The return of "defensive democracy"

The logic behind the mantra of "protecting our democracy" in the US

At Foreign Affairs this week, it is reported that Salvadoran president Nayib Bukele’s abrogation of the civil rights of criminal gangs has “eroded democracy.” And, as a result of these terrible acts of democracy-erosion, Bukele has gained nearly unanimous approval and won over ten times the votes of either of his opponents in last month’s election.

That a ruler whose actions represent the rule of the people has “eroded democracy” is a rather difficult claim to square with the lay and official definition of the word.

Democracy:

a system of government by the whole population or all the eligible members of a state, typically through elected representatives.

—Oxford languages

Likewise incoherent in this regard are Biden’s repeated sermons that democracy is under threat from a political opponent he refuses to name for fear of legitimizing — as if “democracy” describes the concept of allowing only certain, acceptable individuals and positions to enter the ballot or be debated publicly, a position in fact widely shared by elected officials and public servants of both parties and the media, and reflected in their efforts to remove Trump from the ballot and restrict speech.

The true meaning of this “democracy”: liberal demographic anti-majoritarianism

This inverted use of “democracy” is inconsistent with the modern American lexicon. In reality, “democracy” when spoken of in this sense — as something, some thing, which is under threat from the opinions and preferences of the demographic majority of the country — refers to what is typically called “liberalism” in this country. It refers to exactly what Foreign Affairs complains Bukele has attacked in concrete form to “erode democracy”: “basic civil liberties,” and “transparency, due process, [and] human rights.” But to bring the reality into even sharper light, it only refers to the maxim that those elements of political custom must at all times be granted to everyone, no matter who they are.

This is a more European understanding of “democracy,” and perhaps the dictionaries over there would render Biden’s speeches more coherent. Here, again, we could use “liberalism,” though even this is slightly imprecise. It is liberalism at one stage; the stage of dismantling, locally, tacit forms of demographic political hegemony, as during the Civil Rights era, or of resisting non-liberal political systems at home or externally. In this sense, it is “democracy” described as the system opposed to totalitarianism or communism.

Whereas the US sees its current political system as an evolution of classical liberalism, Europe sees its system as an evolution of a product of the early Cold War. This would make “democracy” a more natural description of what is under threat from “extremist” and populist movements; but in both continents the real threat is to “liberal demographic anti-majoritarianism” as put into practice in the 1960s and afterward — in other words, to anti-discrimination.

In both systems, the system of liberal anti-majoritarianism has been tolerated since the 1960s due to insulation from the real-world consequences. In the US, as I recently argued, the Civil Rights Era created an unstable condition, a regime which in fact was not tolerable to American whites over the long term and would perhaps have collapsed, but which was resolved by effecting covert apartheid, via the creation of a super-expanded prison system in which 4% of Black males were incarcerated at any given moment, and when not in prison could not count on their supposed civil rights when actually interacting with police, and yet before 2012 the news didn’t talk much about it. In Europe (as well as in wealthy communities throughout the United States), endogenous demographic homogeneity rendered liberalism something of a “luxury belief.”

Here I must in a way restate the previous paragraph: The liberal concept of civil rights was first put into political practice in a purely discriminatory context; America was a nation in which one race was almost entirely enslaved by the other, and the franchise in founding-era states was limited to white, male, land-owners. There is no real sense in which demographically bounded anti-majoritarianism, in which only some types people actually enjoy “universal” civil rights, is a paradox from the point of view of the American inception; it was the American inception. The transition to (unbounded) demographic anti-majoritarianism, when civil rights are truly universal, can only be called a “realization” of the American vision in the sense that universalist theory was used to describe and justify a totally different system; taking away imprecise rhetoric, the Civil Rights Era was simply the transition between one design for society to a different one. However, it is important to understand that this transition was demanded by the language of the founding (because it did not match the system actually put into place); that it does in fact represent the true meaning of “liberalism.”

LDaM: A system failing as soon as it is put into practice

The point of that rather untidy tangent is that the thing being called “democracy” in the West — the maxim that civil rights and public goods must at all times be granted to everyone, no matter who they are — is not a feature of the “American tradition” in any sense except the notional one. It wasn’t the practice of American society at the time of the founding, before the Civil War, during Jim Crow, during the Great Migration, or even after desegregation. While it has long been prized as the virtue supposedly responsible for American economic and intellectual accomplishments (surely a surprise to the German immigrants who were all forced to change their surnames to live here a century ago), it is only seriously being tried now; and after only a few years the system is disintegrating.

The same may be said of Europe: As soon as this core idea of liberalism has actually been put to the test thanks to widespread migration, European “democracy” is disintegrating.

Now we may examine why the response to this failure of demographically universal civil rights has been to resurrect a Cold-War era notion of “democracy,” and to suppress civil rights.

