The Hep B vax HIV origin theory, pt. 2

Did the Hilleman vaccine amplify early cases in the US? Probably, no.

Turning to the question of amplification

In Pt.s 1 and 1.5 of this historical safari, a simple case was summarized and expounded for why it is implausible that HIV spread to humans via weird experiments involving co-circulation of chimpanzee blood with human patients as so provocatively proposed — the main family of the virus, 1M, which is so dominant in spread and pathology that it is basically synonymous with “HIV,” already had so much genetic diversity in 1980 that you could basically mistake it for any other endemic human virus. The only distinction is that in the first many, many decades of spread (in humans), the virus was only present in the Congo region (in very rare levels, limiting the phenomenon of recombination that occurs now rather regularly).

In a subsequent post, I may reckon with the question of the virus’s subsequent “pandemic”-era spread throughout Africa and perhaps China (i.e., can these be explained without extraordinary theories?); here in three parts the question will be confined to the West.

Summary of the case

The short summary of what will be argued, is that sufficient demonstration that trial recipients of the “First Hilleman Hepatitis B Vaccine” (FHHBV) did not develop HIV at a rate higher than the placebo group does not seem to exist (the trial was unblinded too early), but nor does evidence seem to exist that they did.

However, the process for producing the FHHBV makes it quite implausible that it was contaminated with any viruses even before extra sterilization; the FHHBV was trialed in dialysis patients and used in infants in New Zealand and elsewhere without apparent HIV outbreaks, which seems as good a proof as any; and in perspective the FHHBV even if contaminated could hardly have done more to disseminate the virus than events in Haiti in the 1970s, the practice of blood transfusion generally, and the known risk factors associated with outbreaks after 1978.

The Hilleman vaccine and HIV theory in context: We don’t care about development

Thus it is necessary to take stock of the coincidence of Hilleman and Merck developing and licensing a human-blood-based vaccine, with other entities performing trials of the same in between, at almost exactly the same moment AIDS became a recognized disease.

To clarify, the “First Hilleman Hepatitis B Vaccine” was a novel product produced from blood donated by chronically-infected gay, male Hepatitis B patients. Its creation was made possible by preceding years of careful, accurate characterization of the “antigens” associated with Hepatitis B,1 a virus which will be discussed further in a subsequent post, as its spread in the 20th Century has an interesting iatrogenic story of its own.

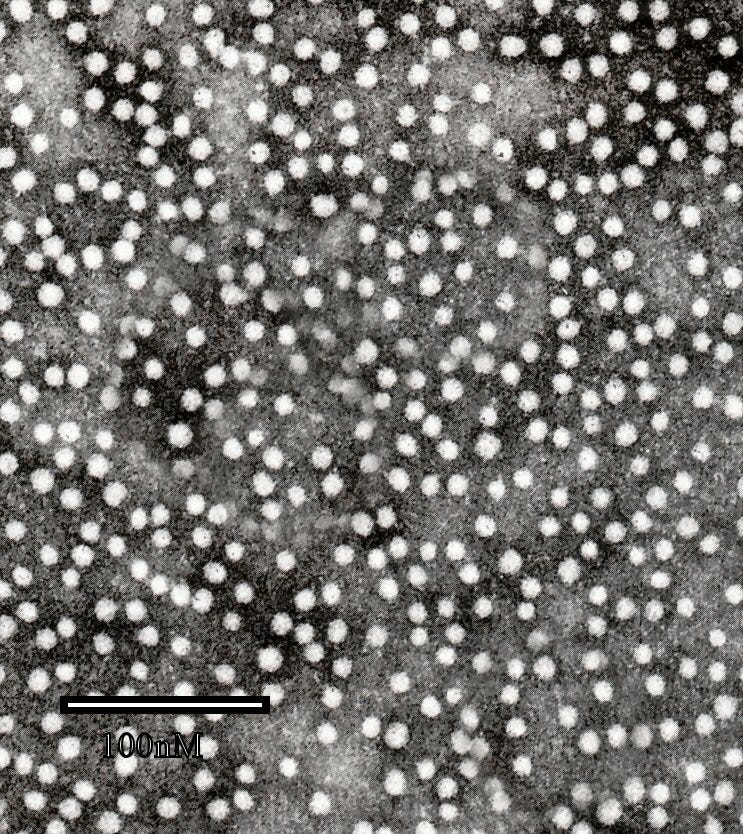

During acute and chronic infection, the majority of the same protein which studs whole viral particles tends to bud off from infected cells, into little spheres without any viral core — these protein-lipid spheres (lipoproteins), called the “HBsAg,” float all around in the blood.

