Those blasted antivax... migrants?

There is no such thing as a measles "emergency": Measles carries risks... but so does regular life

RE low activity

It has been a slow week, with my time divided between thinking about political subjects and teaching myself how to remove tattoos with a laser I bought on ebay.

It is in fact a very simple and easy-to-master topic, and the lasers use standard plugs. Thus as far as hobbies go, the barrier to entry is almost non-existent.

Yet in California, commercial tattoo removal must be performed by or under the direct supervision of a licensed medical doctor (!). As such, treatment is abusively expensive — the customer must compensate the doctor for wasting their time shooting a bunch of skin with light from a machine that can be operated with about as much up-front training as a forklift. Since laser treatment is repetitive, requiring 6 to 20 sessions, it is not surprising that one can buy their own machine for a fraction of the money it costs to pay a doctor in California to use it. Yet there is very little evidence that anyone has done this — I may post a guide.

I have two tattoos, both acquired on a whim on the way home from work during a busy month in 2017; this was about the time that tattoos no longer were a “statement,” and therefore I could indulge the curiosity about the experience of being tattooed, without signaling insecurity or angst or any such thing. Answer: It is fun to get tattoos. However, one has always been an eyesore, and the other will be fun to remove as an additional demonstration. I have zapped both, with less injury than occurred after the eyesore was zapped by a licensed California doc-tor. Perhaps by the end of the year I will have a full report up on youtube or tik tok.

Of migrants and measles

One of the issues with migration, is that it erodes the rational overlay between a group of people and their geography.

Without migration, to say that “something happened to people in this place” is to say that it happened to the people of that place. But when the people of another place are transported to the first place, what “happens” in the first changes, but this “happens” no longer corresponds to the people of that land, but to either the natives or the arrivals. It is immediately necessary to stop speaking and thinking about events in terms of place alone, because changes to events in place do not correspond to changes in the way-of-life of anyone in that place — only changes in their location. The overlay no longer exists. This means that the reigning contemporary approach to understanding all relevant issues — line go up!, line go down! — is almost entirely nonfunctional in the current year.

The importance of this problem was never lost on epidemiologists of earlier times. When at the turn of the 20th Century a giant fraction of new parents had been born abroad, doctors and researchers often reported cases of disease by nationality — American vs. Italian, Russian, etc. After the borders were closed in the 1920s, such distinctions were no longer made, because they were no longer useful — hence the invention of “white,” to contrast with “nonwhite,” in mid-century epidemiological literature. Relatedly, when it would be the case that certain diseases became rare or nearly eliminated at home, it became rote to report on whether new cases were imported from abroad due to travel. It meant something different, and no longer gave the same answer to the question that epidemiology asks of the data: What are the people here getting sick with?

Now America’s borders have been reopened, but such native / immigrant distinctions are something of a taboo. Pointing out that migrants change the character of the West in any form whatsoever is what we might term “potential misinformation,” which is to say a fact that will lead the native-born public to reach realistic, but undesirable conclusions.

Thus “the US” has been experiencing a dramatic surge in measles this year, which is to say several dozen cases. But is this due to another failure of Americans to sufficiently adhere to public health propaganda, or simply the result of importing unvaccinated children from parts of the world where wild measles is still common? This week, Newsnation reports that despite doctors claiming it is the former, it is at least to some extent actually the latter. This doesn’t stop Newsnation from credulously reporting the doctors’ claims as facts (because after all, barely anyone understands that claims are not facts anymore).

This would seem to be in contrast to the 11 cases reported earlier from Florida; given that DeSantis responded to the news in Chicago by pointing out that migrants were involved, but did not say the same of his own state’s cases. This leaves about 50 cases in other states (on Thursday, the CDC updated the total case count to 97); are these migrants or not, who knows. This week’s news in Chicago is the first clear report on the question, as far as I am aware.

Several states with high vaccination rates have reported cases this year:

Not accounting for differences in population and age, we can compare “team performance” for the three categories used by the CDC above. Including the three separately reported cities:

Less than 90% with cases: 30.8%

90-94.9% with cases: 36%

95+% with cases: 35.7%

(If my counting is correct: 4+, 9- dark orange, 9+, 16- light orange, 5+, 9- blue.)

The undervaccinated states include Hawaii and Alaska; in other words they are not all exposed to the open border. Perhaps this is relevant to that “team’s” higher performance.

The herd immunity efficacy illusion

Perhaps the cases in the highly vaccinated states are among migrants, or perhaps not.

