Against Techno - Whateverism

Numbers do not outperform experience when discerning quality of life

A wishifesto

Marc Andreessen authored the first popular web browser, a long time ago, shortly after Al Gore invented the internet. Although not going on to become a household name, he managed to build a substantial tech business footprint, as well as a tech media footprint of some extent which I won’t attempt to quantify, since I spend no time in that ecosystem. But I’ve wound up subscribed to his new substack as of earlier this year, and coincidentally have encountered his freshly-published “manifesto” on techno-optimism. Like his other work, it is largely a Steven Pinker-esque admonition that all present cultural and economic anxieties in the West are so much ninnyish fretting in ignorance of the really good metrics being racked up in Earth’s global report-card.

Since Unglossed is in part a critique of the modern cultural myth of Science, or scientific magic — of a special process of human activity immune to the obvious epistemic limitations of Not-Science so long as it, Science, preserves the performative trappings of Science, and therefore capable of delivering special insights and developments about and into the world, by virtue of said trappings, rituals, and documentations — a “techno-optimist manifesto” certainly invites comment. However, I feel it would risk abusing the reader’s time to be too thorough; and so I won’t be.

On progress and expertise

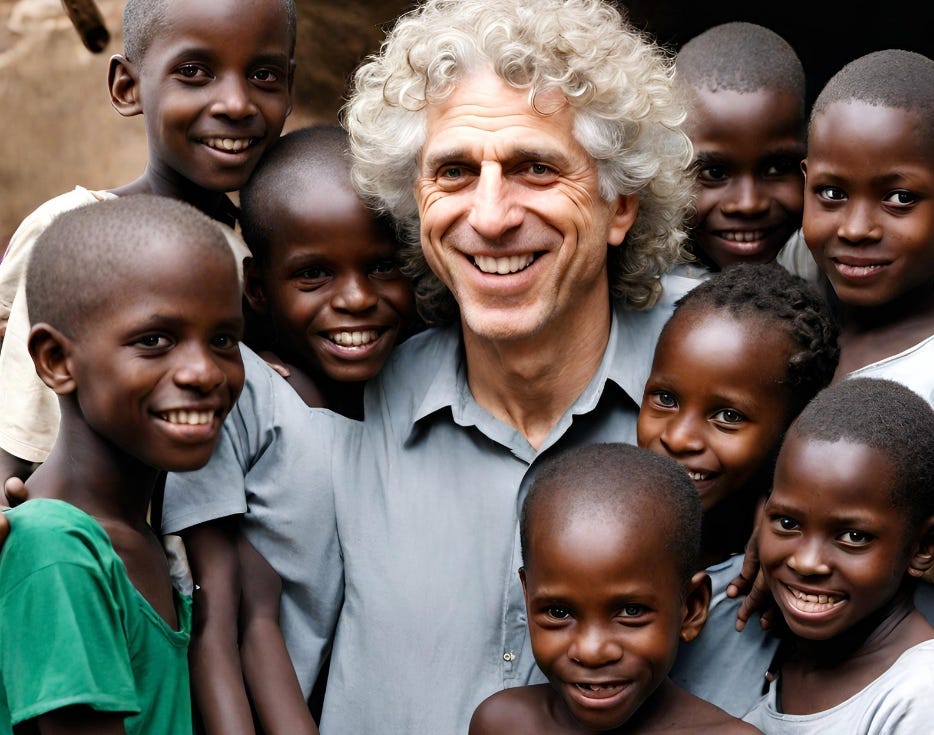

We start with Pinker — seen below alerting several African children that he has found Earth’s Goodness Numbers to have increased by another 12,000,000,000,000,005 units since breakfast. In his books Better Angels and Enlightenment Now, Pinker argues that violence is diminishing and material standards and well-being are expanding globally, regardless of lay perceptions to the contrary. Progress is being made.

The Techno-Optimist Manifesto (TOM) recycles this argument: The first section names “lies” regarding the ills of technology; the second section delivers “truth” to counter it. This truth is even more clearly stated in the following section, “technology”:

We believe that there is no material problem – whether created by nature or by technology – that cannot be solved with more technology.

