Polio series table of contents:

The following is Pt. 2 of “The Polio Problem.” As previously outlined, it will deal in serial fashion with various “simple solutions” to the enigma of polio that fail, often in stark fashion, to match the evidence.

The conclusion that must finally be reached — that what caused the emergence of polio epidemics was a change, somehow, in human susceptibility — requires understanding why no other answers explain the problem. Then one can see the mystery of polio as the mystery of why humans suddenly were susceptible to the virus as never before.

Still, for most topics this post will keep the discussion as streamlined as possible.

A more thorough discussion of the question of “misdiagnosis” was presented in Pt. 1; and a separate series is presently dealing with the enormity of flaws in the “toxin theory” of polio. This post and a follow-up takes on what is left-over.

It wasn’t genetic susceptibility.

It wasn’t hygiene.

It wasn’t transportation.

In Pt. 3, or in an update to this post, depending on my whim:

It wasn’t imagination / over-reporting.

Was it all medical intervention (in response to fear of the disease itself)?

Was it a change in the virus?

Note: Some citations are missing at the time of publication, and will be added in an update.

It wasn’t genetic susceptibility

If epidemic polio paralysis were simply an eternal, ancient human disease, held off at present only by vaccines, the first explanation modern scientific thought would propose for “why are some individuals susceptible, when most people are hunky-dory” is obvious: Muh genetics.

Genetics, despite such little progress today compared to the fantastic expectations of the 1990s, remains the means of first resort for biology to explain any end.

The 2019 paper quoted at the head of the previous post, which acknowledged that “the pathogenesis of neuronal infection and paralysis in only a minority of patients” remains “unanswered”1 — what explanation did it set out to explore, in hopes of finally solving the riddle? Of course: genetics.

Poliovirus is one of the most studied viruses. Despite efforts to understand PV infection within the host, fundamental questions remain unanswered. These include the mechanisms determining the progression to viremia, the pathogenesis of neuronal infection and paralysis in only a minority of patients. Because of the rare disease phenotype of paralytic poliomyelitis, we hypothesize that a genetic etiology may contribute to the disease course and outcome.

Spoiler: It found no patterns in “genetics” to explain anything. Polio patient immune cells seemed just as able, if not a bit more, to mount an antiviral response than controls.

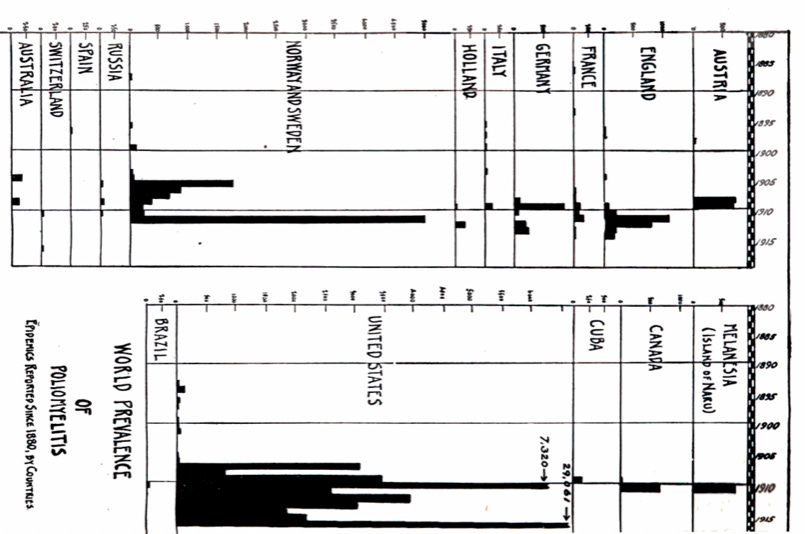

But of course genetics is not the answer. Polio is not an eternal, ancient disease. If we set aside the amnesia of modern scientific research, and remember how polio epidemics emerged, out of the blue as it were, there is no real chance that humans in Europe and far-flung settlements in Australia and the United States (already a hodgepodge of European immigrants) suddenly all developed some novel gene defect at the same time. Nor why they were (in evolutionary terms) followed “overnight” by Japanese, Israeli Jews, myriad islanders, and, eventually, every race in the world.

