American Awakening: Recalling the Holocaust

Transed and Nationless: The Post-Hitler West - Explaining the last three years as the diminishing cultural salience of the Holocaust, Pt 4.

Series notes

Comments on this series will be occasionally pruned for uninterestingness or evident failure to read and reply to the thesis itself. (Anything heavily centered on Jewish “machinations” in modern cultural and political affairs will probably merit removal on those grounds.)

Continued from part 1, which clarifies my position on Holocaust “Denialism” (I do not deny the Holocaust, but I insist that my understanding of what it was be based on normal historiographical standards, grounded in evidence and open to revisionism; anyone should do the same, the Holocaust should not be understood with a “special kind of history” the way children are given special scissors lest they harm themselves):

And part 2, which is an overview and introduction to the era of American history which will be discussed in this post:

(Also, obviously, part 3, which looks at the era of forgetting in detail, but only part 2 is strictly recommended as a preface for this segment.)

Disclaimer: “Holocaustianity” and originality

This part of the series depicts the rise of a cultural-religious phenomenon in America. Others have researched and written on this topic before, and the term which describes it pre-exists my work. While as a late-comer to this subject I expect to repeat many of the same points, it is nonetheless the case that unless cited otherwise, everything here was based on direct research of primary and secondary sources from before 1990 and is not a repackaging of someone else’s work.

1967-1980: Holocaust Remembered

The narrow stream shone strange and mysterious and two large winter birds flew along the surface, all the while screeching warnings, one to the other, not to get lost in the stormy twilight.1

At the turn of the 1980s, the Holocaust sat god-like in the pantheon of America’s spiritual, political, and media touchstones — a mere 14 years after the nightmarish epoch was still a forgotten and obscure footnote in history. What changed?

Old Testament: Jewish Spirituality and the Holocaust

1) “Doing our Jewish thing”

In the early and mid-1960s there are, as Jick mentions, developments that disturb the vacuum of Holocaust research and literature.2 But as these four-odd features - Raul Hilberg's long-delayed historical text, the Eichmann trial and Arendt’s Eichmann, Elie Wiesel's novels and media tours, and appropriation of the “holocaust” term - are in concert insufficient to ward off the unanimous lament of the Nuremberg journalists in late 1966 that the West has totally forgotten Nazi crimes, we may all but ignore them.3

If there is an obvious inflection toward mass awareness and attention, it seems to lie shortly after 1966, and at first to impress solely on the consciousness of America's (and Canada’s) Jews.

The Six-Day War is a widely-mentioned candidate, even if not definitive as the agent of change. With the dissolution of order over Israel’s borders in 1967, and consequent soft-denunciation of the Jewish religion and nation by the USSR, both the nascent Jewish homeland and Russian Jews were suddenly understood to be existentially threatened, and the Nazi Holocaust reemerged as a specter in the horizon. What might once have seemed an aberrant meteor described by folk-legend, became a fixed satellite haunting the Jewish race in modern life; who knew when it would rise again?

Further, it would hardly astonish modern readers if the cultural turmoil of the late 60s - sex, war, drugs, race riots, and rock and roll - spoiled the American Jewry's prevailing priorities of assimilation. With secular-Christian, middle class white America experiencing moral crisis, it would be natural for Jews in America (and Canada) to reassess their identity - to once again discover “being Jewish,” as a convenient exit from the demoralization of being white. Together, these factors precipitated a generational consciousness in which younger Jews would eventually be seen as a “new breed” deploring and dismantling the assimilationist project of their elders. According to a syndicated, precocious 1969 New York Times article:4

“Interest in Jewish Customs Increases, Leaders Report”

Spurred by a wide range of foreign and domestic developments — from Israel’s Six-Day War in 1967 to the Black Power movement — Jewish theologians and philosophers are showing a renewed interest in the recovery of traditional Jewish religious customs and teachings…

“Like others in today’s existentialist revolution, we are seeking not to assimilate with culture as a whole but to do our Jewish thing.”…

The passage of time and the continuing conflict in the Middle East have led Jewish theologians to confront two cataclysmic events in new ways; the Holocaust or Nazi destruction of six million Jews, and the existence of the State of Israel. … For many years the Nazi extermination of six million Jews was the subject of considerable documentation [citations, please] but little religious reflection.

