hopefully serves to show how a confidently and disdainfully expressed “simple solution” to the polio mystery can so easily be exploded by a single trivial detail regarding actual observations of illness. Authors of crackpot theories regarding polio — and this is not a pejorative, for I have my own on the subject — can easily impress the reader with deficiencies in the virus theory, or with portrayals of the virologists at Rockefeller Institute and elsewhere as conniving wizards casting spells over the lay imagination — but they will seldom disclose the deficiencies with their own alternate explanations. This does no one any service, save of course the same authors.

It is thus the main objective of this post to illustrate briefly the details that contradict the Pesticide Theory advanced by Turtles’ polio chapter.

Once done, some general critique will be offered on the rhetorical approach of the book on this subject.8

This segues into a final comment on context. The idea that polio was caused by a virus — of any kind of infectious agent — was beset from the start by hostile doubt for a reason: It is inconsistent with the distribution of paralytic cases in space. But it was consistent, and this is the key point, with the distribution in time. By failing to grant this virtue, and overtly denying it on several occasions, the Turtles polio chapter cannot be called a charitable critique of the default theory. It neglects to present to the reader the most critical elements of evidence on the side of the defense, merely cherry-picking the weakest or most nuanced elements to performatively pummel with objections alternately fair or duplicitous. It is a disappointing work, because it is intent on simply overwhelming the reader into confusion with a million details rather than dealing directly with the most critical evidence in the case.

ii. The Pesticide Theory, and its most obvious flaws: Symptoms, Timing & Immunity

Turtles proposes that polio epidemics resulted from exposure to two pesticide technologies widely adopted in the United States — lead arsenate in 1893/4, and DDT in 1944/5.

In doing so, it aggressively effaces the clinical picture of polio, proposing it as “just another paralysis” that couldn’t possibly be distinguished from lead / toxin -induced nervous system damage. We’ll set this ploy aside until the critique below. For now, it suffices to propose that there was some condition called “polio paralysis” that was observed in the United States after 1892, and that the authors of Turtles have proposed the same condition resulted from exposure to toxic pesticides on agricultural produce.

The problems are immediately obvious.

Symptoms

In short, polio was too specific a disease to have resulted from “poisoning.” There is no plausible explanation for how exposure to a toxin could result in such a “sniper-like” blow to the motor neurons, leaving higher-order functions spared.

As already quoted above, children stricken with polio were, immediately after the acute phase, frequently observed to be of sound mind and good cheer, and more physically hale than would be expected. (Of course, this extremely frequent observation, repeated over years and years, isn’t even mentioned in Turtles.)

This is inconsistent with neurological poisoning, when mental and emotional disturbances are often the first symptoms.

In the case of lead poisoning, for example:

Children who survive severe lead poisoning may be left with permanent intellectual disability and behavioural disorders. At lower levels of exposure that cause no obvious symptoms, lead is now known to produce a spectrum of injury across multiple body systems. In particular, lead can affect children’s brain development, resulting in reduced intelligence quotient (IQ), behavioural changes such as reduced attention span and increased antisocial behaviour, and reduced educational attainment. Lead exposure also causes anaemia, hypertension, renal impairment, immunotoxicity and toxicity to the reproductive organs. The neurological and behavioural effects of lead are believed to be irreversible.9

Supposing that polio paralysis results from a particularly high dose of whatever toxin, either in a single dose or by chronic exposure, it should not somehow be the case that the neurological functions usually harmed first are then harmed least.

This suffices to give the reader a picture of the toxin theory’s problem with symptoms. (Obviously one could go on, but a single problem is enough.)

Within the nervous system, expression of CD155 (the polio virus receptor) during embryogenesis is limited to the same anterior horn motor neurons destroyed in cases of polio paralysis10 — thus explaining the “sniper-like” accuracy of polio’s neural injury.

Timing

The Pesticide Theory is seemingly nifty with regard to the annual record. This will be further discussed in section iii.

