OAS Lit Review / Timeline Pt. 2

The lifetime of a scientific myth: Fraud in the early days, confusion in modern times.

Current version: 1.01

(Studies from 1953 - 2014 are live. Studies from 2015 to present to be added in update.)

Continued from Part 1, which reviews the story of flu research leading up to 1947. The fundamentals of flu research, including the history behind the three early H1N1 strains (“Swine,” “PR8,” and “FM1”), is covered there.

“OAS” Is Not Well-Observed

The phrase we are discussing today — “Original Antigenic Sin” — was coined and defined between 1953 and 1960, with the ostensible, formal thesis issued on the last of those years. Said thesis, Francis’s “Doctrine,” is so coy that modern readers whether credulous or skeptical can’t help but imagine the author is trying to convey hidden meanings.

I have argued that this misunderstanding was in fact intended by Francis.2 But not only does the text of his “Doctrine” fail to disclose anything via coded messages, the contemporary application in follow-up research by Francis's disciples implies no “sin” — no transgression; no offense; no curse; no limitation; no detriment. From the conduct of those who went on to spread his good word to the masses, we can assign a meaning to the original term that is, well, not sinful.

OAS: “Originalist” definition / claim

Antibodies to flu strains prevalent in childhood are observed to be highest later on in life.

All antibodies to new strains cross-react with old strains; not vice versa.

That’s it. “Can’t make antibodies to new strains” is not part of the original definition of OAS. “Flaw” is not part. “Limitation” is not part.

And yet, the modern reader can’t help but imagine that those things are part.

Because the text of “Doctrine” — and (naturally) the phrase itself — so often lead readers to imagine there is some detriment at work, much of the research on OAS centers on the question of flu vaccine inefficacy. And, in fact, there may be mechanisms by which preexisting antibodies diminish the ability of injections with flu antigens to alarm the immune system, akin to a cried-wolf, “antigenic interference” phenomenon: But this would not be “OAS,” as it typically concerns previous years’ strains rather than childhood strains.

Again, we could imagine this “misapprehension” is intended by the author. It doesn’t matter.

And so, this second error further sabotages “OAS” research:

Almost none of the modern research takes childhood strains into consideration. They therefore cannot substantiate OAS. However, they still claim to be doing so, whether to lend their findings an imprint of historic precedence or simply to attract peer interest.

In other words, a crying-wolf phenomenon in flu vaccination — “antigenic interference” — has been mis-assigned the term “OAS” to attract the equivalent of “hits” in the science literature world.

Lastly, it is the case in both antique and contemporary studies of “OAS” that:

Neither of the original 2 claims is actually observed consistently. This includes in the studies cited in “Doctrine,” which are flatly misrepresented in the text.

This leads to a third category of error; as modern studies which misapprehend the definition of “OAS” tend to take the underlying mechanism for granted, to such a degree that no attempt is made to compare new antibody responses to a non-“sinned” control group. To substantiate the claim that “prior immunity limits new responses,” you must measure against a control group with no prior immunity. In practice this almost never happens; even in animal studies (but mostly in human studies).

For these reasons, the claim that “OAS is a well-observed limitation in human immunity” is the unwitting punchline in a modern scientific comedy of errors.

Imagine it being uttered after 60 minutes of footage of the Three Stooges dropping sandwiches into beakers and splashing boiling water on themselves. The speaker of the claim: An aloof and probably over-paid “serious intellectual” who needs to spend more (any?) time reading beyond the abstract.

Since “OAS” means different things to the many different authors who have “observed” it, it is impossible to offer a coherent literature review of OAS, the topic. At best, I can review different flu immunity studies that have invoked the phrase, and attempt to qualify their findings according to 3 different rubrics:

Were childhood antibodies demonstrated to be higher?

Was “imprinting” demonstrated: Did antibodies elicited by new strains cross-react or stem from existing B Cells induced by previous strains?

Was a detriment demonstrated: Were antibody levels to new strains compared to a non-“sinned” control group?

