The BA.5 Summer Survey Study

Triple-dosed Covid vaccine recipients across US self-report highest infection rates between June 16 and July 2. And: Unrelated virus truther spam hits the comments.

A phone-based survey of US adults finds higher rates of reported SARS-CoV-2 infection among the triple-Covid-vaccinated during the BA.5 wave, and no apparent benefit from injection for long-term post-infection symptoms (“Long Covid”).

The study:1

As the metrics show, it has made a bit of a splash on social media, primarily thanks to Eric Topol highlighting (incorrectly) the findings for “Long Covid rates from BA.5.”

In fact, this phone-survey-based paper shows infection rates around the time of BA.5, and ongoing reported long-term symptoms from infections before BA.5. Get it together, Topol.

The top-line results:

Infection:

(Definition for “infection” provided in Set Up section, below. All results subject to extreme Limitations discussed below.)

Survey-reported infection rates, June 15 to July 2, US:

“In last two weeks”:

Survey conducted between June 30 - July 2. Reported infections reflect last two weeks for each participant.

All (3,042 replies): 17.3%

“Boosted” (1,610 replies): 23.2%*

“Fully vaccinated but not boosted” (476 replies): 6.9%

All vaccinated: (2,086 replies): 19.5%

Unvaccinated or partially vaccinated (957 replies): 12.6%

Between two weeks and 1 month ago:

Based on total prior infections - infections ≥ 1 month ago; these will overlap with “prior infections” below and may or may not overlap with “last two weeks” infections.

All vaccinated: (2,086 replies): (987-644) = 16.4%

Unvax’d/part’l (957 replies): (501-392) = 11.4%

Reported “Prior infection” rates (all before June 15):

All vaccinated: (2,086 replies): 47.3%

Unvax’d/part’l (957 replies): 52.4%

“Last two weeks” rates in light of reported prior infection status:

Prior reported infection vs. not may build in a bias for/against testing positive; rates for previously vs. no prior (e.g. 19.3 vs, 4.6, for unvaccinated) are thus probably not comparable.

Previously infected, vaccinated (987 replies): 31.9%

Previously infected, unvax’d/part’l (501 replies): 19.3%

No prior infection, vaccinated (1,099 replies): 8.3%

No prior infection, unvax’d/part’l (456 replies): 4.6%

(*Note that “Boosted” took recent tests at a higher rate (49.7%) than “Fully”(30.9) and Unvax’d/Part’l (35.2%). Since it is paradoxically impossible to tell whether this drives or is driven by higher case rates, I have decided not to adjust for this difference.)

“Long Covid”:

(Definition for “Long Covid” provided in Set Up section, below. All results subject to extreme Limitations discussed below.)

Survey-reported ongoing “Long Covid” rates, June 16 to July 2, US:

Reported infection ≥ 1 month ago

“Boosted” (among 448): 19.2%

“Fully” (among 196): 25.1%

All vaccinated (among 644): 21%

Unvax’d/part’l (among 392): 22.2%

Overall

“Boosted” (among all 1,610 replies): 5.3%

“Fully” (among all 476 replies): 10.3%

All vaccinated (among all 2,086 replies): 6.5%

Unvax’d/part’l (among all 957 replies): 9.1%

Too early to report Long Covid rate, prior infected

(Prior - ≥ 1 Month ago) / All Prior

All vaccinated, prior infected: (987-644)/987 / 34.8% have had an infection too early to report Long Covid for

Unvax’d/part’l, prior infected: (501-392)/501 / 21.8% have had an infection too early to report Long Covid for

Too early to report Long Covid rate, overall (est’d)

((.25 )“Last two weeks”+Prior-≥1Month) / All group; .25x is to discount for possible double-counted infections; range shows total without discount

All vaccinated: ((.25 or 1)407+987-644)/2086 = 21.3% to 40% have had an infection too early to report Long Covid for

All unvax’d/part’l: ((.25 or 1)121+501-392)/957 = 14.6% to 24% have had an infection too early to report Long Covid for

Adjusted overall Long Covid rate (est’d)

Absent future infections, assuming 20% (.2x) Long Covid rate for all pending (too early to report) infections

All vaccinated: 6.2 + .2(21.3 to 40) = 10.46% to 14.2%

All unvax’d/part’l: 9.1 + .2(14.6 to 24) = 12.06% to 13.9%

Takeaways:

“Negative efficacy” may still, even at this late date, actually be partially an artifact of lower-than-expected previous “first infection” rates.