It leaves would-be believers baffled, however, when it comes to the pattern on the calendar. Polio outbreaks occurred in summer and early autumn. Yet the Turtles authors claim:

Dr. Charles Caverly, president of Vermont’s State Board of Health, reported that most of the cases occurred between July and September. Similar to Massachusetts, apple orchards were also very common in Vermont, and the harvest season coincided with the timeframe of the polio outbreak reported by Caverly. […]

Epidemics peaked during the harvest season,

Regarding the earliest polio outbreaks in Massachusetts and Vermont, Turtles is particularly insistent on the treatment of apples; and this is consistent with the earliest experimental use of lead arsenate in 1893 (with product manufactured in Boston, and trialed in Boston and Amherst).

This is a poor fit for polio.

First of all, spraying lead arsenate peaks in advance of “harvest season,” as the goal is obviously to protect produce while it is growing.11 Insects become active as soon as spring brings warmth, and this is when pesticide spraying begins. Setting aside increased vulnerability to acute exposure to lead among young children, it is improbable that lead-induced paralysis would rather magically not have resulted in outbreaks among a substantial number of older farm workers, resulting in “misdiagnosed” polio outbreaks in the spring.

Spraying lead arsenate continues throughout the summer; any given field or orchard may have several sprayings throughout growing season; but again, if spraying is the problem, then “misdiagnosed” polio should not peak in summer but be continuous starting from the spring.

This leaves “harvesting.” Apples are harvested particularly late, well into high autumn, i.e. October. It is true that polio outbreaks occurred sometimes in October, including in 1916 in Massachusetts.12 But these were exceptions to the rule that polio strikes in summer and “early autumn.” In 1949, a busy polio year, Massachusetts marks the peak of cases in late August.13 Similarly, in the first Massachusetts outbreak highlighted in Turtles, featuring a mere 26 cases in 1893, the epidemic falls in summer and early autumn.

If DDT (and / or lead arsenate) is the problem, and if “harvesting” produce is the means by which pesticides are producing “misdiagnosed” polio, is summer and early autumn seasonality really what we should expect to see?

Lead arsenate, once eventually embraced by farmers, was sprayed on essentially all produce.14 It is certainly fair to propose that more types of produce were “harvested” in polio seasons, even if this requires assuming that spraying was somehow at the same time (or rather, weeks and months earlier) not at all a hazard to workers. But this only satisfactorily explains the presence of polio in the summer, leaving utterly mysterious the absence of polio in later autumn. Particular types of produce, including apples, are annually harvested up to and throughout October — the Pesticide Theory can offer no explanation for why polio is rarely observed so late into the year.

Canada serves as a striking example of a historical mismatch between polio and “harvesting”, although the following graph uses four-week intervals instead of months:

Polio surges in Canada during mid-season — are Canadian children simply that eager to inspect their future canola?

Common sense RE timing

It challenges the intellect to imagine how contact with poisoned food could cause disease without being noticed by the afflicted. One generically imagines that the phenomenon of “kids all touched some apples; kids all got sick” isn’t elusive to human perception.

In lieu of solving this problem, Turtles rather blurrily proposes that the diffused notion of “harvesting” (but not spraying) lead arsenate and DDT-treated produce is plausibly responsible for whatever observations of paralysis might occur around the same time. It conjures a “polio-making machine” to have been in operation, in which pesticides are imputed in one end, question-marks whirl about behind the panels, and polio pops out on the other end in “harvest season.”

This isn’t the case. If the observed polio epidemics in question were caused by “harvesting,” then polio ought regularly to have been considered a disease of autumn. That it was a disease of summer and early autumn, and rarely high autumn, tells us that polio stopped happening in most places by September. Further, the common observance of a peak in July corresponds to a nadir in both probable spraying and harvesting of all types of produce.

The above image uses Connecticut as an example; earlier we examined Canada. These are just two of many exceptions to a “harvesting” seasonality in the north (to keep the focus on lead arsenate). Meanwhile, we have acknowledged that Massachusetts sometimes fits the “harvesting” pattern (but sometimes does not) — but if the case for the Pesticide Theory depends on cherry-picking a few fits out of a million exceptions, there is no case at all.