Conclusion: Genetics cannot explain the emergence of polio epidemics. If Europeans as a whole were really genetically susceptible to polio, epidemics would have been a constant feature of history in Europe.

This leaves the question of a change in the virus, which is more interesting — but will be discussed last, because it isn’t as easy to dismiss.

It wasn’t hygiene

Modern readers may have encountered the hygiene hypothesis in connection with the polio enigma — or vice versa, have heard polio used as an example for the hypothesis. It seems promising: Polio was a globally ubiquitous childhood virus; it turned out to exist everywhere already; but only “countries with modern sanitation” suddenly started to experience paralysis.

My own memory of the lay understanding of the theory (from before researching the topic directly) is a trope that American Blacks were rarely affected by polio — it was a disease of middle-class whites. Suffice it to say that this was not true: Whenever Blacks lived in the same areas where whites were being affected heavily by polio (as opposed to the south, before the 1940s), they also experienced epidemic polio paralysis. Two urban outbreaks from the first years of the Salk vaccine — this is the same time that statistics on the disease were the most thorough, and also after the Great Migration had made such side-by-side urban comparisons more common — in Chicago2 and Baltimore3, featured starkly higher rates of cases among Blacks, corresponding to differences in residential crowding and early vaccine uptake.

Chicago, 1956

Overall city incidence rate: 29.2*

Whites: 13.5

Nonwhites: 108.1

Current Salk vaccine status: Vaccine previously supplied for 5 - 14 years old as of spring, supplied for 6 months - 19 years old as of early summer.

*Cases per 100,000

Baltimore, 1960 overall age 0-9

City incidence rate, age 0-9: 37.9

Whites: 33.6 (35 cases in 104,200 kids)

Nonwhites: 42.9 (38 cases in 88,502 kids)

Baltimore, 1960 unvaccinated age 0-9

Whites: 136.0 (16 cases in 11,742 kids)

Nonwhites: 119.7 (15 cases in 12,529 kids)

Baltimore, 1960 three or more Salk vaccines age 0-9

Whites: 14.9 (12 cases in 80,661 kids)

Nonwhites: 22.6 (11 cases in 48,738 kids)

So much for the modern trope on polio and race. It may be the case that Blacks were less commonly affected before WWII, or before the vaccine era — the authors of the Baltimore paper even say so, though I am not aware of any very good evidence on the claim. But, again, this would accord with lower rates in the south in general; as well as other factors which may explain such a difference.