Rather than try to make a vaccine out of whole virus, Hilleman and a few other labs set out to craft one from these little spheres which were found in chronic patients’ blood. How this was done will shortly be described, illustrating the implausibility of infecting anybody with HIV by this method, even if the patients were from an obviously high-risk group — i.e. even if they were infected with HIV. This led to the “FHHBV,” distinguished from a later version which simply coaxed yeast into producing the same particles via DNA recombination.

Regarding chimpanzees, this animal was chosen as test-subject for the first prototype of the FHHBV because it is susceptible to human Hepatitis B.2 This makes sense. No chimps were ever used to produce the FHHBV product itself. Our only concern, therefore, is whether HIV passed from infected human donors into the FHHBV and was distributed to recipients thereby.

As such, it cannot be the case that the FHHBV somehow was the “origin” of HIV. We only care whether it maybe amplified the scope of the early outbreak; in this post, as said, focusing on the West.

Insert: The NIH Purcell-Gerin Hepatitis B vaccine?

Of greater hypothetical interest, from a “coincidence soup” perspective, might be the simultaneous development of the Purcell-Gerin Hepatitis B vaccine at the NIAID Laboratory of Infectious Diseases, which resulted in the inoculation of 47 chimps with a human-plasma-based vaccine in 1976.3 These chimps were housed for at least another two years near Monrovia, Liberia, and one “Judy” was flown to New York for surgery in 1978. (By coincidence, one publication of the syndicated news story describing this curiosity was placed adjacent to a story regarding gay youth counseling.)

This may not have been the only competitor plasma-based vaccine in preclinical development around the time.4 Ultimately, the NIAID vaccine was purportedly never “field trialed” in humans nor considered for commercial use, though there does seem to have been some preliminary human testing.5 But given that Fauci was already a department head at NIAID at the time, one can imagine the endless possibilities for new theories… However, this coincidence, too, fails to refute the genetic and archival evidence of HIV’s long pre-existence in 20th Century Congo-region humans.

June, 1981: Why focus on the trials?

Just as the development and early animal testing of the FHHBV is not of interest, nor really is the actual licensing of the vaccine, i.e. its commercial use in the (high-risk) public — as this did not occur until June, 1981, weeks after the first headline for “an exotic new disease,” when the American AIDS outbreak was already crashing into view and retroactively assessed HIV infection rates were circa 20% and rising in New York and San Francisco. Ultimately, 850,000 Americans received the commercial version of the FHHBV by 1985.6 Whatever portion of these were gay men, vaccinations could not have outnumbered sexual interactions, and only the latter would have featured a self-amplifying risk of transmission vs. blood samples obtained in 1981 for the commercial vaccine.7

Therefore, we only care about what was going on before early 1981, when HIV prevalence was reaching a critical mass that would ensure widespread infection, and so we only care about the various trials which led up to commercial use. While it might be more likely in theory that vaccine production in the trial was more careful regarding purity and sterilization than the final product (especially given that the description of the process in 1976, as we will see, is compelling on this point), we may also entertain a hypothetical scenario in which the trial version of the FHHBV had contamination but later commercial versions did not.

The trials - slow and limited in high-risk groups

While the vaccine was developed and tested by Hilleman’s lab at Merck, the major trials were handled in a decentralized fashion. In the earliest stage, Hilleman himself appears to have begun human testing in volunteers as early as late 1976.8 But in his retrospective summary of the FHHBV’s human trials,9 the trials not cited to other investigators are limited to 336 medical personnel, 13 young children in Philadelphia suburbs, and 66 low-risk adults. The aim of these early tests was not to evaluate efficacy against infection — there was no way of doing so with such small numbers — but confirm and tune appropriate dosing strategies according to antibody response.