Not DDT

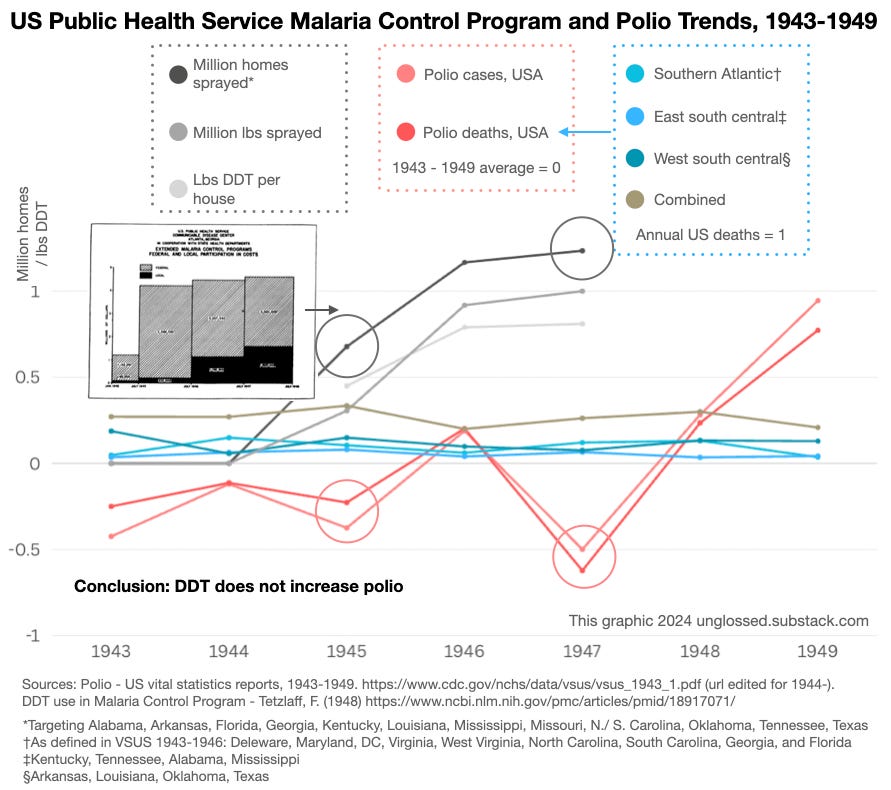

There are, at last, a host of little details that deflate the notion that the advent and rapid adoption of DDT is responsible for the post-War increase in polio cases. Perhaps the best way to interrogate this theory is to focus on the five years immediately before and during the Federal Malaria Control program, which resulted in the widespread dispersal of DDT directly into millions of American homes. In essence, this program was a nationwide natural experiment for the Pesticide Theory (spraying was focused on whichever counties across the country had high rates of malaria).

As seen above, the US Public Health Service Malaria program ramps up in 1945 — ostensibly therefore the year the Pesticide Theory should pin its claims upon (though Turtles is vague in this regard). Saturation per house increases every year of the program. This program, which would have outpaced the sporadic adoption of DDT for agricultural purposes in the same years, falls pat atop the post-War trend of increasing polio cases in the United States (and elsewhere, which is a problem for the Pesticide Theory, but never mind).

It therefore seems obvious that such an all-out chemical warfare program aimed at the American home should have resulted in a veritable explosion in “misdiagnosed” polio paralysis, if pesticides are really the secret culprit of the disease.

We can thus look for increases in both overall polio and the share of polio in southern states which were targeted by the Malaria Control DDT campaign from 1945-1948. But those increases are not there:

More problems with the theory that DDT caused polio appear in the era of the Salk vaccines, when many American cities initiated suburban DDT tree-spraying campaigns to combat Dutch elm disease, directly exposing residential areas to the chemical. DDT was shot from canons or dumped by aircraft, yet polio continued to decline everywhere. These examples are discussed in Pt. 2.