However, it also seems to be driven by higher reinfection rates.

Covid-vaccination does not make a difference to self-reported “Long Covid” rates after infection.

And while current overall reported “Long Covid” rates are lower in the Covid-vaccinated group, this may even out or reverse after the current wave of infections, depending on how many recent infections are double-counts.

All of these observations are subject to obvious, extreme limitations due to bias, as discussed in the “Limitations” section below.

Background 1: Survey Slumming

The City University of New York has a “turn people’s money into bewildering health data” commando team, called the Institute for Implementation Science in Population Health (ISPH). It is a large crew of young, frequently modelesque investigators and staff, led by a physics BS who pivoted to public health and now makes regular media appearances when opinion on such matters (public health, not physics) is wanted.2

Upon the advent of the “Omicron era,” Nash’s ISPH took a curious pivot of its own, from boring longitudinal cohort tracking and sociological wonkery, into rapid-fire surveys. The first survey, during the BA.1 wave, targeted New York City residents by phone, text, and web. The survey series appears to be spearheaded by Saba Qasmieh, a psychology BA who pivoted to public health, toured with public health initiatives in lower income countries as a research fellow and intern, and is now mentored by Nash in pursuit of her doctorate at CUNY.

I provide all these details for flavor. It is interesting, to me at least, that this survey series stems from an organization that would presumably normally not break the mold, get mud on its shoes, etc. I was surprised when the paper turned out not to originate from some more “backwater” outpost. I also want to make everyone feel jealous for not having become a fake-science public health pencil-pusher with coworkers that look like the staff page at ISPH.

Background 2: Out Go the Lights

But didn’t we already know about negative efficacy? Well, I would say no.

At the same time as Qasmieh launched the survey series, health authorities™ around the globe pulled the switch on their case-tracking for SARS-CoV-2, with the slack in the US (where tracking, and especially recording of injection status, was never rigorous to begin with) being taken up by, primarily, Walgreens.

The Walgreens data has painted a portrait of rampant negative efficacy (though, less so at the moment), except there has never been any way to control for how many folks are showing up to be tested. In this way, it is just as flawed as any “test negative case-control” study design: For all you know, all it is really showing is how few non-infected Covid vaccine recipients show up for a test.

This would particularly seem to be the case as now, after the spring and summer, positivity rates have gone up in all groups — and they are far more level.

So, test-takers are now more selective (higher positivity rates, suggesting more test-takers have a valid reason to suspect infection) in all groups, but especially the unvaccinated, and positivity rates are now more even. This suggests that in the spring and summer, there were simply more non-selective unvaccinated test-takers (those taking tests without any plausible reason to be positive), which depressed their positivity rate.

But being suggestive of a bias is not proof of a bias, either. It doesn’t rule out actual negative efficacy. And, positivity rates are still higher in the injected, even if less dramatically so.

In this context, Qasmieh’s phone / text / web-based survey is a valuable supplement to the Walgreens signal.

Limitations

Nonetheless, there are obvious limitations and biases in phone-based surveys as well. A reviewer of the second paper in the Qasmieh series fairly rated it as “Potentially informative.”

The main claims made are not strongly justified by the methods and data, but may yield some insight.3

In particular, survey respondents will tend to be more highly-educated and affluent than the population as a whole. These, we can imagine, will also make up the majority of self-reported Covid vaccinated.

Non-highly-educated, affluent survey responders will, by definition, not actually be representatives of their groups (who usually don’t respond to surveys). They will be outliers. They will also, we can imagine, comprise the majority of self-reported unvaccinated. But we can also imagine that “Tell the survey what it wants to hear” types will fall into this group; some of them will report being injected when they haven’t been, or infected or uninfected likewise, simply because they don’t wish to rule out that the survey is secretly being conducted out of a floral delivery van two houses down the street full of Merrick Garland’s goons.

Further, as the authors acknowledge in the Discussion section, the headline value of case rates is probably an over-estimate. Recently-positive-tested may have been more likely to complete a survey concerning the virus; this bias alone could exaggerate case rates by an order of magnitude. Arguing against such a flaw, the survey found a 33.9% (reported) positive rate for (reported) recent provider-issued tests, matching the current Walgreens rates. So the bias may only extend to those who have recently tested, not the result they obtained.