The return of “defensive democracy”

It is difficult to understand “defensive democracy” from the American perspective. After the term “McCarthyism” was coined in 1950, the senator himself embraced it and defined it as “Americanism with its sleeves rolled.” But McCarthy and Congress’s violations of civil rights in the name of anti-communism were quickly rebuked by the public and by the intelligentsia. Within another decade, “leftism” was an ascendent force in American culture and politics, reflecting the passive attitude of our culture toward the threat of anti-liberal political orders (even though, at the time, the FBI still carried on the McCarthyist or Trumanist project covertly). America in fact prefers its sleeves to the wrist. Democratic liberalism was supposed by thinkers in the post-McCarthy era to always survive by winning in the “marketplace of ideas,” as we will explore further below.

Free Europe in the early Cold War was on the other hand only a few years removed from Naziism and a few borders from Soviet communism. For this reason, the notion of a “democracy able to defend itself” was built into the European Convention of Human Rights. This document, like McCarthyism, was also something of an anachronism by the 1960s; and when it rose into prominence afterward as the modern “European bill of rights,” it was serving an intention that was secondary to its drafting. But at the time of drafting, the primary concern was to prevent the return of Naziism or infiltration of communism, and the mechanism for doing so was not to trust the “marketplace of ideas,” but to create a legal concept in which anti-liberal politics are an “abuse” of rights.

This “self-defense” mechanism of liberalism is Article 17 of the ECHR, which reads:

Prohibition of abuse of rights

Nothing in this Convention may be interpreted as implying for any State, group or person any right to engage in any activity or perform any act aimed at the destruction of any of the rights and freedoms set forth herein or at their limitation to a greater extent than is provided for in the Convention.

To translate this to an American context, one may imagine that in the early Cold War, an amendment was added to the Constitution to clarify that none of the rights listed earlier apply to “anti-Constitutional” dissent. Further restrictions were inserted directly into the ECHR’s provisions for free speech and privacy, which have given the green light to Europe’s many laws against hate speech — in essence, “discrimination” itself is not a right in modern Europe.

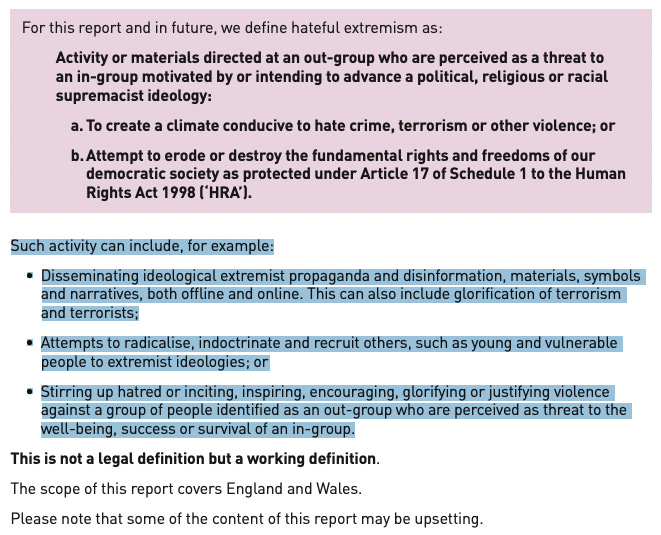

Article 17 is now being put into practice in the UK, which imported the ECHR into its own legal system wholesale with the 1998 Human Rights Act. Thus when one reads the UK government’s draconian new definition for “extremism,” issued last week, one learns that the definition was crafted based on recommendations from a 2021 report by the government’s in-house think-tank on the topic, and that this report invokes Article 17 to justify a maximalist definition of unprotected conduct:

Europe’s widespread but precarious suppression of dissent is not solely a crisis of liberalism — it is also a crisis of the West’s lack of faith in itself, of elite-overproduction, and of a million other problems — but when understood as a crisis of liberalism it is valuable to perceive that the apparent paradox, that of liberal governments suppressing civil rights to protect “civil rights universalism,” is in fact right in line with the vision of those who crafted Europe’s bill of rights. As Ed Bates writes in his history of the Convention:1

The primary aim of those who drafted the Convention in 1950 was to create a type of collective pact against totalitarianism […]

We shall see that the first ambition of the Convention’s proponents in 1949 was to institute a European scheme that was primarily intended to act as a type of ‘alarm bell’ for democratic Europe. The initial idea was to create an international mechanism by which ‘free Europe’ could protect itself against the rise of another Hitler, or the installation of a totalitarian regime.

This is the notion of “defensive democracy;” the central court at Strasbourg, which hears cases related to violations of the convention, has often affirmed this founding logic in interpretation, supporting the criminalization of ostensibly protected acts in the name of “democracy defending itself” (see the ECHR’s guide to Article 17, in which the word “democracy” appears 36 times).

Early Cold War logic also explains Biden’s almost fetishistic obsession over “protecting our democracy,” as one can see by the list of how often presidents have mentioned “democracy” in their inaugural address:

Thus, we have reentered the conditions which require “defensive democracy.”