Ultimately, measles tends to thrive in pockets of low immunity, which is to say a group of non-immune individuals who are in frequent enough contact to sustain transmission of the virus. What matters ultimately is not the percentage of individuals in a whole population that are not immune, but whether some number of those that are not immune are in a network of contact with each other.1

This is why “herd immunity” is not a useful term when it comes to vaccination, as such pockets of interconnected individuals can always exist even at extraordinarily high immunity rates. One must keep the virus away from them.

On the other hand, if the pocket of “susceptibles,” to use the language of the epidemiologist, is isolated and immunity is kept at a high level in the rest of the population — by constantly vaccinating the newly-born, who otherwise are themselves the main pocket of susceptibles that keeps the virus alive — measles will never find the pocket. Only if measles can constantly pass from one such source of fuel to another will it survive in the wild.

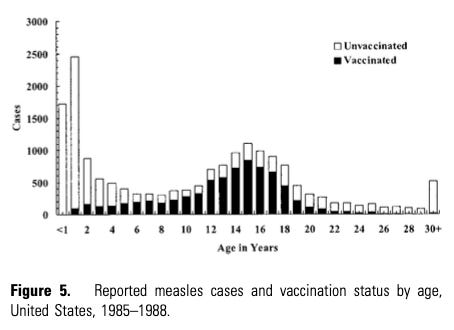

The paradox of measles vaccination is that, over the long term, it turns the entirety of society into such a pocket, as multiple generations age out of childhood without the complete immunity that is conferred by natural infection. Thus, two problems interacted to drive the resurgence in measles in the late 1980s: Inner-city preschool children were not being vaccinated, and one-time vaccinated children and young adults were still capable of sustaining outbreaks in schools and colleges. In response, the current regime of insisting on universal vaccination at 12 months and revaccination before school was instituted.

The effect of eradication is thus that the number of pockets of susceptible people — vaccinated children and adults who will get measles if exposed, or “vaccinated susceptibles” — continually expands until a point of saturation for the population as a whole. Doubling the vaccine dosage reduces the percent of vaccinated who are susceptible, but this can only make the formation of a pocket more difficult, lowering the saturation point but not eliminating the creation of pockets outright. (For comparison, “people going out and seeing each other less” effects the same change in the number of pockets.)

Preventing the spread of measles in a vaccinated population thus always requires keeping the virus away. This, I suspect, is also why the modern backlash against vaccination, reflected in the prevalence of dark orange states in the map above, has not resulted in a return to even 1980s level measles outbreaks: Most of the protection after 1993 has been a result of increased vaccination abroad, thus keeping the virus away. Whereas, a pocket of unvaccinated children is not different from a pocket of vaccinated susceptibles except in the sense that it is easier to know when the former exists.

In the current year’s tally (at the CDC page linked above), 6-ish% of cases with known vaccination status are double-vaccinated (status is only known for 3/4 of cases). Since 48% of cases are aged 5 and older, this might correspond to something like 12% of cases in that group.

16% are one-time-vaccinated, but many of these might be from arrivals at the Chicago migrant shelter. In response to the outbreak, the Chicago Department of Public Health has switched from the default CDC schedule to giving a second MMR vaccine 28 days after the first.

The Chicago Department of Public Health announced that people who were vaccinated at the shelter would receive the second dose of the measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine 28 days after their first shot.

Typically, children are eligible to receive the MMR vaccine at 12 months of age and then a second dose between the ages of 4 and 6 years, Chicago health officials said. However, the second dose of the vaccine can be received as soon as 28 days after the first was administered.

Health officials say that the policy change will prevent the spread of the virus in the facility. The expedited second dose will provide the best protection for preschool children until their immunity to measles is fully developed, the health department said.

The new policy is expected to affect about 50 children at the shelter, where more than 900 people were vaccinated in just a matter of days after the first confirmed case was reported earlier this month. Another 700 shelter residents were found to be immune from the virus after previously being vaccinated or having exposure to measles.

So, this still leaves us with a very poor idea of whether the current years’ cases have had much, if any of an impact on native-born vaccinated. Vaccine breakthrough cases do not yet appear nearly as frequent as during the resurgence in the 1980s.

Measles is not a big emergency

Notably, vaccination seemed to perform better in the 1980s in England. In a 21-year assessment of the 1964 Medical Research Council vaccine trial:2

No cases occurred after contact in the last seven years, although opportunities for contact evidently increased. This is in contrast with a report from the United States where, in an outbreak of measles in a college, the incidence among vaccinated students increased with the time elapsed since vaccination

In other words, trial subjects who received only one vaccine were well-protected from direct contact many years later, at the same time as previously vaccinated young adults in the US were frequently being infected.