Further, it is not difficult to imagine how a “positivity bias” might be specific to injection status. And there is no way to tell if this would be favorable (relative rates were actually even worse) or unfavorable (relative rates were actually better) to the injections.

Again, the key context here is that Qasmieh, et al. is another supplement to the Walgreens tracker and many other hints of negative efficacy.

The Set-Up

The first two ISPH surveys — fired off during the BA.1 and BA.2 waves — were limited to New York City residents, and featured abysmal response rates for landline contacts (1.8 and 1.3%).4 (But they also found higher reported infections in the Covid-vaccinated.)

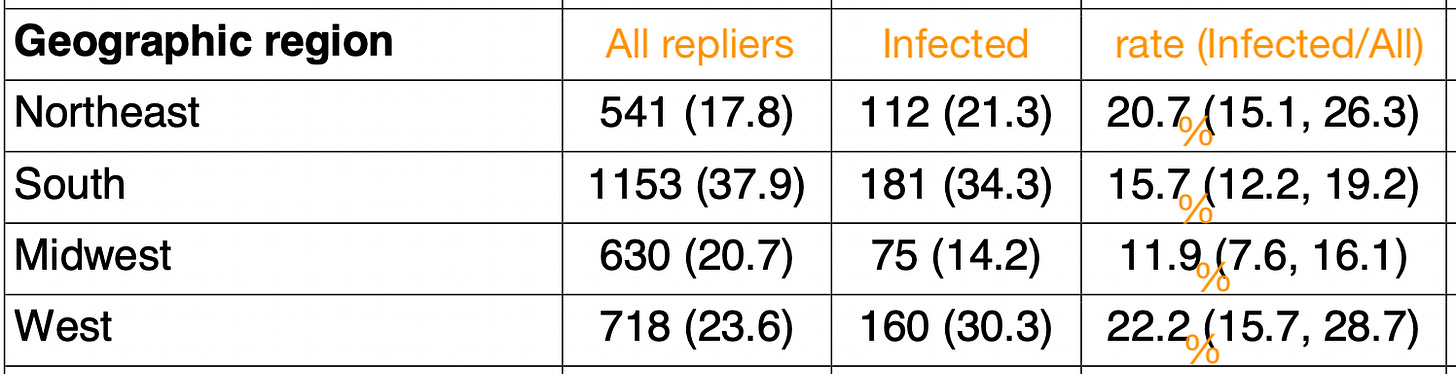

The new entry, timed to the beginning of the BA.5 wave, cast a net over the entire US and received a 6.2% completed rate for landline contacts (with .9% for text and 86.5% for web). Participants were targeted (“weighted”) in order to represent the demographics of their regions. This should diminish the educated, affluent bias somewhat, particularly given the high amount of responses from the South.

Again, this likely introduced bias, as rural, landline-answering southern and midwestern repliers may have reported the highest “unvaccinated” rates; and may have been at less risk of exposure. It is what it is.

Case definition

The survey asked:

In the past 2 weeks, have you experienced any COVID-like symptoms (e.g., 100 degrees fever or higher, chills, cough, sore throat, fatigue, headache, shortness of breath, congestion or runny nose, muscle aches, loss of smell or taste, nausea, or diarrhea)?

In the past 2 weeks, were you aware of an exposure you had to someone who had COVID-like symptoms or tested positive for COVID-19?

In the past 2 weeks, have you taken an at-home rapid test for COVID-19?

In the past 2 weeks, have you taken a rapid antigen or PCR test for COVID-19 from a healthcare or testing provider?

Respondents were classified as:

Possible case:

Reported symptomatic and exposed (79 / 527 total cases)

Probable case:

Reported positive home test only (145 / 527 total cases)

Confirmed case:

Reported positive test with provider (303 / 527 total cases)

Positivity rates are produced by counting all three types of cases together.

“Long Covid” Definition

The survey asked:

Would you describe yourself as having ‘long COVID’, that is you experienced symptoms such as fatigue, difficulty concentrating, shortness of breath more than 4 weeks after you first had COVID-19 that are not explained by something else?