Finally, immunity

The immunity following an attack of poliomyelitis appears to be of long duration. It is not yet known whether repeated subclinical infections are necessary to maintain the state of immunity. Considering the age distribution of cases, this seems unlikely. Although not unknown, second attacks of paralytic poliomyelitis are rare.

—JHS Gear, “Recent Advances in Poliomyelitis,” 194915

Of the two “major” flaws with the Pesticide Theory, it was helpful to focus first on timing, because it allows the introduction of a general picture of the theory’s claims and what was really experienced during the polio era. It spares the reader from having to wade through a full, careful introduction to the problem.

But immunity is by far the most fundamental flaw with the theory.

Pathology is one part of the defining nature of polio, and it will be discussed in section iii. The other is seasonality — the phenomenon of epidemics — and this way of “defining” polio suffices for the discussion of immunity.

It was observed after 1893, and especially after ~1905, that (mostly very young) children would experience paralysis in summer and early autumn in regional clusters — proportionally only a small number of them, but in some years nonetheless quite a few in absolute terms. In rural areas, paralysis affected somewhat older children, and adults; and epidemics were more infrequent upon any given inch of dirt, vs. northern cities.16

Seasons featuring many cases in a region could be termed “epidemics,” and cases within those seasons were classified as “polio.” Yes, sometimes erroneously — it is plausible that any case of paralysis for a different cause than “the cause of polio epidemics” might have been reported as a “case” in jurisdictions that required such reporting. Nonetheless, since polio epidemics were not being observed and declared around the clock — 12% of overt diphtheria cases annually were followed by a short bout of paralysis,17 but no one will claim that this was the mystery agent behind polio epidemics, since diphtheria struck in the winter — and so long as our concern is what caused them and the cases occurring within them to be observed, we do not care about whatever is “mistaken” for our mystery ailment. Only that which causes the rash of cases.

The Pesticide Theory alleges that exposure to lead arsenate pesticide, beginning in 1893, is the cause of these epidemics of paralysis, and thus of a great number of the observed cases in any given epidemic (again, it does not matter whether some cases are caused by something other than our principle agent, whatever it is).

How, then, could it be the case that previously “pesticide-poisoned” children were continually observed to be immune from later paralysis?

Here, it must be candidly acknowledged that the immunity after overt paralysis was not methodically studied, in part because it was recognized early on that older children were usually at low risk of the disease. Flexner remarks in 1916 that “Infantile paralysis is one of the infectious diseases in which insusceptibility is conferred by one attack”18 — but this claim is made based on neutralization tests with overt and abortive convalescent patients (the latter referring to flu-like illnesses in households with concurrent paralytic cases); 1916 was obviously too early in the polio era to be sure of durable natural immunity on a any true empirical basis.

Nonetheless, the inference of immunity in the early era is sound given that in the post-War era, rare cases of repeat overt polio did attract comment (in the context of discerning the three different serotypes of the virus). By then, natural immunity was still typically inferred based on antibodies appearing after overt and abortive cases (and found to be present in almost all older children and adults), and the rare repeat attack attributed to encounter with other serotypes later in life.

We discussed the possibility of alteration in virulence as well as changes in immunity of individuals [over the years] and the fact that there are several types and varieties of poliomyelitis. […]

The only available weapon against poliomyelitis at the present time is natural immunity. It was pointed out by J. H. S. Gear of the South African Institute for Medical Research that if children are infected with the poliomyelitis virus, they can develop natural antibodies effectively and rapidly and with a relatively small amount of paralysis. In this way an immunity is developed. With modern hygienic measures children are protected against virus infection and thus they are prevented from developing an immunity during childhood. As a result, we are seeing more poliomyelitis in adults.