What was the source of this protection?

The fact that in the 1980s, measles was still endemic in the United Kingdom, because a third of kids were not vaccinated.

It must be remembered that, unlike in the United States where measles is now a noteworthy event, measles in England and Wales remains endemic, with around 90,000 cases notified a year. There is therefore ample opportunity for antibodies induced by vaccine to be boosted […]

It is reassuring that after 21 years immunity induced by the vaccine seems to survive the increasing challenge of close contact with measles in young children [experienced when the vaccinated become parents], because unless acceptance of the vaccine in the United Kingdom increases appreciably from its current level of 60-70% this challenge is likely to continue.

This is the final twist in the measles vaccine paradox: The vaccine works better if fewer kids are made to take it; exposure to natural, endemic measles “tempers the steel” of vaccine-induced immunity. Whereas, once nearly all kids are made to take it, both the unvaccinated and vaccinated are saddled with the looming risk of being infected in late childhood or adulthood.

This paradox is possibly the root cause of the absolutely deranged reaction of health authorities to noncompliance with the American MMR schedule. They want to fight nature, but it doesn’t work.3

We are thus treated every year to apocalyptic histrionics in the media regarding a childhood illness that is so benign that in 1980s England, many parents still didn’t give any thought to preventing it. (In 1980 itself, vaccination rates for the UK were around 50%.)

The return of measles is not an emergency.

In the 1964 MRC trial, 2 of 16,239 unvaccinated children died in the first few months, and no deaths were reported afterward (almost half were vaccinated soon after, but the remaining half still experienced zero deaths).

In 1962, before introduction of the vaccine, a gaggle of CDC luminaries estimated a case fatality rate of 1 in 10,000 after age 1 in the US. Their justification for pursuing elimination anyway was “muh boredom”:4

To those who ask me, “Why do you wish to eradicate measles?,” I reply with the same answer that Hillary used when asked why he wished to climb Mt. Everest. He said, “Because it is there.”

They precede this flippant justification for dividing society forever into camps of compliers and independents by explaining that what is important in the measles question is not how it affects children, but the handful of adults who want to manage it in order to feel important:

Thus, in the United States measles is a disease whose importance is not to be measured by total days disability or number of deaths, but rather by human values and by the fact that tools are becoming available which promise effective control and early eradication.

But even on these counts, the current measles control regime is a funhouse-mirror abomination of the original vision — control is not “effective,” and eradication has yet to be delivered after a half-century, which is not “early.” Endless double-vaccination of all children for a disease orders less lethal than accidents is not even what the founders of measles eradication signed up for.

Measles carries a risk of complications. So does regular life. In numerical terms, which is to say in terms of luck, a kid who is infected with measles is not meaningfully more or less likely to die or become disabled than a kid who never is infected. It still happens at some rate to the latter kind of kid.

The measles vaccine replaced a natural illness, one humans had lived with forever, and which ceased to cause many deaths when kids were no longer as crowded at home, with an unnatural illness of the mind — one in which “sometimes kids get sick” is treated year after year as an emergency rather than the way life is.

If you derived value from this post, please drop a few coins in your fact-barista’s tip jar.

See Fox, JP. (1983.) “Herd Immunity and Measles.” Rev Infect Dis. 1983 May-Jun;5(3):463-6. doi: 10.1093/clinids/5.3.463.

Miller, C. “Live measles vaccine: a 21 year follow up.” Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1987 Jul 4; 295(6589): 22–24.

Except for when the goal is literally to “fight nature,” e.g. bug spray, antibiotics, fake sugar.

Langmuir, AD. Henderson, DA. Serfling, RE. Sherman, IL. (1962.) “The Importance of Measles as a Health Problem.” Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1962 Feb; 52(Suppl 2): 1–4.

The important question for me is: When a susceptible vaccinated person gets measles (whether the wild or vaccine strain), can they overcome the original miseducation of their immune system from the childhood shots, to develop true lifetime immunity after real measles infection?

As someone old enough to remember when every kid got the measles in the 50s and 60s, as my siblings and I did, I really appreciate what you wrote about the measles vaccine. You almost never see statistics about how many kids actually die of measles, which provides valuable context.

Forcing a vaccine on everybody which wanes as they get older so that they contract measles as adults, which I've always heard is worse than getting it as a kid, just sounds stupid.