The Origin of Lockdowns

Lockdowns occurred because they gave scared, (literally) non-essential Western professionals “something to do.”

This post contains an appendix which deals with questions of originality. In short, this is not meant to be an original thesis, merely a review of history, both obscure and obvious.

The reigning understanding of lockdowns

Recently, Igor Chudov defended the “conspiratorial origin” of lockdowns in a well-sourced post:

Bill Gates, as well as the World Economic Forum, had a pandemic plan. How do we know? Very simple, their plan was public. Here’s the video from the WEF where Bill Gates [on April 3, 2020] explains their plan!

But as one who harbors a belief that a globalist deep state is the most likely culprit behind development of the virus and the vaccines for the same, the claim that any external entity was behind lockdowns and mask mandates doesn’t strike me as plausible. My perception of these charades at the time and afterward is that they were, in fact, media-sparked mass panics merely codified “after the fact.”

Everyone in the West suddenly became afraid to go outside at the same time; for weeks at a time. The instant some sort of logic for transforming this fear into an “action” was finally discovered — “flatten the curve,” a.k.a stay inside and stay afraid — the fear gained a legal imprint. Lockdowns and mask mandates were born. Current attempts to blame the government for past and present lockdown tolerance are simple bargaining to escape the reality that fellow citizens were and are our jailers in the lockdown era, as in every era of mass, moral panic. The Salem Witch Trials did not happen because the local Anti-Witch Party rigged an election.

On account of finding an “emergent” origin theory of lockdowns both plausible and irrelevant to the question of conspiratorial origins of the virus (and injectable countermeasures), I was knocked flat by the recent Michael P Senger post purporting to reveal that one Zeynep Tufekci, of all people on Earth, apparently unleashed the phrase “flatten the curve” upon us all:

Zeynep’s [Tufekci uses her first name as her twitter handle, so I will use it to refer to her going forward, as Senger does] first article on COVID appeared on February 27, 2020, in which she stressed the importance of getting ready for major disruptions during COVID in order to “flatten the curve.” She was among the first individuals to ever use the term “flatten the curve” with regard to COVID, though the term had occasionally been used during prior virus scares.1

Senger goes on to implicate Zeynep and her collaborator as the masterminds behind mask promotion and mandates. This analysis is frankly non-compelling, given that mask mandates operated as dead letters during most of 2020, only to re-emerge when it was “safe” to evince concern about something other than race and gender again, post-election day. As with his book Snake Oil, Senger seems prone to constructing fantasies in which the West is not responsible for its own insanity, but is instead the victim of mysteriously powerful foreign voices whispering suggestion.

Meanwhile, the striking fact of Zeynep’s preternaturally early articulation of “flatten the curve” — a phrase whose memetic potency did in fact seed the insanity of lockdowns in the West — is not returned to in his post.

Yet in her February, 27 Scientific American article, this magnetic phrase — which has no real provenance in epidemiology, as will be shown below — appears 6 different times:2

In contrast, the real crisis scenarios we’re likely to encounter require cooperation and, crucially, “flattening the curve” of the crisis exactly so the more vulnerable can fare better, so that our infrastructure will be less stressed at any one time.

All this means that if we can slow the transmission of the disease—flatten its curve—there will be many lives saved even if the same number of people eventually get sick, because everyone won’t show up at the hospital all at once. Plus, if we can flatten that curve, there is more time to develop a vaccine or find antivirals that help.

All of this means that the only path to flattening the curve for COVID-19 is community-wide isolation: the more people stay home, the fewer people will catch the disease. The fewer people who catch the disease, the better hospitals can help those who do. Crowding at hospitals doesn’t just threaten those with COVID-19; if emergency rooms are overwhelmed, more flu patients, too, will die because of lack of treatment, for example.

Here’s what all this means in practice: get a flu shot, if you haven’t already, and stock up supplies at home so that you can stay home for two or three weeks, going out as little as possible

Mere weeks later, the phrase “flatten the curve” — which barely existed before her article — had exploded on social media and crystalized the case for the shutdown of Western society, opening the gates to a dystopia of nearly global totalitarianism (which for whatever reasons proved ephemeral and transient).