There is something laudable in both Pinker and Andreessen’s questioning of narrative memes that have poisoned naturalistic interpretations of material conditions. It is a correction to our individually and collectively neurotic tendency to “discount the positives” — to remove goods from the ledger of our present situations by presuming all goods categorically to be granted, and so to take them for granted, leaving only an endless focus on whatever ills remain.

For this reason, many of the social organs Andreessen names as the “enemies” of techno-optimism also can be considered enemies of individual and collective determinism. By this, I mean the suppressed prerogative of citizens in expertocratic, media-dominated societies to discern the world as they would see fit, define or defend their own values, and think freely. Andreessen is right that there is a “demoralization campaign,” authored by a “know-it-all credentialed expert worldview, indulging in abstract theories, luxury beliefs, social engineering […] playing God with everyone else’s lives, with total insulation from the consequences.” This aptly describes the cause of the disaster of the so-called pandemic and the debacle of the vaccines.

But here we can already spot tension in Andreessen’s vision of reality, as he has earlier said:

We had a problem of pandemics, so we invented vaccines.

The statement itself depends on and takes as valid the authority of know-it-all credentialed experts playing God with everyone else’s lives. The very definition of “pandemics” as a solvable problem is the manufacturing of a need for expert intrusion into whatever people would do otherwise, and of a guaranteed outcome in which whatever prevails after expert intervention will be declared a success. Andreessen might seem to not include such interventions — perhaps, to be proposing some laissez faire situation in which vaccines are privately created and privately distributed — but would that “solve” the “problem” of any given pandemic? What if no companies wished to risk liability without state exemption — exactly what actually prevails in the vaccine market? What if substantial portions of the population, reasonably, do not consider the “pandemic” to be enough of a risk to justify an unproven vaccine?

The “technology” of vaccines cannot solve these secondary problems; in fact it creates them.

Thus we have in this example — though of course there are others — uncovered a fundamental problem with techno-optimism. Yes, the overall “demoralization campaign” against technology could do with a bit of criticism, but the “truth” is still ultimately, actually, that technology can create problems. Vaccines create problems from an ethical standpoint even under the most optimistic assumptions. Presuming only 1 person to die via a vaccine “reaction” in an entire world-wide vaccination campaign, vs. 1,000,000,000 deaths averted, merely leaves us at the trolly problem; no answer will ultimately be consistent with any moral system besides explicit utilitarianism, with no convention of individual right to life (exactly why shouldn’t the billion be neatly culled by the virus, so that the one not be ostentatiously slayed by the cure?). The “solution” to this problem in practice is merely to let experts tell us there is no problem (no matter how far the reality is from the very optimistic example just used). Andreessen’s eliding of the problem is itself a luxury belief sustained by expert know-it-alls.

From this it would seem that Andreessen’s “enemy” isn’t expert know-it-alls per se, but merely those who propose that technology is creating problems for humanity, or even worse, propose state intervention to address the same. What is seemingly envisioned is a world-order in which the virtue of technology is not only widely-appreciated and celebrated, but unquestionable. Debate prohibited. Put differently, we have uncovered a way in which Andreessen himself is discounting a positive, and taking for granted an element of technological “good” that is totally dependent on the top-down authority and dogma he wishes to attack.

In a weaker sense, the entire notion of defining human progress and flourishing by material metrics dooms society to expertocracy. How else will Pinker’s “Enlightenment Now” continue to be validated, if the authority and accuracy of the experts and their statistics is discredited? Why should the lay reader therefore trust the expert’s raw numbers but not their wholistic conclusions — especially if the former are directly in contradiction to individual perception, as for example is the case with our present inflation statistics? Pinker and Andreessen are ultimately seeking to alter the results of the default modern Western epistemology — reality as a set of curated statistics produced by experts — without making any changes to the epistemology itself.