— Emil DW Hauser, Second International Poliomyelitis Congress, 195219

The above quotes are not to bully the reader with “rah rah experts virus certainty,” but rather oppositely to offer a glimpse of the tentative understanding of post-infection resilience to future paralysis — one that depended largely on inference, given that immunity seemed far more widespread in those who didn’t develop paralysis during childhood than those who did. In fact there was a long-standing controversy on this topic, when it comes to the majority of individuals who are not paralyzed, that lasted until the advent of vaccines. The same controversy however would not have lasted even if counter-examples to immunity were at all common within those who became overtly paralyzed. Instead, as Gear says in 1949, they were rare.

Put differently

A substantial number of researchers — even if not often the luminaries in polio research — questioned the supposition formulated by Frost in 1913 that the resistance of older children and adults to polio, whether observed by low rates of paralysis or antibodies, reflected true natural immunity resulting from viral infection — as opposed to some innate resilience that develops with age. In other words, this element of the polio mystery led to widespread attacks on the entire notion of antibodies (blood neutralization of virus in animal models) as an immune marker.

Had it been the case that previously-paralyzed children were also not immune after their first instance of polio, this observation would have been used to settle the debate immediately in favor of innate resilience.

We can therefore safely take the lack of widespread comment regarding repeat paralysis cases any time from 1893 - 1954 to mean that such observations were extremely rare.

This likewise applies retroactively to the Pesticide Theory: If this were correct about innate susceptibility, the same researchers who held this belief before 1954 would have pointed out examples of common repeat paralysis cases.

Even an imperfect picture of natural immunity such as was left by the record of early research is thus a profound problem for the Pesticide Theory. How, exactly, could the children afflicted by poisoned apples who are discharged from the Willard Parker polio ward back to their homes in 1916 be prevented from returning the next “harvest season”? Wouldn’t they in fact be the most susceptible?

Turtles is in fact quite insistent that the individual susceptibility of children to pesticide toxicity explains the Russian Roulette nature of polio:

[The Pesticide Theory] can also accommodate any pattern of familial morbidity – isolated cases, multiple cases, or simultaneous occurrence – since symptom severity would be influenced by the level of exposure and the individual’s specific sensitivity to the toxic substances consumed.

Yet as early as 1916, Flexner writes

Of those who survive a part make complete recoveries, in which no crippling whatever remains. This number is greater than usually supposed […] The disappearance of the paralysis may be rapid or gradual—may be complete in a few days or may require several weeks or months.20

The onus is certainly on the Pesticide Theory to explain why there are so few observations of repeat paralysis before the 1940s; and even then only rare cases.

What is the reader to imagine prevents a “sensitive” individual, once recovering from their poisoning with lead arsenate or DDT, from falling ill from the same poison again the next epidemic?

Especially if the DDT has been sprayed directly into their home?

The Forgotten Vaccine Triumph: 1935

It may finally be remarked, regarding immunity, that the Pesticide Theory relies heavily on manufacturing an alternate explanation for the disappearance of polio epidemics after the advent of the polio vaccines. Why, in other words, when children were all vaccinated for polio virus, were the pesticides secretly responsible for causing observed outbreaks of paralysis before, suddenly not doing so after?

The manufactured explanation which is provided will be revisited again as one of the “minor flaws” — instead, I would point out that immunization based on the virus regarded as polio was achieved with apparent success in 1935.

In fact, though it could not have been known at the time, the eventual majority of all-time cases of polio in the US and elsewhere could have been prevented by any crude inactivated vaccine based on a strain of the virus maintained through serial monkey passage, given that this strain corresponded to the serotype responsible for nearly all cases.21 Given that the Salk vaccine was found protective simply by hindering viremia, it follows that even a vaccine made from infected monkey tissue would have been effective as well (perhaps even cross-protective against all three serotypes). Why wasn’t such a vaccine deployed?

The canonical explanation is that one was tried; it was a failure and caused polio in recipients; the young researcher responsible committed suicide a few years later in remorse.

This is a fantasy. In fact, the vaccine developed by the young Brodie and aging Park was by all appearances a success.

Up to the present more than 9,000 individuals have received vaccine. In asmuch as more than 7,000 of these were in endemic or epidemic foci, it is quite likely that they were exposed to the virus. The control group, of non-vaccinated children consists of about 7,500.