History of the hygiene theory for polio

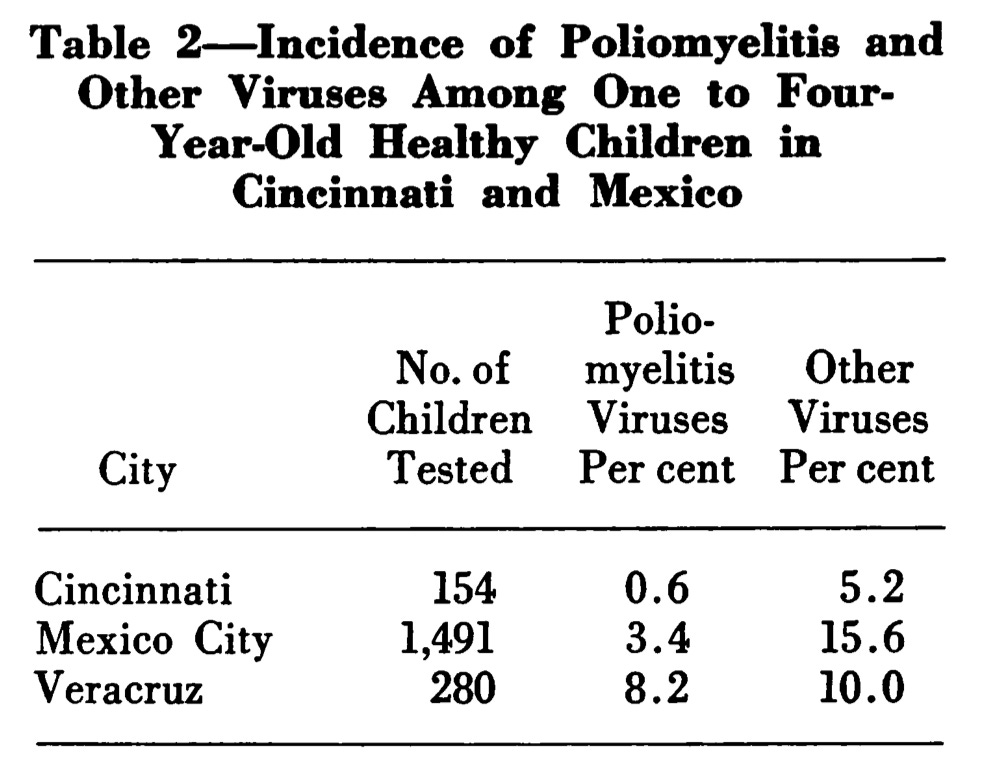

The hygiene theory for polio gains quite a bit of steam in the 1950s, when expanded efforts to look for polio antibodies in places with no paralysis epidemics consistently find polio antibodies (and later, find shed virus). In 1956, for example, Sabin used the new cell culture methods mentioned in Pt. 1 to look for polio virus in apparently healthy kids in Mexico and his adopted home of Cincinnati.4 By all appearances, polio virus was widespread among the youngest in Mexico City and Veracruz, and yet Mexico’s reported cases of paralytic polio, though increasing, were still low.

Thus, Anthony M.-M. Payne caused a stir in polio thinking in 1955 when he compared infant mortality rates to polio case rates in various countries.

And since, in the decade prior, it had also increasingly been observed that paralytic polio was affecting adults (as in the case of troops going abroad in WWII), the hygiene theory wrapped up many different observations into a tidy package: Epidemic polio was a result of a failure to encounter the virus within the first year of life, when it provides immunity either harmlessly or in a manner that results in death, which is unremarkable in regions of the world lacking in modern sanitation.

The normal course of polio, like many childhood illnesses, is probably delayed in a statistical sense by sanitation and hygiene. At least, one would intuitively think so — but disentangling such an effect from the question of crowding is difficult. Melnick and Fox, et al. observed substantial differences in how fast kids acquired polio antibodies in “upper” and “lower” households in Charleston, Phoenix,5 and Louisiana6; similar “immunity debt” was found in kids from good homes in London. But even setting aside the question of crowding in determining this difference, this still leaves several problems with the theory as far as “explaining” epidemic polio and solving the enigma.

Problems with the hygiene theory

No match to observations

Firstly, the theory fails to explain many historical observations going back to the earliest days of polio. Sanitation was the obsession of medical thought in the era when polio emerged, and so of course the issue was often addressed in early investigations of epidemics. Over and over, no clear distinction was found. Frost, et al. write of the 1916 epidemic:7

There is nothing to suggest that the spread of the disease bears any special relation to the sanitary conditions under which it occurred.

Of two areas of New Jersey which reported 94 cases in the same epidemic, they write:

Practically all of the rural houses have surface privies in poor sanitary condition. Isolation [i.e. quarantine] of cases of poliomyelitis, while attempted, was poorly performed.

Middlesex County is also a farming section. There is a considerable foreign element in the population. There are numerous villages, most of which are small, and the general sanitary conditions are poor. […] At Monmouth Junction there are huge collections of stable manure shipped from New York City. Four large piles of this manure (each about 1,000 feet in length) are found on a spur of the railroad some one-fourth of a mile west of the village of Monmouth Junction.

Filth and poverty did not prevent experiencing the 1916 epidemic, which demonstrates that it did not “sustain” exposure to the virus in such a manner beforehand as to prevent exactly the type of epidemic that never used to be observed in America before 1893. Frost, et al.’s observation touches on two problems with the hygiene theory:

“Sanitation and hygiene” were not such big transformations to life outside of cities in the 19th Century — conversely, American and European rural child and maternal mortality had never been as high as urban mortality to begin with. Urban child survival and life expectancy, in the era of “sanitation,” were merely catching up with rural areas where disease prevalence was already much lower. It was already common, for example, for rural migrants to cities in the 19th Century to contribute to urban mortality due to exposure to so many novel pathogens — they had less immunity. This had nothing to do with the “sanitation” of the American countryside; dirty farms were simply more isolated.