On momentum and externalities

The flaw of some problems created by technology being unsolvable (without expertocracy and state intervention, as is the case with vaccines) is a subtler echo of the explicitly-acknowledged need for more technology to solve problems created by technology. We can spot such needs easily in many of Andreessen’s other “solutions.” To give two examples:

We had a problem of starvation, so we invented the Green Revolution.

We had a problem of isolation, so we invented the Internet.

The Green Revolution has given us (and the world at large) the problems of rampant diabetes, obesity, environmental hormonal poisoning, increased pollution (starved and dead people cannot pollute), and more. The Internet — where does one even begin. And both these “solutions” together contribute to the current migration crisis, which can be summarized as the global south voting with its feet that Pinker and Andreessen’s technological progress isn’t arriving nearly fast enough to dissuade the people of the developing world from simply trading places with the West.

Again, this paradox is explicitly acknowledged — the techno-optimists believe that problems created by nature or technology can all alike be solved by more technology.

Except, do they? Why for example, then, cannot more technology (if applied now) solve the problem of having restrained from more technology due to prior “demoralization campaigns”? Andreessen is dire on the energy situation when it comes to the lost opportunity of nuclear power:

Our enemy is the Precautionary Principle, which would have prevented virtually all progress since man first harnessed fire. The Precautionary Principle was invented to prevent the large-scale deployment of civilian nuclear power, perhaps the most catastrophic mistake in Western society in my lifetime.

Why, in other words, couldn’t and can’t the “problem” of reduced nuclear plants be solved by technology? If technology can axiomatically solve any problem created by technology, it should also be able to solve any problem created by the arbitrary proscription of any one specific solution. There is no intrinsic principle that can render one true while the other is false. But wind, solar, everything else — they are failures. Fusion is a hypothetical at best — it doesn’t prove an alternative, contra claims made in the “Energy” section. If the problem of energy is unsolvable without nuclear, then unsolvable problems can exist, and there is no reason why they cannot include problems created by technology.

The very conception of technology offered by the techno-optimists — namely, a limitless miracle-worker upheld by faith — is a fantasy without rational basis.

At best, it is an extrapolation from present trends into the future without any particular justification. Why should the trend of some technological problems being solved by other technologies continue forever, as opposed to any particular prior trends in history, which one after the other have ended? The implicit answer is “because technology” — the techno-optimist takes it on faith that “technology” is a cosmic force subject to laws that govern its properties and capabilities, as opposed to an accident of human discoveries and developments. The opposite view, that of Spengler, that there is a pre-determined limit to development defined by cultural thought and material possibility, isn’t seriously considered.

Likewise, the techno-optimist manifesto doesn’t propose any serious answer to the default position that some technological problems probably will not be solved by more technology.

Regarding environmental degradation, for example, consider the claims made in the section called “Energy” (emphasis in original):

We believe energy should be in an upward spiral. Energy is the foundational engine of our civilization. The more energy we have, the more people we can have, and the better everyone’s lives can be. We should raise everyone to the energy consumption level we have, then increase our energy 1,000x, then raise everyone else’s energy 1,000x as well. […]

We believe technology is the solution to environmental degradation and crisis. A technologically advanced society improves the natural environment, a technologically stagnant society ruins it. If you want to see environmental devastation, visit a former Communist country. The socialist USSR was far worse for the natural environment than the capitalist US. Google the Aral Sea.

There are several logical problems here. “Improving” the natural environment requires that it is first degraded by technology; and, unless “improving” totally nullifies that degradation, all that is really described is “amelioration” of the technological problem of environmental destruction, not “solving” as promised in section 3. The “enemy” — the default pessimistic outlook on technology — wins the case. All Andreessen can do is therefore point to even worse examples under worse economic contexts. But the standard for “solving” the problem of environmental degradation is implacable — it is not simply accepting whatever partial amelioration we have managed to date, because it could be even worse, but actually restoring nature.

Further, what is supposed to happen if we, at our current level of the technological problem of environmental degradation, increase our energy use a thousand-fold? Shouldn’t we expect a thousand times our current degradation? Isn’t this at best an argument for stopping at “raising everyone to the level we have” — with the problem ameliorated everywhere, but not solved anywhere?