This will firewall the three main claims of OAS (one of which does not belong in the original definition, but is now part of the modern meaning) so that affirmation of any one is not mistaken for affirmation of an overarching concept. Of course, in a world where “OAS” was “well-observed,” there would be no divergence between which studies address which aspects.

We do not live in that world.

We do live in the world, however, where item 2, “imprinting,” has shown somewhat consistent validation. This, it should be noted, is despite Francis’s own results falsifying any “doctrine” to the phenomenon.3 Imprinting is something that happens sometimes.

“Imprinting”:

A non-doctrinaire (as in, non-universal) phenomenon in which B-Cell pools to originally-encountered flu strains remodel themselves upon encounter to new strains, so that all antibodies neutralizing the new strain are cross-reactive to the old strain. Imagine a basketball team that is able to swap players from the back-bench whenever the opposition changes tactics: That is (often) the B-Cell pool to original infection with flu subtypes, and perhaps with original exposure to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein.

This may be adequately measured by vintage virus absorption assays or modern B Cell clonal analysis.

Rather than demonstrating that the immune system cannot “learn new tricks,” it demonstrates that B Cell memory pools are plastic, and thus capable of performing the function of novel immune responses.

“Imprinting” can thus be considered another (somewhat overly moralistic) term for “immune plasticity.”

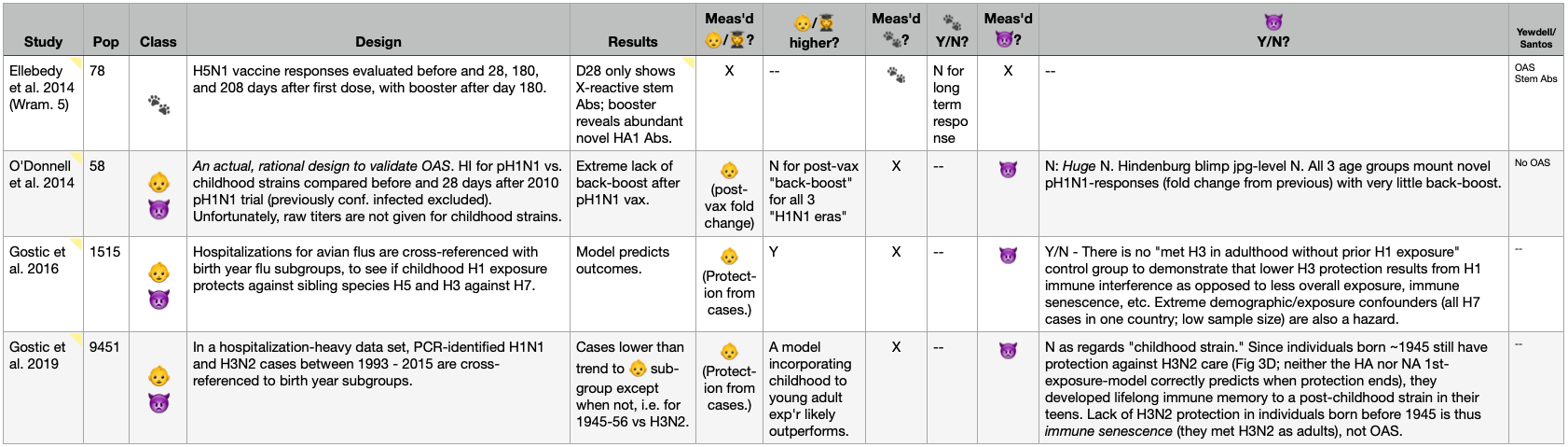

OAS, Reviewed: The Table.

Key

For those who scrolled ahead, the table below evaluates studies based on whether they provide evidence for 3 different claims which fall under the modern umbrella of the term OAS. Because different authors (mis-) understand OAS differently, few studies address all three; and perhaps none in a manner akin to synthesizing all three into a true biological dynamic.