Also conversely, infant mortality as a “statistic” may have been increasing in America in exactly the era of polio’s emergence, due to massive immigration (as well as urbanization). Estimates for Massachusetts find that male and female infant mortality were higher in 1894 than in 1849, a finding based on imperfect statistics but consistent with intuition:

Not consistent with biology

The other problem with the hygiene theory for polio is the premise that being infected in infancy is protective against severe outcomes. If so for polio, then polio would magically be opposite of virtually every childhood illness, in which severe outcomes are most common in the youngest.

Not coherent, not good math

Finally, though there is more that could be said, the hygiene theory for polio tends not to make sense on its own grounds. If infection early is better, then why were so many children under 5 paralyzed during polio epidemics?

And why then, still, were there no epidemics in places with more rapid exposure to polio in childhood? Too avoid overly complex math and modeling, at any given age in which American children were being paralyzed due to intermittent exposure to polio, even then not all children that age were infected — many still remained unexposed and unimmune to polio, vulnerable to a later first encounter. And so, have more children in that age — despite lower immunity to go around — actually been infected for the first time vs. their more immune counterparts in the global south?

The portion of three, four, and five year-olds infected for the first time during an American polio epidemic probably would not in fact have been higher than the portion somewhere where, for example, age five is the year when kids reach 100% immunity. Again, to keep the model simple and crude:

Obviously a more exponential modeling of the rapid exposure area might make this similarity disappear; but the above model is in fact pretty consistent with vintage antibody surveys.

Thus, if exposure in ages after 1 is the problem, there still should have been epidemics even in the highest-exposure areas; as well as throughout past history in the West.

Case study and summary

Case study: Narsaq

In 1952, half of 450 residents of small shepherding and fishing settlement of Narsaq, Greenland gave blood for an antibody survey later reported by Paffenbarger and Bodian.8

Villagers in Narsaq lived in seemingly optimal “low hygiene” conditions:

Narssak is a center of fishing, canning and sheep-raising activities about 25 miles from Julianehaab, the principal town of southern Greenland. Narssak residents live under primitive conditions in crowded houses without sewerage or running water. Social life is very lively with continual visiting among households and frequent contact of most Greenlanders in the village.

Despite the lack of sanitation, the combined influence of of isolation, low population, and cold weather ensured long periods of absence for common childhood infections in Narsaq, including polio. As such, many residents of Narsaq encountered “childhood” viruses as older children and young adults. The year before the antibody survey for polio, measles had rifled through the same town in a manner typical of “virgin soil” epidemics.

Thus, the 1952 survey revealed that while type 3 polio had likely visited Narsaq in that year, type 1 and 2 had been absent in this settlement for decades:

It can be inferred that since Narsaq was “living in the past” in 1952, herding and fishing in a communal setting without running water, the past had been like the present: Residents frequently encountered polio viruses as older children and adults; the relatively high type 3 antibodies of teens suggest that they had just recently fended off the virus, whereas residents in their younger 20s were given immunity a long time ago — of course, there are other ways to interpret the results. What seems certain is that all three types of the virus frequently died out in Narsaq and awaited reintroduction for years or decades, thereupon to spread among all residents born in the meantime. And this likely had been the story of not only Narsaq, but much of northern Europe and Asia for millions of years — polio was not necessarily a “childhood” infection in the global north.

Yet epidemics did not follow. Despite such late, sporadic encounters with polio virus, occurring perhaps decade after decade in this community, no cases of paralysis had ever been recorded for this community living in the past. In Narsaq,

[T]here was no current or previous record of the disease

Thus, Narsaq combines low sanitation with regular late encounter with polio viruses. Something intrinsic or associated with early modern low sanitation, aside from regular encounter with the viruses before age 1, must be responsible for the absence of cases in Narsaq. Being “primitive” is protective, but not because it exposes newborns to polio virus in Narsaq any more frequently than it does in New York City. Again — I abuse the reader to consider a likely difference in access to medical care and injections, though this isn’t mentioned in the report.

Summary

Sanitation and hygiene are not required to disrupt the “endemic,” year-round exposure of newborns to polio virus. The global south has likely always sustained polio viruses year-round; communities in the global north have likely always experienced periodic reintroductions of the viruses infecting residents of all ages.

Something besides “being infected after infancy” is required to explain why encounters with polio virus began to result in epidemics of paralysis in the late 19th Century.