The delay in trialing the FHHBV in high-risk groups had to do with the complexity of the project — different risk groups for Hepatitis B presented different trial design considerations. Identifying, vaccinating and monitoring vertically infected newborns and intravenous drug users were logistically and ethically fraught prospects, for different reasons.10

Common to both dialysis patients (who at the time had formed a Hepatitis B infection network of their own) and to gays was the difficulty in figuring out how many were actually not yet infected — the vaccine cannot prevent infections that have already happened. Trials in these groups therefore were preceded by years-long screening efforts beginning in 1974.11 Once the screening gave an idea of how many Hepatitis B infection-naive individuals were available (quite few), recruitment efforts could be designed accordingly. For gays, two FHHBV trials in San Francisco and Amsterdam began surveying in 1978, but did not administer any vaccine until 1980. A CDC-run trial recruiting from venereal disease clinics in five American cities12 likewise did not start until that year.13

This leaves only one trial which got vaccines into shoulders before 1980, produced by the Lindsley F. Kimball Research Institute and Columbia University School of Public Health.14 This effort undertook screening between 1974 and 1978, recruiting from 13,000 screened gay men in New York city to find a whopping 1,083 volunteers who met requirements. Vaccination with the FHHBV began in November, 1978 and initial trial results included observations up to May, 1980.

A final mention may go to the study regarding drug users — Hilleman, et al.’s summary only mentions one, published in 1983.15 As this risk group is not suitable for a randomized trial due to the difficulty of follow-up, a (seemingly) single effort was made to observe antibody responses to the vaccine among a handful of users in recovery (and staff) in Rotterdam. 24 outpatient methadone patients from two recovery centers were joined by 21 inpatient detox patients from two other centers; only 14 of the outpatients completed the 6-month vaccination course.

Perhaps more studies were underway among drug-users in this era, but had not published their results by the time of Hilleman, et al.’s summary — it would hardly matter, since the vaccine used in this trial was the commercial version, marketed in June, 1981, when in other words drug users could already get the vaccine for themselves. If the FHHBV trials had any influence on the early spread of HIV in drug users, it would vastly more likely have been via participants in the gay male community who happened to also use intravenous drugs.

Thus, a prima-facie plausible, but not strong circumstantial case against the FHHBV trials

As said in the summary, nothing that was later published regarding HIV incidence in vaccine trial participants seems to obviously exculpate the FHHBV.

Multiple retrospectives were eventually published by the node of researchers who carried out the New York trial, combining results for those participants with results from San Francisco and Amsterdam.16 Another retrospective looks at just the San Francisco cohort in further detail.17

Since the FHHBV trials had resulted in the collection of samples during screening, vaccination, and follow-up, they had preserved a record of the HIV outbreak among participants (the whole point of the theory is that these events were timed perfectly). The report focusing on the San Francisco group alone shows that the first screening survey, in 1978, captured the last year in which the virus was rare in American gays:

Unlike for Hepatitis B infection, no comparison in HIV infection rates seems to be offered between participants randomized to receive the FHHBV and those who receive placebo (but I intend to keep reviewing, in case I have simply missed this). This omission is explained of course by the totally innocent presumption that both groups should have been equally at risk of HIV via community-acquired infection.

That leaves city-by-city comparisons, and whatever tenuous interpretations we might levy at the same.

As said, the New York trial initiated FHHBV-vaccination in 1978; San Francisco and Amsterdam in 1980. From the perspective of “exonerating” the FHHBV from having had a role in amplifying early spread, what we might hope to see is that New York’s trial participants don’t begin to experience HIV infection any more quickly than San Francisco. And this is what in fact is reported:

Failure to find a distinction between (half-vaccinated) New York and (screened, but not vaccinated) San Francisco participants in 1978-9 means these published results do not offer anything like a smoking gun.