The Life of Zeynep

And so, who even is Zeynep Tufekci?

Rather than recycle her curriculum vitae, I will offer my personal interpretation.

Zeynep is a brilliant intellect who had the misfortune of achieving success as an intellect in a pan-global professional community defined by fatuous idiocy. Her career is therefore devoted to attempting to somehow save this community from itself, or rather from the populist revolt it so obviously has been courting. This quest has animated some number of intelligent, hyper-nuanced, and self-contradictory positions on her part.

For example, Senger highlights her apparent coy endorsement of state censorship in 2018, in which Zeynep is all-but writing the playbook which Western governments and social media would use to control speech in the years of the “pandemic”:

Even when the big platforms themselves suspend or boot someoneoff their networks for violating “community standards”—an act that doeslook to many people like old-fashioned censorship—it’s not technically an infringement on free speech, even if it is a display of immense platform power. Anyone in the world can still read what the far-right troll Tim “Baked Alaska” Gionet has to say on the internet. What Twitter has denied him, by kicking him off, is attention.3

Missing from Senger’s review is the preamble to her Wired essay, in which she articulates all the ways that social media has intrinsically and violently disrupted speech as an impliment of sociopolitical enfranchisement:

FOR MOST OF modern history, the easiest way to block the spread of an idea was to keep it from being mechanically disseminated. Shutter the newspaper, pressure the broadcast chief, install an official censor at the publishing house. Or, if push came to shove, hold a loaded gun to the announcer’s head. […]

Or [today, when governments have no chokepoints to control speech] let’s say you were the one who posted that video. If so, is anyone even watching it? Or has it been lost in a sea of posts from hundreds of millions of content producers? Does it play well with Facebook’s algorithm? Is YouTube recommending it?

Zeynep is recognizing that social media has both disempowered traditional authority in gatekeeping what can be said, and replaced it with a hyper-democratic, Athenian mob which keeps the gate of what can be heard. Are these concerns not seminal to the “right” — to traditionalists, Christians, and nationalists?

Of course they are — that is exactly Zeynep’s point: Social media is tormenting humanity and society, and courting a backlash that will aim pitchforks at everyone in the professional class. But, there is a humble and half-forgotten tool that can intervene, and stave off catastrophe: Grassroots, progressive government regulation.

But in fairness to Facebook and Google and Twitter, while there’s a lot they could do better, the public outcry demanding that they fix all these problems is fundamentally mistaken. There are few solutions to the problems of digital discourse that don’t involve huge trade-offs—and those are not choices for Mark Zuckerberg alone to make. These are deeply political decisions. In the 20th century, the US passed laws that outlawed lead in paint and gasoline, that defined how much privacy a landlord needs to give his tenants, and that determined how much a phone company can surveil its customers. We can decide how we want to handle digital surveillance, attention-channeling, harassment, data collection, and algorithmic decisionmaking. We just need to start the discussion. Now.

The Two Minutes Zey’p

Zeynep makes a convenient target for attacks from right-aligned “intellectuals,” because her anti-populism is apolitical; rather, it drives a pro-class authoritarian bent that sees all problems as something for the professional class to figure out on behalf of government and in the name of self-preservation. What is helpful to bear in mind is that most of her critics are among those she seeks to protect — they are credential-havers.

This is why, as explored below, she is “at the scene” as “flatten the curve,” the meme which crystalizes lockdowns, is formed — she accurately perceives it, sometime in late February of 2020, as the “solution” that the professional class needs to deliver to the hopelessly adrift governments of the West. To Zeynep, the “pandemic” is just one more crisis the professional class has brought upon itself — and her — by its modern ineptitude.

The modern right tends to posture itself in opposition to a cosmopolitan, globalist “professional managerial class” elite. As such the right tends to invoke localism in economic and political realms. Yet both the cosmopolitan left and localist right are girded to the same, broader superstructure. One way of understanding this superstructure is what Jon at Notebooks of an Inflamed Cynic refers to as the “prestige nexus”:

One friend of my parents, despite most of his family coming around, still clings intently to “the narrative” (or what at least could have genuinely been called “the narrative” a year ago). This is despite being a moderate conservative, independently wealthy and retired person with no direct “skin in the game”. Why?