It wasn’t transportation

Obviously, a corrected model of pre-epidemic polio is needed.

Northern, rural areas have probably experienced only sporadic exposure to polio viruses throughout history, despite backward sanitation which conversely persisted in rural areas well into the epidemic era. Climate, (lack of) crowding, and transportation limitations, rather than urban sanitation efforts which were replying to mortality increases, likely exert a stronger influence on delaying prevalence and exposure to polio viruses. With the exception of transportation, none of those forces suddenly changed for rural inhabitants of Europe and America in the 19th Century.

The only hope for denying that individual susceptibility suddenly changed, therefore, would be a model in which railroad transportation suddenly made polio epidemics common, by more frequently exposing isolated people in northern climates to viruses which had not been present for long, long periods.

This, however, creates the problematic prediction that historical polio paralysis epidemics still should have been quite frequently observed. This is to say, if individual isolated communities were likely to go longer without exposure to one or multiple polio virus types in the era before railroads, then upon the rare case where a long-unknown type was reintroduced into the community — even if such reintroduction requires quite a large influx of simultaneously infected kids, which still would have happened sometimes in many places — extraordinary outbreaks of paralysis would have followed.

Polio would have been like any other observed infectious disease in this respect. Isolated, smaller islands probably did lose one or all types of polio virus in the pre-colonial era — yet outbreaks of polio paralysis never followed the arrival of European settlers in the same manner as smallpox.

We must return again to the “central clue” of the polio mystery, which is that adults at first were occasionally, but only occasionally, among the cases of the very first epidemics. This an emphatic “only” for two reasons: First, by either the standard of paralysis or “abortive” polio — which means simply a symptomatic infection resembling the flu, without any paralysis — adults in households with overt cases were less often “caught up” than children. And second, since it was later frequently estimated that polio in adults is more severe when it does happen, early cases should have been explosive in adults, unless most were already immune.

Therefore, polio was never ubiquitous in the global north, but it was not so rare, either, that rail transportation could have so drastically changed the prevailing rate of encounter to new strains (i.e., to “sometimes happened” from a prior “never happened”).

The best model for “pre-epidemic polio,” thus, is likely that the virus tended to visit rural and urban habitats as frequently as “epidemic polio” — at least before WWII and widespread automobile transportation. Seasonal, sporadic polio virus infection in all ages and all places simply went unnoticed throughout all of history before 1883, because humans were not yet as susceptible to paralysis. (Infection in children would likely have been taken for “summer complaint” or “summer diarrhea,” which in fact was sometimes associated with paralysis of the same transient type that follows diphtheria — but which likely had many causes, especially bacteria in the era of poor rural sanitation.)

It wasn’t imagination / over-reporting

The ultimate skeptical interpretation of the polio problem is that it was simply a phenomenon of noticing something that had always taken place.

Perhaps the priming condition for this noticing was the formation of large, semi-unified public health bureaucracies with efficient paperwork, capable of discerning patterns in rare outcomes — this was indeed a novelty of the 19th Century. Such noticing would then “trigger” even more noticing — polio became elevated to a reportable illness in various public health regimes after 1900, resulting in increased case counts; this was followed by media and medical hysteria and over-treatment (addressed below); the whole thing in other words was a panic over normalcy.

This is nearly a convenient fit for the problem. Public health itself was a managerial response to industrial, urban problems of disease and class disparity — it sought to manage urban populations by monitoring them. The failure of the skeptical theory however rests on the “nearly” — enough progress was made in reporting infectious disease before 1893 that polio epidemics already would have been noticed if they were widespread. In other words, the erection of public health bureaucracies was timed in such a way that the last years before the “switch” to epidemic polio were reliably captured and characterized (as in, as being epidemic-free), despite the lack of awareness of the disease. For example, the British Public Health Acts of 1872 and 1875 substantially expanded and consolidated public health powers, the notification of diseases, and the establishment of isolation hospitals. Yet no polio epidemics were noticed in these years — because polio epidemics did not yet exist.

Further, the transition of epidemic polio paralysis from a strictly Western, and mostly childhood disease to one affecting other settlements and greater numbers of adults (and that latter transition probably was due to hygiene), in the mid-20th Century, refutes the idea that there was nothing “new” to polio. Once the “switch” from an invisible, rare disease to one occurring in epidemic waves takes place in these two new populations, islands and young adults traveling abroad, it disproves that the same “switch” in Western children was imaginary. We may examine the case of soldiers.