Other elements of van Griensven, et al. and Hessol, et al. are consistent with the notion that FHHBV trial participants are being infected with HIV merely via sexual contact rather than from the trial vaccine. In Amsterdam and San Francisco, it is certainly conspicuous that after their trials begin (in 1980) cases either begin to rise or accelerate, respectively. But the similarity in San Francisco and New York seems better explained by the virus already existing and amplifying in a wide sample of gay men at those places — remember, trial participants are only a fraction of the whole community, and so New York’s trial participants could hardly drive the rise in San Francisco to mirror their own purportedly vaccine-derived infections without going through several thousand “middle-men”. And the difference between those two cities and Amsterdam seems better explained by the virus not already being seeded in the wider community, as well as by a (slightly) lower rate of reported anal sex.18

A less overwhelming, but still consistent further point against the theory is that in San Francisco’s more granular report, older trial participants (over 30 years old) become infected with HIV at a lower rate than those under 30. This, like the early rise in infections in San Francisco before vaccination begins there, is not explained well as some post-vaccine community amplification of vaccine-induced infections. If we are to accept a case that the FHHBV trial is amplifying community spread, any effect from community spread should be unnoticeable compared to direct infection from the vaccine, as, again, the trial only involves a fraction of the community. The difference in infection rates among young and old in San Francisco (measured in person-years) suggests that trial participants are being infected by the community at large, not the vaccine.

Ultimately, these reports are not overwhelming for either conclusion, especially with no comparison of HIV infections comparing vaccines and placebos in the first years.

We will therefore turn to other lines of evidence…

If you derived value from this post, please drop a few coins in your fact-barista’s tip jar.

This work would have been far easier if, at the time it was undertaken, medical practice and cultural changes had made it so easy to group high-risk patients together as in the mid and late 70s. Rather, in 1963 Baruch Blumberg had to travel 40 countries and sample 10,000s of people before identifying the “Australia” antigen (the HBsAg lipoprotein) from an aborigine.

Buynak, EB. Roehm, RR. Tytell, AA. Bertland 2nd, AU. Lampson, GP. Hilleman, MR. (1976.) “Vaccine against human hepatitis B.” JAMA. 1976 Jun 28;235(26):2832-4.

Graham, Victoria. (February 17, 1978.) “Chimp, Vital to Research, Gets VIP Treatment.” The Times Leader. p 2. newspapers.com

I have not yet gathered any published literature on the Blumberg “killed virus”/antigen-based vaccine which is reported in newpapers in 1976. It isn’t mentioned in the summary given by (Szmuness) below, and nothing under Blumberg or Millman’s name from 1976/7 mentions development of a vaccine.

As early as 1971 Krugman demonstrated that a vaccine against hepatitis B can be prepared by boiling diluted sera from chronic asymptomatic HBV carriers and that such a vaccine is safe, immunogenic, and protective [Krugman et al, 1971] . Subsequently, two more sophisticated vaccines were developed in this country: the NIAID vaccine [Purcell and Gerin, 1978a] and the Merck vaccine [Hilleman et al, 1978]. Both consist of highly purified and formalin-inactivated hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) particles, administered in aqueous or alum adjuvant formulation.

Szmuness W. (1979.) “Large-scale efficacy trials of hepatitis B vaccines in the USA: baseline data and protocols.” J Med Virol 1979;4:327-40.

Regarding preliminary testing, this is inferred from multiple newspaper reports in 1976. There may no longer be any record of this outside of NIAID or the researchers’ own documents.

Shaw FE Jr, Graham DJ, Guess HA, et al. (1988.) “Postmarketing surveillance for neurologic adverse events reported after hepatitis B vaccination: experience of the first three years.” Am J Epidemiol 1988;127:337-52.

Commercial vaccine preparation procedures are always harder to look up. In

Pépin, Jacques. The Origins of AIDS (p. ). Cambridge University Press. Kindle Edition.