👶/👩🎓: Childhood/1st Antibodies - These studies take the “original” part of the term seriously, by evaluating results in light of the age of subjects, and which strains would have been their first exposure to flu overall or to a given subtype. As can be seen, this is basically dispensed with in the modern “OAS revival.”

🐾: Imprinting - These studies adjudicate whether antibody or B Cell responses to variant (post-👶/👩🎓) strains are simply repurposed 👶/👩🎓 responses. In short, if no antibodies or B Cells for the variant can be found that don’t also cross-react with the 👶/👩🎓 strain, then 👶/👩🎓 has imprinted the immune response. Yes, it can be remodeled to new variants - but it’s still the “old” response. This is regardless of whether variant antibodies are “higher” than 👶/👩🎓 antibodies, and regardless of any impact on immunity or infection outcomes. In other words, imprinting is separate from detriment; it might be neutral, or beneficial, or detrimental — that must be shown separately.

👿: Detriment - These studies examine (whether intentionally or not) whether imprinting impairs immune response. The user should note that I am not generous with the grading here. For example, if imprinted subjects have higher or higher-avidity anti-variant antibodies than non-imprinted controls, then Detriment = N. It doesn’t matter if those antibodies are still lower than the 👶/👩🎓 antibodies; they are higher than a naive response, implying benefit from imprinting. As a simple analogy, Michael Jordan was still better than most humans at baseball, with relatively little baseball-specific training: Training at basketball therefore did not make Jordan worse at baseball in per-baseball-training-units.

Yewdell/Santos - This column prints the rating assigned in the 2021 review around which the table is partially organized.4

Early Era: A Foundation in Fraud

On Page 1, we see the “first generation” of studies directly or indirectly addressing “OAS.” Blue studies are canonical — as in typically cited as the bedrock proof for OAS — even if erroneously, as in the case of Hoskins, et al.

And so, in my admittedly ungenerous scoring, none of the claims in the OAS umbrella besides “imprinting” receive more than the occasional confirmation, and even that is often not affirmed.

Most notably, we can see that three of the first four studies, all from Francis’s school, frequently refute the core claims of OAS: That childhood antibodies are higher, or that “imprinting” is destiny. These inconvenient findings are simply misrepresented or ignored in “Doctrine," but Francis’s disciples are no less guilty on this front.

Take, for example, Davenport & Hennessy’s 1957 report, “Predetermination By Infection And By Vaccination Of Antibody Response To Influenza Virus Vaccines.”5 In the Summary, they write:

In either case [after monovalent or polyvalent vaccines], predominant antibody response was of a "booster" type, directed against the major antigens of strains of original infection.

However, the actual results for the monovalent vaccines — where just one strain is injected — directly contradict this claim in 3 of 6 cases. Naturally, Davenport and Hennessy present those results in as obscure a format as possible, forcing the reader to perform brain-breaking coordinate matching to compare “back-boost” responses to vaccine responses.

We may think of this as a sort of soft fraud — Davenport and Hennessy do not fake their results; they merely render them impossible to parse, and then ignore them.

This reinforces the mischaracterization offered for the same experiments the year before, when results for "imprinting" based on serum-absorption were reported in the Summary as:6

Absorptions of sera from groups of persons, both normal and after vaccination, resulted in complete removal of antibody to all strains of influenza virus within a type when a strain of antigenic configuration similar to that presumed to be the strain of first experience was employed.

Again, the presentation is deliberately obtuse. The essential claim being made is that after vaccination with a non-childhood strain, no antibodies resulted that could not be removed by dunking the childhood strain into the sera of different age groups. If adults were given an “FM1” (1947-study present) vaccine, for example, the sentence above asserts that “SW” (1918-1932) virus would absorb all “FM1” antibodies.

And then, of course, this fraud entered “OAS canon” in 1960 when Francis repeated it in “Doctrine.” Speaking not of any novel results but the same exact experiments in the three age groups above, he claimed:

[S]wine virus removed all antibody from the serum of the middle aged.7

For this reason, OAS as a scientific concept has from the start been built on an edifice of deception, and of denying observed reality to suit a pre-determined conclusion.