Case study: The “switch” in soldiers abroad

Likewise, the extraordinary observation of epidemic paralysis in British, American, and Kiwi troops heading to the Middle East during WWII refutes the idea that there was nothing truly new about polio. Troops setting foot where polio virus was far more common than at home, resulting in sporadic and rare childhood paralysis without epidemics, often encountered the virus for the first time. In the instance of Egypt, 74 and 32 British soldiers came down with polio in 1941 and 1942, respectively. The next year, 1 out of every 2,350 American soldiers in the Middle East experienced the same disease.

Instances of armies and colonial expeditions bringing large numbers of previously polio-uninfected men into contact with polio virus would have happened since ancient times; for Europeans, it would have been a constant feature of the colonial era, as well as WWI. But unlike other diseases which past experience or contemporary biowarfare rumors had conditioned the US Army to prepare for in WWII — influenza, yellow fever, etc. — there was no expectation that adult soldiers going abroad would experience polio.

The “switch” — placing large numbers of polio-naive men into contact with the virus results in a surge of paralytic cases in 1941, but not 1914 — again cannot be merely because this was the first time ever that substantial numbers of European military personnel hopping the globe were not immune, “because hygiene.” Nor was this switch due to improved practices in public health monitoring or anxiety over infectious disease in Britain, as the most substantial developments in this regard were largely all in place before WWI. Something else had changed. Again, I abuse the reader to consider the much more substantial use of prophylactic injections, in preparing for other foreign diseases during WWII, in rendering soldiers susceptible to previously un-encountered polio viruses. This change was particularly stark in Britain, where little effort had been made to vaccinate the public against diphtheria before 1940.9

Was it all medical intervention?

The priest answered low:

“It seems as though her back were badly hurt, Ragnfrid; I see no better way than to leave all in God’s hands and St. Olav’s—much there is not that I can do.”

It was eventually discovered and understood that all manner of medical treatment (and diagnosis) of polio infection likely increased the incidence of paralysis. Everything that could “bother” the patient suspected of infection, i.e. every weapon of “care” wielded by the physician, might make paralysis more likely to occur and less likely to heal. Thus Paul writes in 1941,

But the reason we do so little in the early stage is to avoid the possibility of harmful procedures. Clinical judgement (and we have no statistics to prove this) indicates that trauma of almost any kind may often turn a case in the wrong direction. Among traumatic procedures, I would include: unnecessary vena punctures or lumbar punctures; the administration of strong purgatives; the injection of foreign protein […]

The point is, that when a child’s fate is hanging in the balance as to whether the virus is going to damage the central nervous system severely or not, it seems better to do nothing, rather than to do something which may not only be of unproven value, but also may fall under the category of a traumatic procedure. In support of this thesis, the best series of cases on record, that is the series with the lowest mortality and the lowest incidence of paralysis, received nothing but bed rest.10

Therefore it is certain that the reaction to polio epidemics increased the scope of harm of the same phenomenon. The most aggressively-managed epidemic, in 1916 in New York City, claimed for all time the American record for polio-related deaths. Every intervention under the umbrella of polio diagnosis and “treatment” — from spinal taps to injections — likely exacerbated outcomes in this year, especially in infants.

But the harm of reaction to polio is still not sufficient to explain the emergence of the same epidemics which were being reacted to. Throughout the polio era — aside from 1916, New York — case record after case record describes individuals who attempted to “shrug off” the problem, only to wind up with severe paralysis. The paratrooper who hauled machine guns up a hill on his second day of illness was not alone — in the same case series:11

A schoolboy aged 16. […] Day 4: The symptoms continued, but after lunch he developed a severe headache. He played tennis for half an hour, and that evening reported sick for the first time. He was put to bed, sleepless and restless. During the night severe paralysis developed in his trunk and lower limbs, and his arms also became weak. He kept moving his legs till they would move no longer, and developed retention of urine.

On the ninth day his breathing became difficult and he was put in a respirator for three days. Four months later there was still gross paralysis of his trunk and thighs.