Finally, on employment, where Andreessen is particularly optimistic, technology is given credit it does not deserve. What followed the advent of electricity and subsequent introduction of energy into human work was a global breakdown of employment markets — the Great Depression. The economic transformations which have followed WWII — including the transformation of the US government into a corporate welfare subscription service, and the massive expansion of government-funded healthcare and corresponding jobs — proscribe concluding that the subsequent era of low unemployment was primarily technology-driven1, or that future technologies will magically not cause unemployment. At best one could argue, “let’s wait and see.”

On number worship and the meaning of life

A deficit of the post-War liberal, Americanized mindset is to self-alienate from raw, subjective appraisal of the human experience. Individual and consensus expressions of belief about what is real are worth nothing compared to putatively well-compiled statistics.

To take an extreme example, one might imagine that some magic device inflicts severe depression on everyone on Earth, while simultaneously providing for material needs. Is this good or bad? According to The Numbers, it is good — the best actually, if you compare it to before, when The Numbers were lower and less good.

And actually this isn’t an “extreme example” at all — it is precisely what any purely subjective complaint about material progress comes down to. Only, by crafting the thought experiment so as to demand universal severe depression, we have made it impossible to dismiss the same outcome as just some imaginary figment nursed by misinformed discontents.

Litigating whether Numbers Good or Feelings Bad is a better reflection of reality is difficult. For one thing, both must start by explaining who is asking, and whose numbers and feelings the asker should care about. In most political contexts, the material advancement of the developing world has absolutely no bearing on whether Americans (for example) are content with the standard of living that derives from work (or with the type of work that now constitutes “work”), all realities and possibilities influenced by technological development. But likewise, meta-narratives about changing quality of life often only have purchase and relevance in a narrow subset of the population, with most people being too indifferent or distracted to join the debate — and these people, i.e. the majority, may be totally content with things as they are. Neither approach can reliably deliver the truth because neither offers a definitive answer to “the truth about what?”

Here, the techno-optimist manifesto attempts to provide an answer; a justification for why increased material abundance imbues technological development with a value that extends beyond naked utilitarianism (which would obviously obviate individual rights) — and reveals a fundamental ignorance of the spectrum of possible human experience. This justification appears in the section “The Meaning of Life”:

Techno-Optimism is a material philosophy, not a political philosophy […]

We are materially focused, for a reason – to open the aperture on how we may choose to live amid material abundance.

A common critique of technology is that it removes choice from our lives as machines make decisions for us. This is undoubtedly true, yet more than offset by the freedom to create our lives that flows from the material abundance created by our use of machines.

Material abundance from markets and technology opens the space for religion, for politics, and for choices of how to live, socially and individually.

We believe technology is liberatory. Liberatory of human potential. Liberatory of the human soul, the human spirit. Expanding what it can mean to be free, to be fulfilled, to be alive.

We believe technology opens the space of what it can mean to be human.

How can anyone seriously claim that technology “opens the space of what it can mean to be human”? Technology, like liberalism broadly, has abolished all real “choice” in human experience by limiting the same to whatever can (and would) be chosen. What is excluded most overtly, absolutely, is the sincere and natural human belief that the world is miraculous, that human affairs including birth, sickness, and death reflect divine technologies. Material technology has all but ruled this out as a possible human reality; Andreessen no doubt considers it not even worth tallying (his “religion,” whatever he means by it, is not religion); but it obviously represents a greater difference in “how to live” than any that can be chosen in a materialistic society.

This narrowness of conception of “human potential” is not new; it does not begin with Andreessen, but is the defining blindness of post-War American liberalism. By another coincidence, I have just read Allan Bloom’s critique of Rawls’ Theory of Justice2; the same limitedness of conception is clear (and Rawls is nothing if not a prefigurement of Pinker and therefore any similar thought). Emphasis added:

This becomes clear in Rawls’s discussion of what he calls the primary goods. The notion “primary good” plays the same role in Rawls's teaching as does “power” in Hobbes’s, and Rawls’s list of primary goods is similar to Hobbes’s list of powers.