The explanation I would propose is that he does have significant, indirect “skin in the game” despite nothing which would obviously tie him to the sinking ship of Covid policy.

You see, he is wealthy, has “family money”—buildings are named after his grandfather at “local elite university” money. […]

You see, as a man raised in wealth, he learned that his wealth really didn’t depend so much on the number in his bank account as his status within the “nexus” of mutually reinforcing prestige institutions.

This nexus is composed of the “mainline” media, academy, churches and NGOs, the government bureaucracies, medicine, Hollywood, the S&P 500 c-suite and banks, (and newest members) "big tech".

They all punch far, far above their deserved weight in terms of social influence because they all mutually reinforce each other. They act and react as an organic whole which gives them a dominant advantage against other would be social influences.

So the old adage “it’s hard to get someone to believe something when his salary depends on him not believing it” is best extended to “it’s hard to get someone within the nexus to believe something when his membership/good standing depends on him not believing it”.

Once you recognizes this basic dynamic things like the virus hysteria, weird ritualized invocations of climate change, “cancel culture” etc. All fit together seamlessly.

I would describe this “nexus” as a tenuous, global social consensus throughout the “Yank-osphere” — including America and its patrons in Europe, Central and Southeast Asia, the Pacific, et al. — which agrees one day at a time to pretend that all these people, everywhere, who don’t work with their hands actually have some sort of competence. The credential-havers who have (virtual or real) desks assigned to them at both the local and urban scale deserve to bring home a paycheck for just sitting in chairs and flinging words left and right, because they have credentials.

This agreement is necessary because the West, or the Yank-osphere, has for the last two decades at least operated as a sort of self-running Target store, where the trucks just sort of “show up” at the back on their own, and the shelves are always sort-of-stocked, and things are always sort-of OK, except for the gangs of thieves that infiltrate the aisles from time to time. No one knows where the trucks come from; no one remembers who designed the little machines that make receipts; everyone’s job is either to design signs or restock candles. The political “right” and “left” are in practice a meaningless pageant of division between department managers and corporate; both of whom are allied in interest against the employees without credentials.

To be fair, if a populist revolt does happen, the whole store would probably fall apart; but it remains the case that no one “in charge” actually knows what they are doing, or deserves their job. All they know is the names and roles of the others in their class, the other people “in charge.”

Zeynep, in my interpretation, perceives the peril and the sensibility of a populist revolt, and prescribes actions to the professional class accordingly.

Her 2018 Wired post is not defending censorship qua censorship; but as a last-ditch measure to cure an ill the professional class is inflicting on humanity.

Her frequent and borderline rabid advocacy for vaccines on twitter, likewise, is a defense of the (credentialized) authority of modern medicine which has wantonly and shamefully staked its reputation to vaccines in absence of actual proof that humanity is somehow any better off for injecting aluminum and microbial peptides into itself from birth.

Her acrobatics on masks — adopting the government’s contradictory “don’t use masks, healthcare workers need them” line in her February 27 Scientific American article only to take to the New York Times to chide the government for the same messaging a few weeks later4 — merely reflects that when no other solution is possible, she simply acts as avatar for the professional class status quo, a.k.a. the exact same “authorities” she later declares untrustworthy.

And her embrace of “flatten the curve,” in early 2020, was likewise a “concern troll-”esque attempt to save the professional class from itself — and, as it turns out, irrelevant to the emergence and global conquest of the meme.

The Murky Timeline of “Flatten the Curve”

Somehow, Zeynep’s visionary, but mediocre Scientific American article on February 27 is entirely missing from the history of the “flatten the curve” meme published by Fast Company a mere two weeks later, after the phrase had suddenly, successfully shut down the West.5

There is a good reason for this: Her article was irrelevant to the course of events that led to the phrase’s dominance.