And so, OAS as any kind of “doctrine” in 1960 was nothing more than mere scientific fraud; and it remains to be seen if it is, to this day, anything other than that.

Early Era Twilight: Antigenic Interference, Vaccine Failure, And Natural Immunity

Before they ventured into misrepresenting their own results in summaries, Davenport and Hennessy published results from a valuable experiment conducted in 1953. These results are instructive when compared with the “vaccine futility” studies by Hoskins, et al. in 1979 and Masurel, et al. in 1981.8

For the latter studies, children given sequential vaccination to in-subgroup strains cease to be protected or generate new antibodies. In both cases, the subgroup in question is not actually the children’s “childhood” strain, as they would have been imprinted to H2N2 in one case (and vaccinated for H3N2) and H3N2 in the other (and vaccinated for H1N1). Extending “OAS” into non-childhood subgroups is not irrational, but it creates conflicts with the original usage and with subsequent work by modern authors. We can set that aside for now.

Both of these studies — one measuring vaccine efficacy with infection outcomes, and the other antibody response — demonstrate that “OAS” as it is commonly used does appear to have a limited relevance with regard to vaccination: As I have described it before, vaccination is a “trick” that can be pulled on the immune system only once.

In Hoskins, et al., H3N2 vaccines are effective (lead to fewer infections) the first time around, even though the infections in question are in all cases with a new variant vs. the vaccine strain (note that some subjects in both arms probably already had natural immunity to H3N2 to begin with; but for those that didn’t, the first vaccination was protective). Afterward, injection with a later variant vaccine does not replicate the protection. The “one shot” has apparently been used up.

Importantly, this isn’t a story about “adapting to variant vaccines,” though modern writers might want to see it as such. It does not offer support for tropes that “update failure” is a “major reason” modern vaccines seem not to work — and any writer who says it does, hasn’t read the study. In fact the vaccines wind up being out-of-date in two of three waves anyway. The “England” virus is preceded by the “Hong Kong” vaccine; the “Port Chalmers” by a like vaccine; and the Victoria with “Port Chalmers” again — and in all cases the out of date vaccines perform well for the first-timers. Additionally, Hoskins et al. are not even reporting antibody response. On this front, however, the next study provides a classic “variant update failure” demonstration.

In Masurel, et al., vaccines to the returned 1950-like strain of H1N1 (A/USSR/77) are only effective if children haven’t already been given a 1918-like swine H1N1 vaccine (A/NJ/76). The A/NJ/76 back-boost, in those that were “sinned” with the swine vaccine, is substantial, especially after a second dose of A/USSR/77. The range of post-second-Russia-dose swine geometric mean titers in the “sinned” groups (243 - 621) is higher than the range of Russia titers in the non-“sinned” groups (198 - 266). This seems to account for why the “sinned” groups are only producing Russia titers in the 59-133 range; and even those numbers are exaggerated by a few high responders. Most responses are just low.

Again, the “one shot” to train these immune systems via artificial injection has been used up; these kids will probably get just as much symptomatic infection with H1N1 as if they had never been vaccinated at all.

But, to return to Hoskins, et al., it is at this point that their “sin” will likely be erased. Whether schoolboys were recorded as infected without any vaccine or after double-vaccination leading to vaccine failure, their infections produced durable immunity to H3N2.

[In the 1974 wave] There were no cases in boys known to have been infected in the [1972] outbreak. […]

[In the 1976 wave] No boy who had a confirmed attack in the [1974] outbreak was affected [including all those who had experienced vaccine failure leading to infection in 1974] and only 1 who was affected in the [1972] outbreak.

For comparison, the attack rate for the new class of vaccine-failures in 1976 was a whopping 59%, higher than the unvaccinated — true negative efficacy, likely due to fewer borderline infections in the waves before leading to less natural immunity, i.e. immune debt. But the prior classes of vaccine-failures from 1972 and 1974 were now returning perfect scores via, once again, natural immunity. The problem had solved itself; the training wheels had been removed.