But for Hobbes powers are not simply neutral. They depend on ends, and there are some ends or life plans for which all [Rawls’] listed primary goods would be evils.

What is wealth for him who believes that it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter into the kingdom of heaven? What is health for him who believes with Pascal that sickness is the true state of the Christian? And how does the sense of one’s own worth, rather than humility, accord with the man who believes he is a sinner? To treat these things as goods is equivalent to denying that view of things in which they are the opposite.

And Hobbes does deny the validity of the opinions which are incompatible with the powers on his list. Rawls avoids denying such opinions by not paying attention to them. He only takes seriously opinions which fit the society he proposes.

Technology and liberalism — civil order not based on aristocracy and revelation — constrained the spectrum of human experience so entirely that all naturally non-materialist value-systems became impossible; they were purged from Western society. All that remained were harmless non-materialist “lifestyles,” and this includes religion and church-going as most people in the West after the 1600s have understood it (with exceptions for various American sects after the first Awakening; and whereas you still see revelation in Russian literature for long afterward).

Andreessen, like Rawls, implies by inattention that such “human potentials” aren’t worthy of the name. The aperture expands into some new potentials; so what, really, about the ones upon which it closes? He acknowledges only that machines might impinge on our allotments of “decisions” — confessing an inability to conceive of a mode of existence in which deciding itself is unthinkable, and life has goods that supersede preservation of life and the curation of harmless sensations. This is to say nothing of the opposite end of the spectrum, the “human potential” of the warrior and plunderer — for if technology in fact can preserve this “human potential,” it must be at the expense of overall “human potential” as a materialist would describe it. But Andreessen’s manifesto doesn’t mention anything about AKs, urban guerrilla warfare, piracy. More moderately, how are we to value the extreme dislocation from (material and spiritual) nature wrought by technology? Are we simply to be happy about the fact that it is no longer really possible, for most people, to grow up in the wild?

The course that must be taken is to preen and parade the trivial spectrum of choices that remain. Certainly, viewed in comparison to the palette available to, say, the 1950s American middle class, “the internet” offers more cultural diversity. But even here the tradeoff is unmistakable: Nowhere on the menu of current cultural “choices” is a monoculture with entrenched privileges, strict immigration laws, widespread healthy body-weight, etc. But more to the point, when compared with the true “freedom” to experience super-materialist modes of existence, previously the (non-optional) birthright of all of humanity, the only thing that can justify the narrow concession-stand choices which remain is a disdainful confidence that all those other lost potentials, so much more vast and deep in scope of diversity, were simply “bad.”

Bloom writes that for Rawls,

The kind of diversity he thinks of is that found in obscure but harmless religious sects or in obscure but harmless sexual practices. The kind of diversity which produces great actions, great art, or great new civilizations is out of his reach. He provides a soil which is not salubrious for the growth of a diversity that is worthy of the name. The solid thing is survival; in a world where the great value decisions are akin to the choice between vacationing in Paris or Rome, where they cannot change the fundamental character of civil society, there is no reason for difference.

Is such a limited possibility of experience really fit to be described as the “meaning of life”? And if so, why do such droves of modern youths reject it outright?

If you derived value from this post, please drop a few coins in your fact-barista’s tip jar.

Except of course in the sense that medicine has exponentially increased the amount of care that can be delivered to an individual before they are allowed to die.

Superb piece.

Very nice Brian. Perhaps the flaws of techno-optimism can best be summed up by saying that it simply begs all of the questions of humanity.

I have been reading Chesterton on Distributism lately, but really anything from more than 100 years ago will do, and it is just startling how much our range, our options have decreased. We are not simply able to do fewer things but we are able to think fewer thoughts, although we can perhaps go deeper down into the hole that we have dug ourselves than our ancestors could the breadth and range that are available to us are so far contracted. And these jackasses don't even realise it.