The actual timeline of “flatten the curve,” as the Fast Company article describes with a measure of spin, is the quintessential artifact of the farce of our global math-panic:

Stage 1: Awakening the F-bomb

In 2007, in the wake of the bird flu panic of two years prior, the CDC published an “interim” guide for a national response to a future influenza pandemic. This included “Figure 1,” a modeled graph of two arbitrary, imaginary curves, and notations which included a reference to healthcare demand:

The phrase “flatten” appears in this report in the following context:

Each of the models generally suggest that a combination of targeted antiviral medications and NPIs can delay and flatten the epidemic peak, but the degree to which they reduce the overall size of the epidemic varies. Delay of the epidemic peak is critically important because it allows additional time for vaccine development and antiviral production. However, these models are not validated with empiric data and are subject to many limitations.

The War on Terror-era CDC report bears no authors list, but credits dozens of organizations for input.6 It is unclear what organization or individual devised the rationale which Figure 1 seeks to illustrate.

This image was recycled in the revised edition of the CDCs guide document, published (conspicuously) in 2017. However, the phrase “flatten” was removed from the document text, replaced by “slow down the spread” in the section regarding school closures.7

Sometime in late February, 2020, the (arbitrary and imaginary) logic behind point 2 — non-pharmaceutical interventions are intended to (maybe, non-emperically) tamp surges of demand on healthcare — in the 2007 graphic gained the attention of Zeynep and two staff at The Economist. Zeynep’s awareness of the meta-concept which would be termed “flatten the curve,” which would prompt her Scientific American article, seems to dawn on February 25:

However, an article in The Economist would appear on the exact same date as Zeynep’s Scientific American post, and this would likewise use the phrase “flatten the curve” multiple times.8

With sars-cov-2 now spread around the world, the aim of public-health policy, whether at the city, national or global scale, is to flatten the curve, spreading the infections out over time.

This has two benefits. First, it is easier for health-care systems to deal with the disease if the people infected do not all turn up at the same time. Better treatment means fewer deaths; more time allows treatments to be improved.

Both articles seem to have taken about two days to write and publish. The Economist’s is the one which is credited for incepting the meme (and graph) into wider consciousness.

The history of how “flatten the curve” emerged in (some corner of) elite media consciousness in late February still lacks an official account and seems mysterious in retrospect. A webpage belonging to one Peter Sandman, https://www.psandman.com/col/corona3.htm, dates itself to February 4, with a first Wayback Machine snapshot on February 18:

Zeynep seems to be articulating this same managerial “risk communication” mindset in her February 27 article; but so are the two authors in the simultaneously uploaded Economist piece, to an audience roughly ten times the size of Zeynep’s. Both seem to have internalized Sandman’s advice, whether they encountered it directly or whether the advice was already percolating in extra-state intellectual and “expert” circles.

Overlord… Peter? Literally who is this guy. (https://www.psandman.com/index.htm#about) The Economist article, unlike Zeynep’s, went so far as to reproduce the graphic from the CDC’s 2007 and 2017 report, while also appending the “flatten the curve” meme in the text (with “flatten” used seven times, unlike Zeynep’s six).

Now all the pieces were in place, but not on the graph. Rosamund Pearce had reproduced the CDC graph for The Economist in an article which advocated for “flattening the curve,” but she hadn’t included the (imaginary) logic behind the graph — modulating healthcare demand — on the thing itself.

Stage 2: Enter the Drewgon

Fast Company recounts how Pearce’s reconstruction of the CDC graphic immediately caught the attention of a public health wonk who had previously employed the same graph as a “pandemic preparedness trainer”:

Drew Harris, an assistant professor at the Thomas Jefferson University College of Population Health, was staying with his wife and daughter at an Airbnb in Oregon, when he came across the graphic in The Economist, as first reported by the New York Times. It was immediately familiar because he, himself, had used it a decade earlier in his work as a pandemic preparedness trainer. Working under a grant from U.S. Health Resources, Harris visited hospitals and talked to healthcare workers about the importance of preparing for the worst.