Pépin references print and TV ads for plasma donors for the FHHBV targeting gay men in July, 1981. It is possible that donation continued in the same manner after 1982.

Cohn, Victor. (November 16, 1976.) “Pneumonia, hepatitis vaccine being tested.” Public Opinion (syndicating The Washington Post) newspapers.com

A flood of new or improved vaccines to prevent some serious illnesses — 41 new products altogether, including shots to prevent pneumonia and hepatitis — are now being tested in human volunteers, a federal scientist [William S Jordan, NIAID] reported this week. […]

Jordan and Dr. Maurice Hilleman of the Merck Institute for Therapeutic Research also described these new vaccines now being tested in humans against:

—Hepatitis B[…]

McLean, AA. Hilleman, MR. McAleer, J. Buynak, EB. (1983.) “Summary of worldwide clinical experience with H-B-Vax (B, MSD)” J Infect. 1983 Jul:7 Suppl 1:95-104.

(Szmuness W. 1979.)

ibid.

San Francisco, Los Angeles, Chicago, Denver, and St. Louis.

Francis, DP. et al. (1982.) “The Prevention of Hepatitis B with Vaccine - Report of the Centers for Disease Control Multi-Center Efficacy Trial Among Homosexual Men” Ann Intern Med. 1982 Sep;97(3):362-6.

Szmuness, W. et al. (1980.) “Hepatitis B Vaccine — Demonstration of Efficacy in a Controlled Clinical Trial in a High-Risk Population in the United States.” N Engl J Med. 1980 Oct 9;303(15):833-41.

Findings were updated 6 months later, without much change, in

Szmuness W. Stevens, CE. Zang, EA. Harley, EJ. Kellner, A. (1981.) “A controlled clinical trial of the efficacy of the hepatitis B vaccine (Heptavax B): a final report.” Hepatology. 1981 Sep-Oct;1(5):377-85.

What is interesting about the latter is that it cites what may be a more direct summary of Hilleman’s earliest human tests, which I haven’t been able to locate:

Hilleman MR, Bertland AU, Buynak EB, et al. Clinical and laboratory studies of HBsAg vaccine. In: Vyas GN, Cohen SN, Schmid R, eds. Viral hepatitis. Philadelphia: Franklin Institute Press, 1978: 525-538.

Schalm, SW. Heÿtink, RA. Mannaerts, H. Vreugdenhil, A. (1983.) “Immune response to hepatitis B vaccine in drug addicts.” J Infect.1983 Jul:7 Suppl 1:41-5.

van Griensven GJ, et al. (1993.) “Epidemiology of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection among homosexual men participating in hepatitis B vaccine trials in Amsterdam, New York City, and San Francisco, 1978-1990.” Am J Epidemiol. 1993 Apr 15;137(8):909-15.

Hessol NA, Lifson AR, O'Malley PM, et al. (1989.) “Prevalence, incidence, and progression of human immunodeficiency virus infection in homosexual and bisexual men in hepatitis B vaccine trials, 1978-1988” Am J Epidemiol 1989;130:l 167-75.

(van Griensven GJ, et al. 1993.) 74% in Amsterdam, 98-99 in New York and San Francisco.

Yet after a lifetime of work with the germ theory, Pasteur himself, on his deathbed said: “I was wrong. The germ is nothing. The Terrain is everything.”

"No chimps were ever used to produce the FHHBV product itself" contradicts what they had written in the patent.

https://patents.google.com/patent/US4118478A/enPlasma used as source material for the purification procedures detailed below is obtained by conventional plasmaphoresis procedures from chronic HBs Ag carriers. These may be humans or animal species such as chimpanzees in which the chronic HB carrier state can be induced. The chimpanzee offers the practical advantage that it can be infected with human hepatitis B strains of any desired immunologic sub-type, and can develop chronic carrier state infections which in our experience show particularly high titers of HBs Ag and are frequently associated with high concentrations of both Dane particles and e-antigen. Furthermore, these animals can be conveniently plasmaphoresed at frequent intervals without damage to their health or reduction in HBs Ag or e Ag content of their plasma.