For Table 3, the number of Yes’s to this question is set over a denominator determined by how many previously-infected, by injection status, selected options besides 1 in the list below:

When was the last time you had COVID?

Within the last month (if you currently have COVID, choose this option)

1-3 months ago

3-6 months ago

6-12 months ago

>12 months ago

Don’t know/not sure

“Unvaccinated” Definition

Further questions drilled into demographics, including, naturally, injection with a so-called Covid vaccine. Due to the structure of the question, anyone considering themselves “Partially vaccinated” would have been encouraged to press 2 or 3, self-classifying as what the final results term “unvaccinated.”

Have you been fully vaccinated against COVID-19? [Either 2 doses of mRNA vaccine series (Moderna or Pfizer) or a single dose of Johnson and Johnson COVID-19 vaccine]

Yes

No (go to 14)

Don’t know/not sure (go to 14)

I will only note that I have never obsessed over this designation. I actually think the partially vaccinated should be counted as unvaccinated for two weeks and then counted as “fully” vaccinated, based on every attempt I have made to parse any distinction in immune performance. Or they should be excluded. But I do not think they “hold down” the performance of the unvaccinated if they are lumped together, and the “worry window” is a myth.

Moreover, I would wager that there were likely only a handful of “partially” vaccinated in the survey population; many might have self-reported as injected based on the complexity of the question; and these are probably fewer than the numbers of respondents who misreported status to begin with.

The Results

As summarized above.

Regarding the higher rates of reported infection in the Covid-vaccinated, the authors propose that this is due to lower rates of prior infection:

Similar to prior findings using the same methodology, we estimated a higher prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection among those who were vaccinated and boosted compared with those who were fully vaccinated but not boosted and those who were unvaccinated. Since vaccines and boosters provide limited protection against infection with omicron variants compared with prior strains19, these differences are likely due to differences in SARS-CoV-2 exposures and health behaviors between the two groups. Differences could also be partly explained by the higher testing rate among vaccinated and boosted persons, which when done for screening purposes, could result in greater detection of asymptomatic infection.

The reader may see “infections were higher because they were lower” and reach for the double-speak alarm; but the math checks out in principle. If you add 5 apples to 50 and 1 to 60, the second barrel still has more apples, and the lifetime apple rate is still lower for the first. I may add an adjustment for both these considerations (previous infections and testing rates) in an update. For now I will note that testing rates in lower income and younger groups was surprisingly high. The reader could probably trawl Table 2 for themselves to come up with some interesting insights. I have prioritized making the study design and top-line results legible.

What about future triple-dosed “Long Covid” rates?

Unfortunately, the lack of a prior infection count by “fully” or “boosted” status limits showing recent and pending infection rates by status. However, since the “fully” vaccinated group reports few “last 2 weeks” infections, most of the recent / pending infections that will drive future “Long Covid” percentages to increase were among the triple-dosed.

Reported infections in last two weeks

“Boosted”: 374/1610 = 23.2%

“Fully”: 33/476 = 6.9%

Boosted / All Vaccinated case multiplier: 374/(374+33) = .92

Simulated too early to report Long Covid rate, triple-vaccinated

((.25 )“Last two weeks”+Prior-≥1Month) / All group; .25x is to discount for possible double-counted infections; range shows total without discount

“Boosted”: ((.25 or 1)374+(.92)(987-644))/1610 = 25.4% to 42.8% have had an infection too early to report Long Covid for

Simulated adjusted overall Long Covid rate

Absent future infections, assuming 20% (.2x) Long Covid rate for all pending (too early to report) infections

Boosted: 5.3 + .2(25.4 to 42.8) = 10.38% to 13.86%

This turns out not to be very different than the overall vaccinated estimates; but it is important to demonstrate that loss of the current low-Long Covid-rate status of the triple-injected would be what drives this change. The only apparent reason for that lower rate is that the triple-injected had not experienced normal rates of first infection by the beginning of the summer.

Why such low rates for double-dosed?

Lastly, it is interesting the “Fully” group reports low rates, and are also not heavily represented in the survey to begin with. This is in contrast to the patterns observed in the Walgreens dashboard.