Harris, astoundingly, was so struck by seeing a reproduction of the graph that he somehow couldn’t figure out how to re-acquire the original via a Google search. He took to twitter with a manually-created simulation of the CDC’s original simulation, and, finally bringing the “flatten the curve” concept to its final form, added an imaginary dotted line for “healthcare capacity.”

While Harris couldn’t find his original graphic after reading the Economist, he loaded his laptop, late at night, and opened Photoshop to recreate it. But he grew too frustrated with the software, so he gave up and loaded Keynote. He had to freehand a lot of the graphic on his trackpad, so the curves weren’t crisp. His daughter mocked its lack of polish. And he shared it on Twitter anyway.

And then, well…

Nothing really happened at first.

Zeynep, Pearce, and Harris had independently and collectively produced the blueprint for the meme that would take over the West; but the West was still not ready for several days afterward.

But when the meme was embraced, it was in “knock-off” versions of Harris’s crude drawing from all corners of mainstream media and social media, which restored “math-y” computer-generated curves to the image while retaining his imaginary healthcare capacity threshold and overall cartoony approach.

“Flatten the curve” had no epidemiological provenance

Before reviewing the widespread embrace of the meme in early March, it is important to establish that nothing about the graph was based on “science” to begin with. The story of how “flatten the curve” came to be mis-understood as some type of established wisdom in “pandemic preparedness” is an accident of the whims of Pearce and Harris, as Fast Company reports.

First, Pearce, in reproducing the graph, did not want to take liberties with the CDC’s original documentation — as if that documentation was actually based on any sort of evidence to begin with. In fact, she cites the essentially arbitrary nature of the CDC’s graphic as the rationale for why she had to reproduce it exactly (before passing it off to Economist readers as some sort of official piece of “scientific” knowledge about pandemics):

“The difficulty with these diagrams is showing uncertainty. Even though it’s a diagram of a concept and not a model from real data, it’s easy for people to interpret it as a precise prediction, as it looks like a chart and we’re used to charts being precise,” says Pearce. “Once you’ve drawn these shapes, they look authoritative, even if they’re intended to be illustrative. That’s why I keep as close to the CDC’s as I could.”

Harris, as a Masters of Public Health-haver and receiver of US Health Resources grants, felt no such compunction:

“I added an extra line to it,” says Harris. “Apparently, that made all of the difference.” That extra line was the dotted “healthcare system capacity” line. And to be clear, it was fully a theoretical invention. There is no telling whether, even with the proper amount of handwashing, we won’t overload our healthcare system with any given unique pandemic. He didn’t count beds or respirators. He just drew the line.

Harris, interviewed in the New York Times for his invention of the dashed line that shut down the world, claims:9

“Folks in the preparedness and public health community have been thinking about all of these issues for many years,” Dr. Harris said in an email. “Understanding and managing surge is an important part of preparedness.”

But was it? As reviewed above, the term “flatten” was dropped in the CDC’s 2017 revision of their pandemic response guidelines. Pubmed searches for the word “flatten” in years between 2007 and 2020 do not turn up results related to pandemics or viruses.

On the other hand, despite dropping “flatten,” it is true that the 2017 revision doubles down and fleshes out much of what the “interim” 2007 document proposed by the same phrase. School closures, government promotion of telecommuting, social distancing, and “cancelling” mass gatherings are all mentioned in Figure 5 with the “expected outcome” of “reduced load for health care facilities.” An accompanying review document includes 475 studies (either directly or nested in meta-reviews, including Cochrane’s), with several under the category:

Social Distancing Measures for Schools, Workplaces, and Mass Gatherings

Even though the evidence base for the effectiveness of some of these measures is limited, CDC might recommend the simultaneous use of multiple Social Distancing Measures to help reduce the spread of influenza in community settings (e.g., schools, workplaces, and mass gatherings) during severe, very severe, or extreme pandemics while minimizing the secondary consequences of the measures.10

The studies or meta-reviews included are heavy on modeling; however, 2017’s revision includes a bumper crop of real-world papers regarding the 2009 “flu pandemic,” chiefly out of Asia where closures were often applied, which adds a gloss of “empirical” evidence to the revision that is absent in the 2007 version.