Of these approximately 4,500 were in exposed areas and can be compared with the similar group of 7,000 vaccinated. In so far as possible each vaccinated individual was matched with a control in the same district and of the same age. Wherever possible playmates were used.

Up to the present, [potentially 1] of the nearly 7,000 who were probably exposed, after vaccination with fresh vaccine was completed, have contracted the disease, whereas 5 of a smaller control group have come down.22

This is a somewhat limited dataset for such a rare disease as overt polio — obviously, the Salk and Sabin trials were much larger. But the results are encouraging, and given what we know now regarding the Salk vaccine, there is no reason to interpret this as anything other than an early “replication” of the later result, since the method of creating the vaccine was similar enough. Brodie and Park therefore seem merited in concluding:

Field studies on at least 50,000 more children should continue in order to reach a positive conclusion.

So what happened? Put simply, the (probably worthy) 1935 vaccine was tanked by pique and coincidence.

A simultaneously trialed vaccine by Kolmer did appear to cause polio, perhaps at a rate not too different from natural exposure to the virus — and this isn’t surprising, given that it was “attenuated” be entirely fanciful means.23 The Brodie/Park vaccine, formalin-treated exactly as the Salk vaccine eventually would be, did not set off any such signals. But as both endeavors were affronts to Simon Flexner, the latter project was pilloried at the same meeting where Kolmer’s product was reviewed.24 Firstly, the projects had been funded by de Kruif, a former Rockefeller Institute researcher fired by Flexner for criticizing medical research practices in print. Secondly, the positive results obtained by Brodie and Park contradicted the results obtained by similar vaccines in the inappropriate monkey infection model. In other words, evidence that didn’t fit the “default” understanding of polio pathology was dismissed — in penalty of a probably effective vaccine.

Despite substantial publicity regarding the Brodie/Park trials in areas experiencing epidemics at the time, no outcry followed the spiking of their dream cure. This isn’t so puzzling given that aside from the National Institute’s successful propaganda and fundraising campaigns, polio was not a pressing issue in the Depression-era public’s mind. The toll would be paid later.

By the Salk era, Flexner’s “default” understanding — that the virus passed from the nasal cavity to the brain in humans — had been replaced by a theory in which the virus accessed the nervous system through the bloodstream. It made absolute sense in such a context that an injected vaccine would provide protection against paralysis.

And this, again, is exactly what was already suggested by Park and Brodie’s results in 1935. But by then, both were already dead.

Nonetheless, their trial provides a time-stamped “proof of concept” for the Virus Theory which totally evades the counter-explanations the Pesticide Theory uses to explain the success of the Salk (and Sabin) vaccines. Exactly why is it that the 7,000 individuals vaccinated in epidemic areas were “immune” to the scourge of lead arsenate in 1935?

In Pt. 2: The polio vaccines worked

In Pt. 3 (not yet published): Some minor flaws, and a critique of the rhetorical approach in Turtles.

If you derived value from this post, please drop a few coins in your fact-barista’s tip jar.

In fact, plenty of people thought of the alternatives, including toxins. Readers in 1916 volunteered to the New York Health Department every theory under the sun to explain the explosion in cases that summer, including “earthquakes and volcanoes; […] white clothing and excitement due to glare, autos and water reflections.”

“Paralysis Cases Rapidly Fall Off.” New York Herald. August 28, 1916. p 7. newspapers.com

See if for some reason desired, Frost, WH. “Poliomyelitis: Is It of Germ Origin?” Buffalo Med J. 1911 Feb; 66(7): 392–395.

Rightly or wrongly, as the reader might have it.

“‘13 Against Superstition and Fear’ Debunks 13 ‘Popular Causes’ of Polio.” Fitchburg Sentinel. January 13, 1950. p 1. newspapers.com

“Many Views on Paralysis Problem Expressed in Letters to The Eagle” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. August 24, 1916. p 2. newspapers.com

“Says Feed Children Right; No Paralysis.” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. August 22, 1916. p 11. newspapers.com

“Acute Poliomyelitis in New York.” Hospital (Lond 1886). 1909 Jul 31; 46(1199): 459–460.