“The Europeans who lived through it could not think about it objectively,” said Rabbi Seymour Siegel, a professor at the Jewish Theological Seminary in Manhattan, “It has taken a new generation simply to begin to confront it theologically.” … Articles and lectures on the Holocaust, however, have become frequent in recent years, especially since the 1967 war. “In the June War I saw the Holocaust as a psychological reality for the first time,” said Abie Pesses, a 22-year-old graduate student in Philosophy at the University of Toronto.

Notably, the backlash to the new breed's fixation on the Holocaust is, in this early year, already taking root among elder Jewish intelligentsia:

Others, however, disagree sharply. Rabbi David Hartman, a prominent 38-year-old Orthodox leader in Montreal, for instance, declared: “The Holocaust doesn’t fit in any place. It’s not a religious sign. It’s just a catastrophe.”

2) Holocaust awakening almost strictly Jewish at turn of the 70s

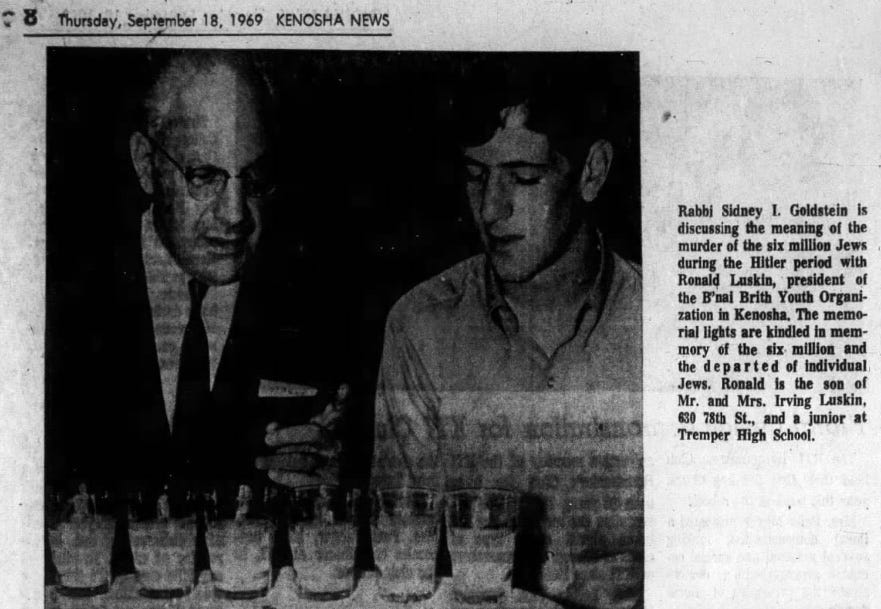

The renewed American interest in the Holocaust remains almost a strictly Jewish affair for several years. Two stories from 1972 convey the scene.

In one, “Jewish students originate course on Hitler ‘Holocaust,’”5 from The Boston Globe, it can be observed from the headline that the Hitler “Holocaust” is still not familiar enough to the presumed reader to be referenced without quotations (though, this is the latest example I have found).

Another feature of the story is that Hilberg’s 1961 magnum opus is still the only academic text dealing with the event (as previously noted, Reitlinger’s Final Solution from 1953 seems to be of little enduring impact). This, along with the unstructured nature of the curriculum and remarks of six lay visitors that “the experience constituted the most important day in their lives,” demonstrates that in 1972 the “study” of the Holocaust is still almost entirely “vulgarized,” as Philip Friedman put it in 1949, resembling less a historical science than a nascent philosophical or religious movement.

In the other example, “Young Jews probe roots of genocide,”6 the headline again affirms a primarily Jewish interest; in the accompanying text we learn that young Jews are “obsessed” with the Holocaust, and perceive the rather messianic status attained by Wiesel after his years of wandering the wilderness of American forgetting:

Jewish young people today are obsessed with a need to understand the holocaust of World War II that wiped out 6 million Jews, according to a man who blames their elders for letting it happen.