Seeing things in this light should make clear the futility of fretting over the hypocrisy that seems to lie at the heart of elite restrictions on speech which in fact are widely popular among much of the public. The question is not whether preserving the current order requires the harm of “protected” rights to expression and assembly, but only whether elites will accept a return to de facto non-universalist liberalism.

To do so, white, Western elites must realize that the social vision which wins in the marketplace of ideas — liberal demographic anti-majoritarianism — is the wrong one.

The core fiction of “democratic liberalism”: Winning in the marketplace of ideas

This brings us to the true paradox that has led liberalism to this crisis. If the transitional period between McCarthyism — “Americanism with its sleeves rolled” — and the Civil Rights Era is to be seen as the time when modern liberalism formed its kernel code, the rationalist logic upon which all future rhetoric and belief was obligated to build, then this is also the time when the fiction of self-sustaining democracy was given form.

This fiction is criticized by James Burnham in Suicide of the West. In this essay, published in 1964, he dissects what modern American liberalism must be by defining the beliefs that would be required to explain what contemporary liberals say and do not say. At that time, it was clear that the world had reached two alternate end-points of rationalist political thought — designing society and governments according to reason rather than tradition — one being liberalism and the other communism. American liberalism however had come to understand itself as self-sustaining, as something that was inevitable and required no will to preserve. This itself was of course a paradox; as at the same time armed force was still being deployed to force white Americans to accept the results of desegregation. But there was a faith in place, still, that a system not founded explicitly on suppressing dissent must anyway survive long term, once these troubles are over.

How was this so; i.e., what beliefs must have become part of the liberal consciousness to produce this faith?

Here I will offer my own summary of the first half of his list:

Man’s nature is not fixed, and is improvable (the only sin is ignorance)

Rational thought drives material progress and problem-solving; the liberal as rationalist is defined by Oakeshott as “the enemy of authority, of prejudice, of the merely traditional, customary or habitual.”

Since human nature cannot impede the improvement of society, the only obstacles are external, principally ignorance and bad social institutions

Progress is inevitable (historical optimism; the tendency to see all issues as “problems”)

Since external obstacles are legacies of past, all traditions are intrinsically without value or even negative

To combat residual external obstacles, what is needed is universal, rationalist education (education cannot be in service of forming model citizens in either a social or nationalist / cultural context)

Next, what is needed is democratic politics; educated man will effect the most desirable outcomes automatically

Since external obstacles are responsible for all ills, disadvantaged individuals and groups are not responsible for crime

Education, in order to be rationalist and to eradicate ignorance, must be a “free forum of ideas”

Democratic politics must be no different, as it is merely the practice of education in the world. “Wrong” ideas, which cannot be defined a priori anyway, must be allowed a place in any debate

Paradoxically, however, it is axiomatic that whatever idea becomes accepted in the market of ideas under these conditions is the most likely to be true, but attainment of the closest state to truth is only possible with perpetual tolerance for dissent

The most critical belief Burnham identifies is a more basic faith in reason and education.

Reason and education however are not in fact safeguards for free speech. In a way it is almost the opposite — free speech is a safeguard for sustaining a consensus faith in reason and education.

More accurately, as long as the “marketplace of ideas” is allowed to pulse along freely within a demographically homogenous society, or one in which one people is unfairly privileged over others, it will produce liberal ideas, including especially the idea that civil rights and public goods must at all times be granted to everyone, no matter who they are.

It is impossible to justify hierarchy and exclusion in the “marketplace of ideas” — they are, after all, at all times and places products of tradition laid over raw power and violence.

To preserve liberalism in practice, therefore, the theory of liberalism must be completely reformed. The founding logic — faith in reason and education — must be replaced with a restoration of tradition. And white societies must no longer nonsensically be asked to enjoy living as “just another minority” in their own lands, as if it were for this reason, this ultimate rationalist end-goal, that they were put on earth.

Until this happens, there will be no government of white society that does not suppress free speech. “Defensive democracy” will be the only flavor available, going forward.

If you derived value from this post, please drop a few coins in your fact-barista’s tip jar.

Ed Bates. (2010.) “The Evolution of the European Convention on Human Rights.” OUP Oxford.

Dunno if you've listened to Mike Benz, but he has a hypothesis that a major disconnect between the hoi poloi and the powers that be is the former conceptualize democracy as a popular vote whereas the latter conceptualize it as "institutional consensus". I think this gels with the circling of the wagons we're seeing institutions engage in when criticized.

The Elite theorists were correct: democracy is a myth. A well organized minority (elite) will inevitably rule a disorganized majority (masses). Furthermore, ideology is subordinate to power–i.e., rationalization is post hoc.

If one accepts this view (which I do), then the day-to-day operations of those who exercise power and influence become clear to see and understand. And, even, dare I say: ‘sensible'.

Therefore, YES, democracy is exactly what they (the elites) say it is. Same for liberty, equality, human rights, etc.

So—What is to be done?

“Clear them out!”

This, of course, does not guarantee that a new cadre of elites will be any better.

In the meantime, our power lies in building small and strong.