None of these facts about the 2017 revision to the CDC guidelines lends the concept behind “flatten the curve” the authority and self-assuredness with which it was sold to the public in 2020. And this discrepancy is because it was not sold to the public by the CDC, or anyone within “science” to begin with.

No one in “expert” circles would have dared to actually propose or enact the CDC guidelines with the justification of maybe, based on sort-of a few studies and models that some people did, we think, possibly “slowing down” spread.

Instead, “flatten the curve” was sold by the public to itself.

Stage 3: The revolution of the self

Harris’s revolutionary graphic landed with a whimper, rather than a bang, accruing a mere 920 retweets to date. It was the more polished, animated reproduction by New Zealand journalist Siouxsie Wiles which set the globe on fire:

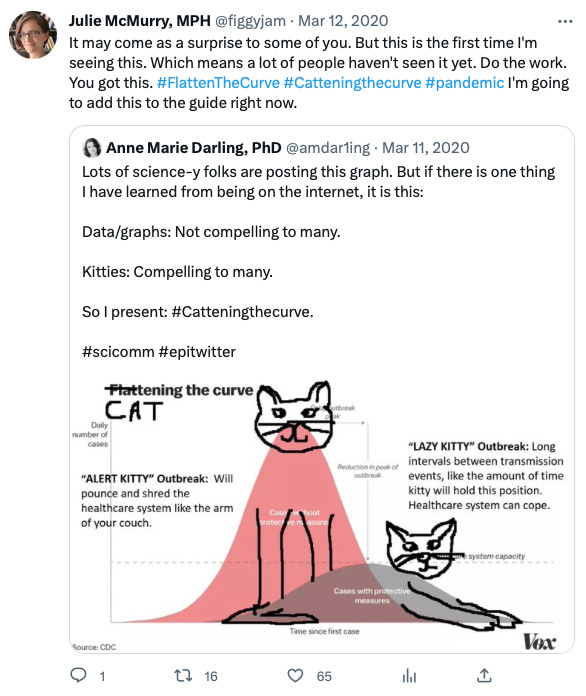

Pearce breathed new life into the CDC graphic. Then Harris added an anchor, a single line, that articulated its significance. But it was Dr. Siouxsie Wiles who took the final step: She demonstrated the possibility that everyday people really could make a meaningful difference in slowing the spread of COVID-19. To do this, she transformed the graphic into two futures, each caused by a mentality: ignore it or take precautions. Wiles transformed the graphic into the perfect response to the polarized nature of COVID-19 across social media, in which people were either in full prep mode or far too skeptical that the pandemic was even real.

Is this really the explanation for why her graphic became viral, being shared millions of times, and prompting the explosion of imitators and the #flattenthecurve hashtag? Or had Wiles simply latched onto the “flatten the curve” meme at exactly the same time, and for exactly the same reason, as great swathes of the West suddenly needed to do the same? Because it appeared to make things “manageable.”

The most insightful examination of the West’s “flatten the curve” psychosis, perhaps, appears in a post from five days later in SELF, penned by editor-in-chief Carolyn Kylstra:

With the simple url of “flatten-the-curve,” the post resonates with revelation. A vision, a promise, has appeared in Kylstra’s mind; “flatten the curve” has flashed through the darkness like lightning from heaven (emphasis added):

Over the past few days, numerous friends have asked my opinion about what they should or can do in light of the new coronavirus. Is it okay to go to the movies? Fly to a wedding out of state? Hang out with their 74-year-old immunocompromised mother at a child’s birthday party? They don’t know what to do, and they’re definitely not alone in their confusion.

It’s completely reasonable to be confused right now—unfortunately, we’re getting all sorts of mixed messaging from our top government officials, and the response from local policymakers and business owners has been piecemeal, rather than coordinated. I get the feeling that everyone is kind of just looking around, waiting for someone—anyone—to tell them what to do.