“On 80 per cent of the college campuses where I have been, the topic of the holocaust is more vital, more urgent, more compelling, than even the State of Israel,” said author and lecturer Elie Wiesel, a survivor of Auschwitz and Buchenwald whose novels deal with the experience of the Nazi death camps.[…]

“Most of my readers are young people,” Wiesel said. “Their parents come to my books through their children — it should be the other way around.”

For the young Jew in this country, he said, “the gate to the history of his people is through the holocaust. They want to know and their reasons are very deep.”

Continuing, Wiesel claims that interest extends to “religious” Protestant and Catholic students on campuses, suggesting that the phase of Christian Holocaust obsession is already beginning.

The Dawn of Holocaustianity

3) An immediately religious understanding

The above quote by Wiesel, and several others from preceding years, demonstrate that the author and lecturer understands the Holocaust in explicitly religious terms. It is a “gate to history;” and for Catholic students, “The more religious they are, the more interested they are.”

The year before, he sounds even more intoxicated with the religious implications of the Holocaust, essentially defining its meaning as a religion, and incredibly expressing a feeling of privilege for being able to “have known” the atrocity that left him orphaned and sister-less. From “Wiesel Makes Holocaust Meaningful to Youths” in the October 16, 1971 Religion section of the Philadelphia Inquirer:7

And for Wiesel, the Holocaust has come to represent a “mystical absolute” against which man must define what man is, what God is, what life is.”

“I don’t know what it was, but something happened that will affect generations to come—and our generation is privileged to have known it.” […]

Like others profoundly shaken by the Nazis’ “final solution to the Jewish question,” Wiesel keeps circling that “mystical absolute.”

The attempt to understand the Holocaust has been “cheapened” by putting it into a political context, he said. […] the motivation for the study should be “deeper — more profound. I might say ‘spiritual.’”

The work of defining what “man, God, and life” are is obviously and necessarily the work of a religion. The Holocaust, in this era of primarily Jewish but expanding gentile youth obsession, is obviously not just a means for reattaining a self-understanding of “being Jewish” - it is a way to make sense of all reality, material and spiritual alike. Here we may consult the definition that Jacob Neusner, later critic of America’s Holocaust obsession, offers for “myth” in the appendix of his essay collection on Jewish Identity, Stranger at Home:

Myth:

A story which tells the truth about how things are and how they came to be as they are; an account of the deepest meaning in the form of a tale or a narrative about sacred or holy events. This usage is standard in the study of religions and routine here. The use of myth in the sense of “lies about the gods,” and, by extension, lies in general, plays no role in this book.

This definition of myth aptly describes the relationship of the Holocaust to the young, white American mind in the early 1970s. It is not a lie, but neither is being true the essential or important quality of the Holocaust, rather than the truths it reveals. In this way the importance of the Holocaust lies not in truths of the past, but the truths of the present. Wiesel also perceives the importance of the contemporary world and its problems - the fall of the post-War Eden of a self-confident America and secure Israel - in infusing the Holocaust with significance, and in expressing this insight again flirts with trivializing the Holocaust itself:

“If I were a young person, I would be even more angry now. World problems are much deeper” than in 1945, when most people complacently felt that such a thing “would never happen again.”

But since then, he pointed out, a people was almost exterminated in Biafra; and Vietnam and East Pakistan have seen death and despair visited on millions.

“Of course, this is worse,” he said of the holocaust.

Wiesel’s insight is instructive for explaining the appeal of the Holocaust to secular-Christian youth; indeed we can from simple assessment of the facts ascertain that expansion of the obsession to all of white American society was inevitable. If Jewish youth found in the Holocaust mythos a relief from the anxieties and angst of American turmoil, surely the same psychological needs were operating, unsatisfied, and just as intensely if not more-so, among secular-Christian youth: They, too, needed to find religion - to discover a myth that could make sense of “man, God, and life.”

4) The Great Redemption of the West

Despite Wiesel’s raptures, it might still strike the reader as difficult to accept the over-simplified, but also peculiarly sacred “Comic-Book” version of the Holocaust which emerged in the collective consciousness after the 1960s as a religious myth.