The immune system was thus never truly “stuck” in the antibody response to the original injection. The effect of vaccination was therefor not detriment, but futility: It was merely putting off the inevitable infection that would lead to durable immunity to the 1968-emergent H3N2 subtype. Hoskins, et al. thus do not propose more endless research into “solving” the problem of antigenic interference, but rethinking flu vaccination altogether (emphasis added):

When a new subtype appears it should be possible to reduce the first outbreak to manageable proportions, but subsequent outbreaks may not be modified to a useful extent.

These observations on three outbreaks of influenza A in a school suggest that annual revaccination with inactivated influenza-A vaccine confers no long-term advantage. The practice of offering annual revaccination to adults seems open to question.

This brings us, at last, to Davenport and Hennessy’s findings in the 1953 trial. Here, unlike Masurel, they find that response to a new H1N1 strain (“FM1”) vaccine exceeds the “back-boost” of the childhood strain (“PR8”), in young Air Force recruits. This despite the fact that FM1 and PR8 were only one major antigenic shift apart, while Masurel’s Swine and Russia strains spanned the known history of H1N1.

What explains the difference? Most likely:

Prior natural exposure to FM1-like strains between 1947-1953, leading to new B Cell memory pools or remodeling of the existing pool.

Crucially, the titers to the representative 1947 strain were already near-equal with the imprinting PR8 strain to begin with, a result that would not have been found in this age group in 1947:

Additional support for presuming pre-existing natural immunity is in the short time frame (2 weeks) between vaccination and the draw; the FM1 response (measured by Rhodes) is not novel, but recall.

This hardly reverses the conclusion that adult flu vaccination should be questioned: It seems that most young adults in 1953 already had immunity to the newer model, based on exposure to FM1 after 1947. What it does show, is that they had this immunity despite FM1 not being their “imprinting” strain. Left to their own wiles, the immune systems of these then-teenagers had cast aside the “sin” of their childhood exposure to PR8.

Their immune response was no longer oriented to the childhood strain.

Prescribing the remedy for repeat-vaccine failure, however, is impossible until the lack of a similar detriment in natural, infection-based immunity in the young is acknowledged.

Biologists, at last, must leverage common sense to overcome a simple category error. Just because initial vaccination can replicate the immune response of infection, it does not follow that vaccination and infection or even asymptomatic viral encounter are actually the same.

Thus, limitations with repeat vaccination are actual limitations with vaccination, not within the immune system.

In a context of natural encounter with variant viruses, the evidence for immune plasticity (remodeling of imprinted B Cell pools) and novel immune response overflows. It only awaits acknowledgement.

2009 “Pandemic” Era: The White Whale of Emory

Page 2 leads us into a constellation of studies highlighted by Yewdell and Santos in Table 2 of their 2021 review, “Original Antigenic Sin: How Original? How Sinful?”9

This modern review seemed like a rational template for my own appraisal; in retrospect I have come to wonder whether Yewdell, who was partially involved in the Wrammert series, is only carpetbagging on the “OAS brand” to boost the alleged findings of this series. Oddly, however, the text of the review gives little mention to the findings aggressively featured in their table.

The Wrammert series consists of 5 studies involving vaccination or infection with the overhyped 2009 “swine” flu (pH1N1 in the table). The overall motif of the series is a speculative theory that repeat experience with influenza drives the immune system to shift attention from the ever-changing head region (HA1) of the flu spike glycoprotein toward conserved elements of the stem. The problem is that Wrammert and the Gang keep using early serum draws, over and over, to support their results.

In fact, the two cornerstone papers in the series appear to use draws from around day 10 after natural infection with the Overhyped 2009 Swine Flu.10 In the first, activated, flu-specific B Cells in 9 donors are cloned and analysed, with the finding that most are highly-matured, implying that they are recalled responses to prior flu encounters. These are found to focus on the stem, as opposed to the typical novel immune response's focus on the head of the spike (HA) protein. Yewdell (a co-author on this paper) and Santos thus score this one as "OAS stem abs," even though some of the B Cells are already specific to the Overhyped 2009 Swine Flu.