As of mid-January, I have yet to get around to writing this.

Gromeier, M. Solecki, D. Patel, DD. Wimmer, E. (2000.) “Expression of the Human Poliovirus Receptor/CD155 Gene during Development of the Central Nervous System: Implications for the Pathogenesis of Poliomyelitis.” Virology. 2000 Aug 1;273(2):248-57.

Various newspaper advice stories and reports circa 1894-1920.

Lavinder, CH. Freeman, AW. Frost, WH. “Epidemiologic Studies of Poliomyelitis in new York City and the North-Eastern United States During the Year 1916.” p 164.

“Polio Cases Drop; Throat Surgery Possible Soon.” The Boston Globe. October 3, 1949. p 5. newspapers.com

Again, various newspaper advice stories and reports circa 1894-1920.

Gear, JHS. “Recent Advances in Poliomyelitis.” Postgrad Med J. 1949 Jan; 25(279): 3–8.

The common impression, before the 40s, that polio was more prevalent in rural populations was a result of only noting those epidemics which did occur, not all those which did not. Aycock remarks in 1931, “The idea of rural preponderance of cases of poliomyelitis has gained emphasis more from the striking occurrence of the disease in remote localities far removed from other cases than from adequate statistical analysis. As a matter of fact, the total incidence of poliomyelitis in the registration area of the United States since the disease was made reportable shows and urban-rural ratio approximately the same as that of measles.”

Aycock, WL. “The Poliomyelitis Problem.” Cal West Med. 1931 Oct; 35(4): 249–255.

Crum, FS. “A Statistical Study of Diphtheria.” Am J Public Health (N Y). 1917 May; 7(5): 445–477.

“Dr Flexner Tells How Plague Grows.” The Sun and New York Press. July 14, 1916. p 4. newspapers.com

Hauser, Emil DW. “The Second International Poliomyelitis Congress.” Q Bull Northwest Univ Med Sch. 1952 Spring; 26(1): 65–67.

(“Dr Flexner Tells How Plague Grows.”)

The original version of this post incorrectly said that the strain in question did not correspond to the most common wild strain (Type 1), even though this hurt my argument. However, I realized afterward that it almost certainly must correspond to Type 1, or successful monkey inoculations from human cases would have been far less common.

The typing project led to such a rapid change in research terminology that detailed translations of old and new strain identifiers is difficult to locate. Finally, I just asked Chat-GPT which type corresponds to the Flexner strain.

“Infantile Paralysis Vaccines Discussed” St Louis Post-Dispatch. (November 20, 1935.) p 10. newspapers.com

Kolmer points out in the St Louis meeting that none of the post-vaccination cases occurred after the full course of 3 doses. This is a strong sign that the “vaccine” immunized, but was not truly “attenuated.” In the end the difference between an attenuated polio (like Sabin’s) and the regular virus is just a rounding error.

Brodie, M. Park, WH. “Active Immunization Against Poliomyelitis.” Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1936 Feb; 26(2): 119–125

I need to reread this a few times, but something I've been thinking about is that there appears to have been a large era where misdiagnosis was occurring and that scientific evidence was heavily muddied, but rather than consider that there's so much information out there that may not be accurate given limitations at the time, it seems like we're milking hypotheses out of whatever we can draw.

I mean, even when writing about my black widow post there were comments that the abdominal pain and symptoms following a bite led to unnecessary surgeries. There's a ton about medicine that was not known at the time, and even now there's a ton that's still not known. It's sort of weird that we consider that we have reached some precipice in medicine/science and that we know all there is to know.

If it's true that some polio vaccine campaigns, such as the ones of Bill Gates, caused some polio, it would also be odd if they did not contain DDT, or, assuming they also have only typical adjuvants, why other vaccines containing the latter don't seem to produce polio (enough to be noticed).