If so, this is only because the religion has been confused for a standard facet of the secular cultural and media landscape for so long that the profound wisdoms and moral guidance conferred by the Holocaust can be taken for granted. It must seem that surely we would all understand the world just as well — you could say “accurately,” “richly,” or “functionally,” with a great deal of overlap in all three terms — surely we would all get by without it. But we wouldn’t; we would be lost; or at least more of us would be lost, or more lost than we are. The Holocaust is how, from childhood, secular Americans train the soul to comprehend (and attain the failure to comprehend) the most profound questions of existence, in a society that mocks and pathologizes worship of God.

Thus to perceive what the Holocaust is to the modern, secular-Christian American psychology, we must study the reactions of those who met the myth as teens and adults living in a fallen and senseless world, the “Godless heathens” converted by revelation.

The following quotes will largely speak for themselves, but I will offer two remarks beforehand: Firstly, Philadelphia seems to be the new religion’s Graceland, and is where many of the materials that help franchise “Holocaust courses” to public schools are developed, as well as the earliest seminars given. And a now-scarcely-remembered Protestant Professor at Philadelphia’s Temple University, Franklin H. Littell, is largely responsible for the early work of decoding and articulating the Holocaust for a particularly Christian psychology, and as such may be regarded as a sort of modern American prophet (as could Wiesel, of course).8 Littell’s work is remembered at Temple and his role in transforming Christian understanding of the Holocaust is acknowledged by Holocaust scholars, but this recognition does not match the likely scale of his impact on American society (and the West) at large.

Newspaper quotes from the secular-Christian discovery of the Holocaust

1974

And then the larger questions: How could the Holocaust have happened? How could the world have remained silent in the face of Nazi atrocities? How shall we think of God after the Holocaust? Is there a meaning behind the Holocaust? Can it happen again? […]

“If some of these questions remain unanswerable, students nevertheless see them as significant. They have also seen that the Holocaust is more than horrors, agonies, and sometimes unanswerable questions. Through their readings and visits by survivors, they have glimpsed something of the miracle of survival, of man’s extraordinary resilience and endurance, his capacity for humanity under the worst conditions, and his capacity for spiritual resistance […] they are gaining a deeper awareness that barbarity is not the whole truth about man.”

—15 Marist Students Studying Literature of Nazi Holocaust, Poughkeepsie Journal

1975

The Christian Church has lost its credibility and, basically, will have nothing of importance to say to the world until it reestablishes its brotherhood with the Jews, asserts one of the nation’s most prominent church historians.

Prof. Franklin H. Littell, of Temple University, said during several gatherings here last week that until the church faces up to the Holocaust which cost the lives of 6 million Jews in Germany, it might as well shut up about other moral issues. […] Littell stressed the point even more forcefully in a new book, “The Crucifixion of the Jews” […]

Littell’s contention is, then, that in forgetting about the Holocaust, the Christians are deliberately cutting themselves off from the source of their faith and, thereby, becoming an “apostate” church.

—Christians Owe Moral Debt to Jews, Wisconsin State Journal

In the agony of the Holocaust, victims and others upon whom horror and tortured deaths are inflicted in our modern world, Christ is crucified.

—The Crucifixion and the Holocaust, Suffolk Newsday

1976

A generation has passed since Auschwitz and Dachau, a generation that chose to be silent and spare its children the horrors of those names.

Now the children want to know.

“It takes a long time for the pain and the guilt to subside,” said Franklin Littell, chairman of Temple University’s religion department. “Now we are ready to study what happened in the concentration camps of World War II, and students are ready to hear the story and learn what it means to civilization.” […]

[Michael M. Ryan, a lay professor at Drew University] calls the subject “the most important lesson for humanity.”

The course, he says, stresses the actions of Christians in World War II. The Holocaust, he believes, was not the result of Germans or Nazis, or even Hitler, as much it was the failure of Christianity and civilized society.

“I feel, and my students understand, that no one can lay claim to the good points of Christianity without facing the Holocaust,” Ryan said. […]

Already, about 65 Philadelphia public school teachers have attended seminars on teaching about the Holocaust. The center, with the cooperation of the school district, has designed a teaching manual that is expected to expedite setting up courses and course segments by next fall […]

[M]ost of the [new Holocaust] courses are taught in religion departments […]

—Holocaust, Columbus Ledger-Enquirer

1977

(Here, we encounter the article prompted by ADL director Theodore Freedman’s educational lobbying. Regardless of whether Freedman’s activities were motivated by notions of garnering widespread concern for Israel after the Six Day and Yom Kippur Wars, it would seem clear that he is latching on to a Christian spiritual awakening that required no additional Jewish influence after 1975. Additionally, Freedman is clearly more clumsy than Wiesel or Littell in articulating the religious significance of the Holocaust.)