If you feel this way, here’s what I’ve been telling my friends looking for a solid answer: We all need to practice social distancing as much as we can, starting as soon as possible.11

Lockdowns were not imposed by Western governments, any more than witch trials. Governments were merely complying with the spontaneous, nearly universal demands of a coalition of credential-havers and a plurality of lay public germaphobes: Codify lockdowns, or cease to have authority as government. “Flatten the curve” had suddenly been declared the way to “manage” the virus; everyone was already doing “flatten the curve;” if corporate didn’t suddenly issue a “flatten the curve” policy then it would have been revealed that no one’s actually “in charge” of this giant, global Target.

Neither China nor Zeynep Tufekci are responsible for insinuating lockdowns into Western consciousness and politics. China’s government is the government of China; and Zeynep was merely a prescient reader of the room in the West — too prescient, in fact, to get the credit for popularizing the meme, which fell to an obscure writer in the media backwater of New Zealand.

Lockdowns occurred because they gave scared, (literally) non-essential Western professionals “something to do.”

Authorities in reaction

As a forerunner of the “flatten the curve” panic, however, Zeynep does illustrate how central frustration with government “inaction” (in the face of media scare-mongering) was to the mindset that latched onto the phrase:

Absent any provenance in “authority” for “flattening the curve,” the concept had to be backfilled in scientific literature and nongovernmental organizations. Gates’s weforum.org essay calling for lockdowns is published on April 3. His advice for “what leaders can do” is skipping ring-round-the-rosie behind what the people being “led” decided to do. It’s not actually clear, however, if Gates’ advice is in fact in response to the embrace of lockdowns, as the word “flatten” does not appear — whereas Western governments of all sorts had already embraced it:

As an example of the uptake in a university administration, Michigan Medicine embraced the phrase even earlier, on March 11 — essentially the moment it went viral.

Author Kara Gavin (probably unintentionally) lies,

It's called "flattening the curve," a term that public health officials use all the time but that many Americans just heard for the first time this week.12

Again, if any references to flattening curves exists in published biological literature before March, 2020, it is elusive. The wikipedia page for “flattening the curve” is established as a redirect on March 12; content is not added until April 7.13

Almost the first reference to flattening curves in published scientific literature appears on May 27, in an article title “On the benefits of flattening the curve: A perspective.”14 As this is authored by two CDC employees and references the 2017 edition of the guidelines, it can be seen as the organization attempting to take credit after the fact for a strategy it was never bold or powerful enough to implement in the first place. There is little additional mention of the term until October, in a paper which is only relevant for being forced to cite lay reports from March, including the Michigan Medical post above, as provenance for the term.15

It would seem clear that the “authorities” are merely jumping on the bandwagon of the viral meme; and that the lack of what would be termed a “plan” (in the eyes of those in the professional class who imagined that some global response to the virus was in fact necessary) was diffuse throughout “authority”-dom before March 9, and not limited to the measured apathy of the Trump administration.

Only one organization seems to mount a truly agile reaction to “flatten the curve,” which is the Imperial College, who include it in the notorious intervention model spearheaded by Neil Ferguson and published on March 16; it also appears in a document by a quartet of associated modelers on the 9th.16

This publication (rather than Zeynep’s obscure article) is traditionally seen as the document more responsible than any other for prodding governments toward wild repression of citizens. Crucially, the Imperial College team of modelers can be counted among those who had taken up the task of mathematically fleshing out the CDC's 2007 graphic in the years between then and 2020; and Ferguson appears in 6 citations in the 2017 appendix.

I would posit, however, that the Imperial College may simply have been quicker than other institutions to perceive the importance of latching on to “flatten the curve” in order to preserve the imprint of authority in the eyes of the public, and their reward was a brief elevation to (an illusory) global influence. Someone was needed who would reattach the professional-worshiped, magical powers of “math” to the cartoon graphic which had taken over the world; Imperial College obliged. However, in at least this one case, perhaps a more suspicious interpretation is prudent.