This may be a bias toward so-called “hybrid” immunity, indicating that many winter and spring BA.1 and BA.2 infections self-sorted into this group by declining a third dose. It is only partially possible to account for this effect, as Table 3 provides the numbers for infections over 1 month prior (excluding those within the last month):

Est’d susceptibility rate, last month infections excluded

(All repliers - Previously infected ≥ 1 month ago) / All repliers

“Boosted”: (1610-448)/1610 = 72.8%

“Fully”: (476-196)/476 = 58.8%

Unvax’d/part’l: (957-392)/957 = 59%

Testing rate, last two weeks

“Boosted”: 809/1610 = 49.7%

“Fully”: 329/476 = 30.9%

Unvax’d/part’l: 620/957 = 35.2%

Positivity rate per all repliers, last two weeks

(Same as reported way up above.)

“Boosted” (1,610 replies): 23.2%

“Fully vaccinated but not boosted” (476 replies): 6.9%

Unvaccinated or partially vaccinated (957 replies): 12.6%

Adjusting for testing rates wouldn’t seem to make much difference here. The “Fully” group seem to have just as much infection-based immunity as the un-injected groups, and appears to be showing 45% efficacy against reported infection.

The answer may lie in a Simpson’s Paradox embedded within the “Fully” group. They may turn out not to be primarily recently-dosed; but that all of the recently-dosed are among the 58.8% not-previously-infected (who, in all groups, are probably biased against testing positive to begin with). So if both the “Fully” and “unvaccinated” groups only have a small group of true susceptibles (not already BA.1/2 infected, and not biased against testing positive), it could be that nearly ~100% of recently-second-dosed are in this group, so that the infection efficacy in the “players on the field” (susceptibles) carries over to the team as a whole.

Further answers, obviously, could be derived with the raw data for the survey results.

If you derived value from this post, please drop a few coins in your fact-barista’s tip jar.

Qasmieh, SA. et al. “The prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection and long COVID in US adults during the BA.5 surge, June-July 2022.” medrxiv.org

Degrees” given in https://sph.cuny.edu/about/people/faculty/denis-nash/

Lim, T. “Review 1: "The Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Uptake of COVID-19 Antiviral Treatments During the BA.2/BA.2.12.1 Surge, New York City, April-May 2022"” rapidreviewscovid19.mitpress.mit.edu

Qasmieh, SA. et al. “The prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection and other public health outcomes during the BA.2/BA.2.12.1 surge, New York City, April-May 2022.” medrxiv.org

Qasmieh, SA. et al. “Estimating the Period Prevalence of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Infection During the Omicron (BA.1) Surge in New York City (NYC), 1 January to 16 March 2022.” Clin Infect Dis. 2022 Aug 12 : ciac644.

So, perhaps, Ba.5 is a "boosted people variant"

Just want to remind, that antibody test for 'SARS-cov-2' means NOTHING, completely unspecific, unless the real symptoms actually indicate some sort of illness/cold/flu. Any old style corona virus infection with almost 90% IDENTITY of those old SARS viruses could have produced exactly one of those IgG, IGA, IgM major antibodies and their subtypes. One has to remember the just few sorts of antibodies were produced against ALL PREVIOUS DISEASES in the entire human live, until WHO/CDC changed the definitions of everything and now we have 'specific covid' antobodies...!!!

And now covid PCR: it is officially ~40* times amplified ~16-24 nucleotide long piece of DNA(!!, not even RNA...) translated by polymerase from the present RNA virus which has ~30000 of the nucleotides enclosed in a spherical 3D structure. That alignment and translation is ONLY POSSIBLE AFTER BOILING the human tissue + viral+bacterial+fungal culture (everything what is at the back of the nose) in all the ~40 cycles, where the RNA falls apart and maybe recombines giving at the end complete nonsense Even a combination of few such pieces and adding known parts of viruses won't proof ANY INFECTION, which is caused by the ENTIRE LIVING (properly folded) virus at elevated BODY temperature of ~38degC, and not at ~100deg C. Taking a thermometer or oxygen meter measurements of anyone with SYMPTOMS is enough to tell one is sick, with OR without 'covid'! That's what the first german authopsies revealed, nobody died of covid alone, but 'with covid'..., even in a car accident...

Given all these details, any 'scientific study' using these 'determination methods' leading to any resulting statistics, should be equally questionable.

* normal amount should be 25-30