Freedman said the general objective of the Holocaust studies is “to make our young people better adults and better cope in a complex world.”

“Sometimes examining history can be a very painful thing — seeing both the worst human behavior and the very best in human behavior,” he said […]

“It’s an essential part of the survival of all people to understand the meaning of the Holocaust,”[…]

[Charles Speiker, school district director who attended an ADL-sponsored conference on Holocaust courses in New York City] said he has no illusions that the schools can solve social problems (such as prejudice), but they can plant “some seeds of hope.”

Regarding the above quotations, it should be noted that they were not produced by anything like a thorough exploration of the era. These are all from the first articles I retrieved - the explicitly religious or mystically “sense-making” dimension of the Holocaust in the 70s-era secular-Christian mindset is mentioned in every case.

Three years after the last of those quotes, secular-Christian Americans have embraced the Holocaust so vigorously that within the community of Jewish elders - some skeptical of the Holocaust’s relevance to the living Jewish experience from the very beginning - a chorus of critics have formed to lament the “commercialization” of the “Holocaust industry,” prompting the New York Times article quoted in the introduction to this segment (Pt 2). Even Wiesel, for whom the mystic catastrophe had so recently been irrepressible and eternal, has turned cold.

Wiesel, a Holocaust survivor, and author of several books on the subject, recently said: “In the beginning, nobody did, so I had to speak. Now everybody does, so I don’t want to speak.” […]

Why, Professor Neusner asks, “do [today’s Jews] draw upon experiences they have not had and do not wish to have for their symbols and their myths, for their rites and their deeds?9

The elders’ protest may have come too late. Like the converted gentile, a generation of Jewish children, for better or worse, had already been raised to understand the world through the lens of wholesale persecution and nightmarish executions.

The Twilight of Holocaustianity

5) The Anglosphere’s Sense-Makers

One other clue to the inevitability of 1970s secular-Christian America’s embrace of the nascent Jewish Holocaust Religion, is that Western gentiles seem incapable of creating their own myths.

It is a popular antisemitic trope to posit, in one form or another, that Jews control what society at large is allowed to think, know, and say, and as proof it is offered that many of the highest posts in Hollywood and other media realms are occupied by Jews.

But until it can be demonstrated otherwise, it is perhaps better to suppose that this is simply because we non-Jews of the English, Protestant cultural lineage typically have no idea how to tell ourselves stories that make sense of the world. I wish to emphasize this element of the Holocaust mythos here, because it will invite contemplation, in the final segment of this series, of what it means for the now largely-Anglicized West to move on from understanding itself through the Holocaust.

Having little familiarity with broader European cultural traditions, I do not purport to suggest any special relationship between Jews and all non-Jews. But the special need the English-speaking gentile bears for culturally alien myths seems to be a historical theme, and Jews have long been the most durable source of culturally alien stock in the English-speaking world. Reading Arendt’s Origins of Totalitarianism, I was struck by a quote of Benjamin Disraeli (who, being born to a culturally assimilated Jewish household, invented his own ostentatious and arrogant mode of “being Jewish” in English society, and won fervent celebrity status among British elites as a result). It is from Lord George Bentinck, and reads in full (emphasis added):

[W]e hold that instead of being an object of aversion, [the Hebrew] should receive all that honour and favour from the northern and western races, which, in civilized and refined nations, should be the lot of those who charm the public taste and elevate the public feeling. We hesitate not to say that there is no race at this present, and following in this only the example of a long period, that so much delights, and fascinates, and elevates, and ennobles Europe, as the Jewish.

It is a fitting irony that Christian Holocaustianity in the 1970s is derived from Jewish Holocaustianity, and that the Christian form seems more passionate and the Jewish more practical; but it is not merely an irony. It seems to speak to a certain destiny, one that has guided the West to its dominance over cultures not similarly gifted with Jewish sense-making.