Appendix:

This post is not meant to stand as my “argument” for any particular theory of the origin of lockdowns, nor does it claim to offer enough research for such an endeavor; nor does it seek to step on the toes of anyone else’s argument. As stated above, I have never found the idea that lockdowns emerged as a sort of mass psychosis in professional and social-media using classes as implausible or inconsistent with my own memory of 2020; nor do I think the “rudderless-ness” of Western administrations is instrumental to the question of whether there is an entity above those institutions which operates in conspiratorial manners. The compression of modern Western elite institutions into a single, global intellectual and political virtual salon would only render such an entity more unfettered, if not necessary, in wielding what is left of the state’s power and more importantly in influencing the media (which depends on access to the state for its own credentials to have any worth). Nor, finally, does this post seek to rule out that the “flatten the curve” meme was also artificially promoted in the media to any extent, either before February 27 or afterward.

If there is an “argument” for the origin of lockdowns in this post, it belongs to Kylstra.

If you derived value from this post, please drop a few coins in your fact-barista’s tip jar.

Senger, Michael P. “How Zeynep Tufekci and Jeremy Howard Masked America.” (2023, March 26.) The New Normal.

Tufekci, Zeynep. “Preparing for Coronavirus to Strike the U.S.” (2020, February 27.) Scientific American.

Tufekci, Zeynep. “It's the (Democracy-Poisoning) Golden Age of Free Speech.” (2018, January 16.) Wired.

Tufekci, Zeynep. “Why Telling People They Don’t Need Masks Backfired.” (2020, March 17.) The New York Times.

Wilson, Mark. “The story behind ‘flatten the curve,’ the defining chart of the coronavirus.” (2020, March 9.) Fast Company.

Quals, N. et al. “Community Mitigation Guidelines to Prevent Pandemic Influenza — United States, 2017.” MMWR Recomm Rep. 2017 Apr 21; 66(1): 1–32.

Chankova, Slavea. Pearce, Rosamund. “Covid-19 is now in 50 countries, and things will get worse.” (2020, February 29.) The Economist.

The byline is per the Fast Company recap. Despite the February 29 timestamp, the article appeared online on the 27th, and this is the date when it was read by Harris:

Roberts, Siobhan. “Flattening the Coronavirus Curve.” (2020, March 27.) The New York Times.

pp. 40-44. Community Mitigation Guidelines to Prevent Pandemic Influenza – United States, 2017 Technical Report 2: Supplemental Appendices 1-7 https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/44313

Kylstra, Carolyn “If You’re Waiting for Someone to Tell You What to Do, Here It Is.” (2020, March 14.) SELF.

Gavin, Kara. “Flattening the Curve for COVID-19: What Does It Mean and How Can You Help?” (2020, March 11.) michiganmedicine.org

Zang, F. Glasser, JW. Hill, AN. “On the benefits of flattening the curve: A perspective.” Math Biosci. 2020 Aug; 326: 108389.

Debecker, A. Modis, T. “Poorly known aspects of flattening the curve of COVID-19.” Technol Forecast Soc Change. 2021 Feb; 163: 120432. (online October 31, 2020)

Ferguson, NM, et al. “Impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to reduce COVID19 mortality and healthcare demand.” Imperial College London (16-03-2020).

Anderson, RM. Heesterbeek, H. Klinkenberg, D. Hillingsworth, TD. “How will country-based mitigation measures influence the course of the COVID-19 epidemic?” Lancet. 2020 Mar 21;395(10228):931-934.

Neither document offers a citation for “flatten the curve.” Anderson, et al. cite their previous document on “mitigation strategies” from 2011, in which the word “flatten” is not used.

there is a very simple answer to the origins of lockdowns, and everyone with some brain power knows it...

You're right it was a popular movement first. I remember explicitly "limiting my risk" based on the bs scare videos from China and all the rest of what appeared to be grassroots reporting, and the fact that China was obviously lying about the numbers.. I stopped using public transport and started working from home more. Now I wonder if that was actually all just an op. However, when facts on the ground in the US failed to match the supposed scenario in China.. when basically nothing happened, I figured it out: I didn't know why, or how, but this wasn't the sort of problem it was being billed as.

Unfortunately almost nobody else figured this out, and here we are.