Thus, even if aggressive treatment likely exacerbated polio paralysis outcomes, the high rate of permanent harm in the polio era — vs. the era when childhood paralysis was not medically interfered with — is not adequately explained by post-infection treatment alone. Treatment likely made epidemics much worse; but they still would have been novel, distinct, in scale regardless.

If you derived value from this post, please drop a few coins in your fact-barista’s tip jar.

Andersen, NSB. et al. “Host Genetics, Innate Immune Responses, and Cellular Death Pathways in Poliomyelitis Patients.” Front Microbiol. 2019; 10: 1495.

Bundesen, HN et al. “Preliminary report and observations on the 1956 poliomyelitis outbreak in Chicago; with an evaluation of the large-scale use of Salk vaccine, particularly in the face of a sharply rising incidence.” J Am Med Assoc. 1957 Apr 27;163(17):1604-19. doi: 10.1001/jama.1957.82970520003013.

Gresham, GE et al. “Epidemic of type 3 paralytic poliomyelitis in Baltimore, Maryland, 1960.” Public Health Rep (1896). 1962 Apr; 77(4): 349–355.

Ramos-Alvarez, M. Sabin, AB. “Intestinal Viral Flora of Healthy Children Demonstrable by Monkey Kidney Tissue Culture.” Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1956 Mar; 46(3): 295–299.

Melnick, JL. Walton, M. Isacson, P. Cardwell, W. “Environmental studies of endemic enteric virus infections. I. Community seroimmune patterns and poliovirus infection rates.” Am J Hyg. 1957 Jan;65(1):1-28. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a119852.

Fox, JP. Gelfan, HM. LeBlanc, DR. Conwell, DP. “A Continuing Study of the Acquisition of Natural Immunity to Poliomyelitis in Representative Louisiana Households.” Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1956 Mar; 46(3): 283–294.

Lavinder, CH. Freeman, AW. Frost, WH. “Epidemiologic Studies of Poliomyelitis in New York City and the Northeastern United States During the Year 1916.” Available at https://www.google.com/books/edition/Epidemiologic_Studies_of_Poliomyelitis_i/_-YRAAAAYAAJ

Paffenbarger Jr, RS. Bodian, D. “Poliomyelitis immune status in ecologically diverse populations, in relation to virus spread, clinical incidence, and virus disappearance.” Am J Hyg. 1961 Nov:74:311-25. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a120222.

For British soldiers I do not have an exhaustive list; but all English youth 5-15 at the time would have been targeted by the wartime diphtheria immunization campaigns of 1941 and 1942-1943. Inferred dates of vaccination for teens sampled by Bousfield in 1945 imply that a good deal of teens were injected two to three years prior to the national campaign. Whereas before 1939, British diphtheria vaccination rates were low. This wholesale embrace of the diphtheria vaccine (toxoid) in early 1941 would have been sufficient to result in a few injected soldiers of all ages; and obviously soldiers may have been subjected to additional preparations for deployment abroad as they were in the US and Germany (typhoid vaccine for troops in the east). Sparse citations here; I will further review the British and Canadian situations later.

Paul, JR. “Poliomyelitis.” Bull NY Acad Med. 1941 Apr; 17(4): 259–267.

Russel, WR. “Poliomyelitis; the pre-paralytic stage, and the effect of physical activity on the severity of paralysis.” Br Med J. 1947 Dec 27; 2(4538): 1023–1028.

I think that I like your theory Brian. Injection is a method to bypass the natural defenses. Normally anything that enters our body has to deal with the skin, the digestive system, or the mucosa. Anything that enters the body is sort of naturally quarantined to places that are accessible from the route of entry.

This btw is why I am not so concerned with the mRNA being injected in cows controversy. Obviously, I am not in favor of it but if it gets cooked, and chewed, and acided and biled, etc. etc. its potential to do harm is dramatically decreased. The needle is a big mistake. It is medicine that works against the body and against nature not for it. All of the children crying and screaming about shots should have been a clue a long time ago, we are born knowing that that is not a valid route of entry.

https://hiddencomplexity.substack.com/p/skyrocketing-newborn-syphilis-and?publication_id=597993&utm_campaign=email-post-title&r=h1ah5

This was my next email I opened up, so now I’m thinking maybe polio virus got a vampire virus that increased its potential for paralysis!