It should go without saying that if there is a little “new” at Day 10, chances are good of there being even more “new” later. But no follow-up bloodwork is presented in the 2011 paper. Observing that these active, cross-reactive Day 10 B Cells are stem-focused, Wrammert and the Gang embark on a quest to turn these findings into an edifice for a stem-based, universal flu vaccine.

The logic of Wrammert’s theory might seem sound: If the receptor binding domain is radically remodeled by antigenic shift, wouldn’t the immune system “wise up” and target the most conserved regions of the spike protein? Well, no — not unless it has given up on novel immune responses completely. As prior antibodies against the head region bind poorly, there should be an immune response to the head region of antigenic shift variants (or alternate subtypes, or divergent subtype models like the Overhyped 2009 Swine Flu, etc.). This is the prediction demanded by the current understanding of how new B Cell responses are generated:

So, it would behoove any researcher pursuing a theory of “immune wisdom” which overrides new B Cell immune responses to wait long enough for new B Cell responses to arrive, before concluding that they aren’t doing so.

The next year’s installment demonstrates expansion of stem-targeting recall B Cells again, after a pH1N1 subunit vaccine.11 Here, 28 days is the time from vaccination. Again, I would argue that this isn’t long enough. A follow-up study recycles the donor pool of the 2011 paper, though my analysis of the results suggest that rather than day 10 draws, a later set of draws was used.12 Here, Yewdell and Santos slap on the coveted, unmodified "OAS" rating, due to the fact that patients born between 1983 and 1996 mount an immune response that depends on a pH1N1 epitope (K133) that happened to reappear in circulating human H1N1s in those years, before mutating again afterward.

Both our reviewers and the original authors ignore the finding that the youngest patients (from a different study's sample set, taken 28 days after infection), who do not show immunity to contemporary H1N1 strains, also mount a response highly centered on the same epitope in pH1N1.13 Thus, the “OAS” response exactly resembles a naive response. And in all cases for the adults, whether their early response centers on K133 or not, blood draws taken later might reveal a richer story.

At last, the final paper in the series completely validates my argument that even 28 days is not long enough.14 Wrammert and the Gang throw a H5-headed vaccine at their study subjects this time, finding only an expansion of stem-binding antibodies in most donors at day 28.

They return 6 months after the first injection to administer a booster. Suddenly, all but one subject has abundant antibody responses against the novel H5 head; the “boost” injection leads to high expansion of this response; and expansion in the conserved stem region is negligible:

Despite a lifetime of exposure to the conserved stem region, almost all subjects generated a from-scratch immune response to the radically novel H5 head. They were not “sinned” from their childhood H1N1 encounters; they were as kids again, discovering flu for the first time.

Wrammert and the Gangs’s tower of ladders, built on repeated premature blood draws, had collapsed. They had tried to sell the immune system a “no bells and whistles,” stem-centric version of flu immunity; the immune system rolled off with the shiniest ride on the rack.

Of course, they don’t concede that the booster results negate the day 28 results in their own Discussion, proudly touting:

immunization with an inactivated H5N1 vaccine considerably improved the cross-reactive anti-HA stem responses [until we checked back later, and it turned out not to have done that at all]

Yewdell and Santos merely conclude, “OAS stem abs.” No bar is too low for that label to jump over, apparently.

Whether the Wrammert series is included in their review in order to appropriate “OAS” to highlight a “Stem Antibodies White Whale” or not, it is a fitting reincarnation of Francis’s initial obsession. In both quests, near-fraudulent manipulation and misrepresentation of results sustains a far-fetched dream of being the one to crack a universal flu vaccine; and “Original Antigenic Sin” is just the tagline to bolster peer interest in the mariner’s hopeless hunt.

If you derived value from this post, please drop a few coins in your fact-barista’s tip jar.

Changelog:

August 30, 2022 - v 0.1:

“Beta” version published.