Jews and European non-Jews would seem like the two birds so vividly portrayed by Singer’s fictional visit to a Polish river resort, “screeching warnings, one to the other, not to get lost in the stormy twilight;” and for half a century the Holocaust has been the central myth keeping the secular West from losing its way in the storms of imperial decadence and decline.

Who screams warnings to the West now?

Next in the series:

Reflections on a gilded age

Series notes Comments on this series will be occasionally pruned for uninterestingness or evident failure to read and reply to the thesis itself. (Anything heavily centered on Jewish “machinations” in modern cultural and political affairs will probably merit removal on those grounds.)

Also:

Part 1: Introduction; RE Holocaust “Denialism” ↗

Part 2: Introduction to the forgetting and rediscovery of the Holocaust ↗

Part 3: 1945-1967: The forgetting of the Holocaust ↗

Part 6: The need for new sacrifices 2017-pres. ↗

Bashevis Singer, Isaac. Shosha. Goodreads Press.

Jick, Leon A. “The Holocaust: Its Use and Abuse Within the American Public”, Yad Vashem Studies, vol. 14 (Jerusalem, 1981) At nli.org.il

Jick gives treatment to the developments of the 60s which I have glossed over.

It can however be remarked that Jewish Holocaust remembrance became a niche occupation by 1966, and that “Denialism” was an animate force in the radical right (including neo-Nazi parties in Germany and the US), with debate on the 6 million death figure spilling into newspaper pages, see “Letter: Allied War Crimes Commission Authority for Estimate of Murders Committed by Nazis.” The Montreal Star. (Jun 20, 1966.) At newspapers.com

Fiske, Edward B. “Scholars Seek New Meaning in Jewish Tradition.” St. Louis Jewish Light. (Dec 3, 1969.) Reprinted from The New York Times. At newspapers.com

For a later assessment of the youth backlash against assimilation, which includes the “new breed” terminology:

Zuckoff, Murray. “Labels Newsweek Study of Jews As ‘Factual’ But Not ‘Actual.’” St. Louis Jewish Light. (April 7, 1971.) p 7. At newspapers.com

[A]n essential element that is revolutionizing Jewish life in America: the rising tide of Jewish national consciousness among a growing segment of Jewish youth, a segment referred to quite frequently within the Jewish community as the “new breed.”[…]

The Newsweek study failed to deal with or analyze this development which is taking the form of a struggle for Jewish liberation from the assimilationist mentality pervasive in the “older generation.”

Shapiro, Leo. “Jewish students originate course on Hitler ‘Holocaust.’” The Boston Globe. (Dec 25, 1972.) At newspapers.com

“Young Jews probe roots of genocide.” Arizona Republic. (Nov 09, 1972.) Syndicated from Washington Post Service. At newspapers.com

Wallace, Andrew. “Wiesel Makes Holocaust Meaningful to Youths.” Philadelphia Inquirer. (Oct 16, 1971.) At newspapers.com

Littell’s interest and scholarly work on the Holocaust span all of the years after 1939, when he witnessed a Nazi rally at Nuremberg. However, it seems to require the problems of the 1960s and 1970s for his understanding of the Holocaust to take on such magnificently Christian themes. At all events it is to be noted that he was not merely taking on the Holocaust in response to the renaissance of Jewish interest and discussion.

Jacob Neusner, quoted in Hyman, Paula E. “New Debate on Holocaust: Has Popularization of the Tragedy Diminished Its Meaning and Diminished Other Aspects of Judaism?” St. Louis Jewish Light. (November 19, 1980.) (Syndicated from New York Times.) At newspapers.com

"should not be understood with a “special kind of history” "

Wouldn't that be nice.

A German mainstream politician recently suggested that "climate denialism" should be criminalized similar to how "Holocaust denialism" already is. (e.g. you can go to prison for arguing it was really 5.7 million, not 6.0+)

Great article as usual; while doing some google-fu I came across an essay that focuses on the changing meanings of the word:

'The secular word HOLOCAUST: scholarly myths, history, and 20th century meanings'

https://www.armenews.com/IMG/pdf/arc_petrie_the_secular_word_holocaust.pdf

A thought that came to mind is that history is not so much the writings of the victors, than a narrative formed by the elites. (and begs an explainer for the motivations of such choices...)