August 31, 2022 - v 0.2:

Added Masurel, et al. (1981.) to table. As this represents a classic “OAS as detriment” demonstration in the vaccine context (in humans), I am surprised it is not more often cited.

Added section, “Antigenic Interference, Vaccine Failure, And Natural Immunity.”

September 2, 2022: v 1.0:

Added page 2 of table.

Added section, “The White Whale of Emory.”

Added Nobel, et al. (1977.) to table, the absence of which was an oversight.

See “The Mess Francis Made.”

See “Flu: The Lost Years.”

Yewdell, JW. Santos, J. (2021.) “Original Antigenic Sin: How Original? How Sinful?” Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2021 May 3;11(5):a038786.

Davenport, FM. Hennessy, AV. (1957.) “Predetermination By Infection And By Vaccination Of Antibody Response To Influenza Virus Vaccines.” J Exp Med. 1957 Nov 30; 106(6): 835–850.

Jensen, KE. Davenport, FM. Hennessy, AV. Francis, T Jr. (1956.) “Characterization Of Influenza Antibodies By Serum Absorption.” J Exp Med. 1956 Aug 1; 104(2): 199–209.

Francis, T Jr. (1960.) “On the Doctrine of Original Antigenic Sin.” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. Vol. 104, No. 6 (Dec. 15, 1960), pp. 572-578.

Davenport, FM. Hennessy, AV. (1953.) “Comparative Incidence of Influenza A-Prime in 1953 in Completely Vaccinated and Unvaccinated Military Groups.” Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1955 Sep; 45(9): 1138–1146.

Masurel, et al. (1981.) “Antibody response to immunization with influenza A/USSR/77 (H1N1) virus in young individuals primed or unprimed for A/New Jersey/76 (H1N1) virus.” J Hyg (Lond). 1981 Oct; 87(2): 201–209.

Hoskins, et al. (1979.) “Assessment Of Inactivated Influenza-A Vaccine After Three Outbreaks Of Influenza A At Christ's Hospital.” Lancet. 1979 Jan 6;1(8106):33-5.

Wrammert, J. et al. (2011.) “Broadly cross-reactive antibodies dominate the human B cell response against 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza virus infection.” J Exp Med. 2011 Jan 17;208(1):181-93.

Li, GM. et al. (2013.) “Immune history shapes specificity of pandemic H1N1 influenza antibody responses.” J Exp Med . 2013 Jul 29;210(8):1493-500.

Li, GM. et al. “Pandemic H1N1 influenza vaccine induces a recall response in humans that favors broadly cross-reactive memory B cells.” Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012 Jun 5;109(23):9047-52.

(Li, GM. et al. 2013.) In Table S3, donors are reported to have higher HI than in Table 2 of the 2011 paper. The text of the 2013 paper, however, merely refers to the 2011 paper and doesn’t provide any additional clarification on symptom-to-sampling times. For this reason, I rate the results as “questionable” in my table.

(Li, GM. et al. 2013.) Table S3; subjects 25, 30, 46-54. H1N1-naive children (<10 titers to contemporary H1N1) also produce sera that is sensitive to a mutation to the “OAS” epitope, reflecting that this epitope is the natural target of a naive immune response. Further, the study design does not rule out a similar response in patients previously exposed to H1N1 with an alternate residue in the K133 position, since their antibodies against the alternate residue would simply mask any “drop” in novel anti-K133 antibody binding. However, it is unlikely that novel anti-K133 antibodies would be prevalent in such early draws.

Ellebedy, et al. (2014.) “Induction of broadly cross-reactive antibody responses to the influenza HA stem region following H5N1 vaccination in humans.” Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014 Sep 9; 111(36): 13133–13138.

I'm not all the way through this yet, it's going to take a few sessions. But thanks. It's helping me understand some of the terms that get thrown around. Like "imprinting". From what you describe as the process that's a poor term for it. Confusing. But I'm a physicist and we get irritated by unclear language.

I really appreciate knowing this. I would have never questioned original antigenic sin until you started talking about it.